WHITE ROCK, SD — As a senior in high school in 1969, Steve Johnson was a little bit of everything. He was a student and played wide receiver on the nearby Rosholt High �������� football team. He helped embalm corpses at the local funeral home and drove ambulances. He worked the family furniture store business and he listened when a hysterical woman came in the day after Halloween.

“I was in the furniture store and we were unloading La-Z-Boys and this woman came in and she was really wound up. She said somebody dug up a grave at the cemetery. My dad said she was nuts, and I told him we better go out there anyway,” Johnson told Forum News Service in a recent interview.

ADVERTISEMENT

The sight at Lake View Cemetery was true, and gruesome.

“We went out there and sure enough the grave was dug up, it was Halloween night they did this, and we called the sheriff and coroner. We buried this man. His name was Warner Wilson. He was a farmer and an old bachelor,” Johnson said.

“Usually, we buried people in cement vaults, but that was a wooden vault we used to bury him,” said Johnson. As he stood over the grave, he realized the culprits had to be close to home.

“Somebody had to have been at that funeral to know. They smashed that crate and took the head off,” Johnson said.

Johnson knew Wilson, a humble, elderly farmer and lifelong bachelor.

“We had buried him a couple years earlier, and this bothered me. The sheriff came out and the coroner, we took the body back to the funeral home in a body bag to try and find the head,” Johnson said.

White Rock

Wilson was born to Swedish immigrants, Swan and Hannah Wilson, in 1901, according to the U.S. Immigration records. Their ship was the same ocean liner terror to American shores, but was turned away. Many of those on board were later sent to concentration camps, according to the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

ADVERTISEMENT

A farmer, like his father before him, Wilson was 57 when signed up for the draft during World War II. By the 1950s, his younger brother, Ben, lived with him on the family farm passed down from his parents, and subsequent immigration records noted that they reported their birthplaces as Minnesota.

The township of White Rock, once a bustling frontier village along the Bois de Sioux River, which defines part of the border between Minnesota and both South Dakota and North Dakota. The town was named after a near the Fargo line of the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway.

Founded by Swedish settlers in 1884, it once had about 600 people who built churches, saloons, banks, stores and schools. When the railway moved, the businesses left.

By 1969, the year Wilson’s grave was unearthed, White Rock was nearly a ghost town. One watering hole, named Helen's Bar, was still open, and on the weekends it was a magnet for teenagers who hit the 18-year-old milestone from Minnesota and North Dakota, where the drinking age was 21.

“On certain nights of the week, two or three towns would meet in White Rock, and there were no police around. There could be 1,000 kids on the weekend there, they would come across the border to drink,” Johnson said.

The investigation

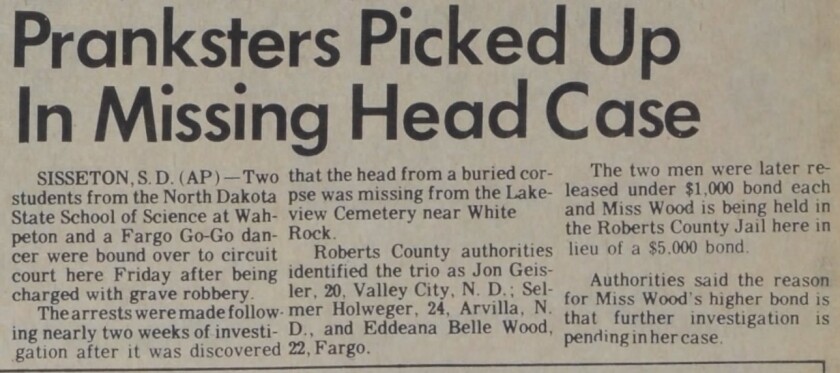

The Roberts County Sheriff’s Office told Forum News Service that they no longer had the case file on the grave robbing incident. The investigating officers, who have since died, spent two weeks investigating the incident, according to news reports in 1970.

ADVERTISEMENT

Johnson remembered that one of the suspects was struck by a guilty conscience and confessed. Two students from the North Dakota �������� of Science at Wahpeton, North Dakota, were given LSD or mind-altering drugs by a female nightclub entertainer who worked in Fargo, North Dakota, Johnson said.

“One of the boys, it was probably his conscience that got to him, came down off the acid, and he must have told somebody where the head was. It was out on a farm in an old shed,” Johnson said.

News reports at the time made no mention of why the head was taken, but Johnson said the crime was committed for a satanic ritual.

“She was a witch, she was into devil worship. She wanted that head for rituals. Those poor kids ... were stupid," Johnson said. "I’m sure she was cute. She found a couple kids, and I think their testosterone was going pretty well."

The two-week investigation started in a Wahpeton nightclub “first as a heckling of the girl’s act and then as a dare that magnified into a bizarre action,” Police arrested Eddeana Belle Wood, 22, Colorado Springs, Colorado, the Fargo night club entertainer better known as “Dusty” Wood; along with two college students.

All three were charged with “wanton and malicious removal of part or all of a dead body,” according to the Grand Forks Herald.

The trio were sentenced in South Dakota to serve two years probation and ordered to repay $1,090 in costs for their grave robbery.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The three admitted entering a rural White Rock, SD, cemetery in the early morning hours last Oct. 30 and opening the grave of a man buried there. The head of the corpse was recovered several days later at a vacant farm near Breckenridge, Minn.,” The Forum reported on June 12, 1970.

The head of the corpse was about 80 years old, according to The Forum. the attention of a passing farmer. “No attempt had been made to cover the coffin,” The Forum reported.

After their arrests, they all had to pay $2.50 per day for room and board while at the Roberts County Jail in South Dakota.

“It was sad. That poor man was very humble," Johnson said. "I knew him. And to have that happen is just sad."

Johnson continued: “Everybody knew what happened, and I don’t think they knew what to do with these guys. It sounds far-fetched, but that’s what drugs will do to people.”

Three years later

Wood was in Fargo in October 1972, according to The Forum.

ADVERTISEMENT

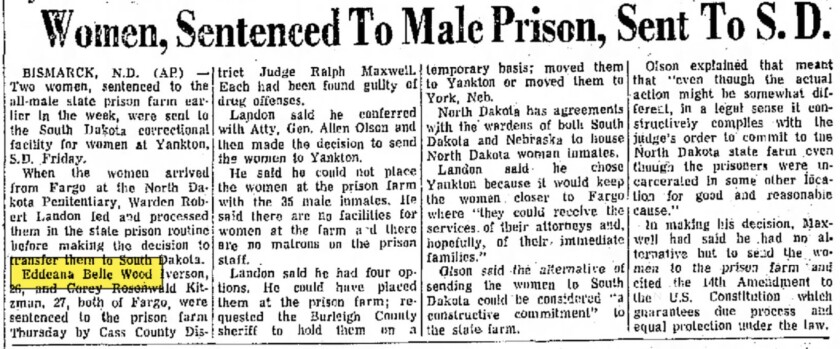

Wood, whose last name had become Iverson, was caught selling amphetamine tablets, and was sentenced to one year in jail.

She spent part of her after Judge Ralph Maxwell sentenced her to the all-male North Dakota State Farm in Bismarck, North Dakota, a place where those found guilty of misdemeanors would sometimes go and work. The farm was renamed the Missouri River Correctional Center in 1991, according to the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Before she could get settled in on the 45-man dormitory — which had no separate services for women — Robert Landon, the warden at the North Dakota State Penitentiary, in Yankton, South Dakota.

Not long after, Landon had to answer for his decision to Maxwell in court, and said if he had the chance to change his decision, he still would have sent them away, according to multiple newspaper reports in March 1973.