SIOUX FALLS, SD — For nearly half a century, Catherine Van Horn kept a secret that she divulged only on her death bed.

In 1880, she killed her mother, Mary Egan, and blamed the deed on her stepfather, Thomas Egan, who was hanged three times until he was dead after a Dakota Territory jury found him guilty. She got into an argument with her mother around Sept. 14, 1880, beat her with a picket pin — a hardwood stake used to tether a horse — and strangled her with a rope before dumping her body into the root cellar.

ADVERTISEMENT

Van Horn’s confession — which more recent reports established was in 1926 — received little publicity. Newspaper articles in 1900, however, reported that Van Horn, while on her death bed in Washington, wrote a letter confessing to doctors there that she committed the crime.

“The confession is given little credence by those who remember the facts in connection with the crime,” the Argus Leader reported on Jan. 19, 1900. “Suspicion pointed to the husband, and he was arrested the same day. While the evidence was all circumstantial, it was considered very strong and Egan was convicted and hanged.”

The victim: Mary Egan, widowed before meeting her second husband, had one daughter from her previous marriage named Catherine, who was 5 when she remarried. She moved to the Dakota Territory with her new husband around 1866, and they had three sons together.

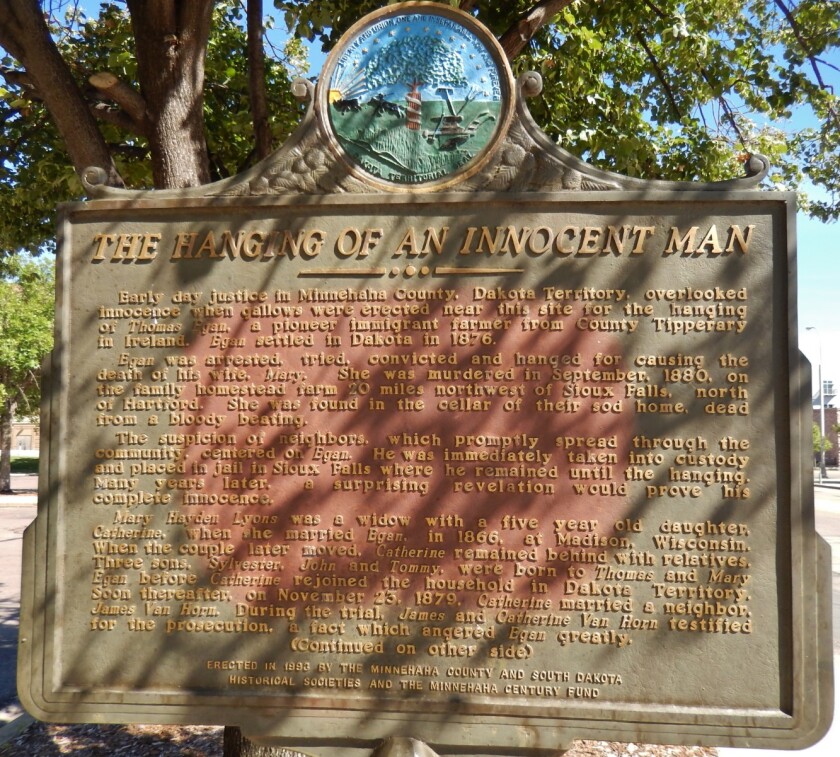

The suspect: Thomas Egan, a native of Tipperary, Ireland, a pioneer farmer who traveled from Wisconsin to the Dakota Territory. He was a man of few words and his wife’s murder was pinned on him. He “claimed his innocence until the very last,” the Black Hills Weekly Journal reported. Sheriff Joseph Dickson of Canton, Dakota Territories, didn’t hang the condemned man once, or twice, but three times before he was pronounced dead on July 13, 1882.

The circumstances: the Egans lived about 18 miles northeast of Sioux Falls, and on Sept. 14, 1880, Egan went out to cultivate crops with two of his sons. He left the boys at some point and went home, found his wife dead, beaten and strangled with a rope. During the trial, the prosecuting attorneys alleged that was when the murder occurred.

The real killer: Catherine Van Horn, Mary’s daughter, got into an argument with her mother and beat her, then strangled her to death. She then blamed the murder on her stepfather, testified against him at trial, and lived with the dark secret until her death.

ADVERTISEMENT

A written confession

A century after Thomas was hanged, his great-grandson, John Egan, a journalist and sports editor with the Argus Leader, described as a “master chronicler” in his obituary, received a letter, written by Van Horn, from a cousin.

All his life his great-grandfather was the black sheep nobody knew anything about. The name — Thomas Egan — rarely came up, and if it did, nobody wanted to talk about him, John wrote in 1993.

published a story on Thomas reporting that he often beat his wife, and on the day she was killed, he sent his children away and murdered her.

But the letter John held in his hands was her confession. His great-grandfather was innocent, he wrote.

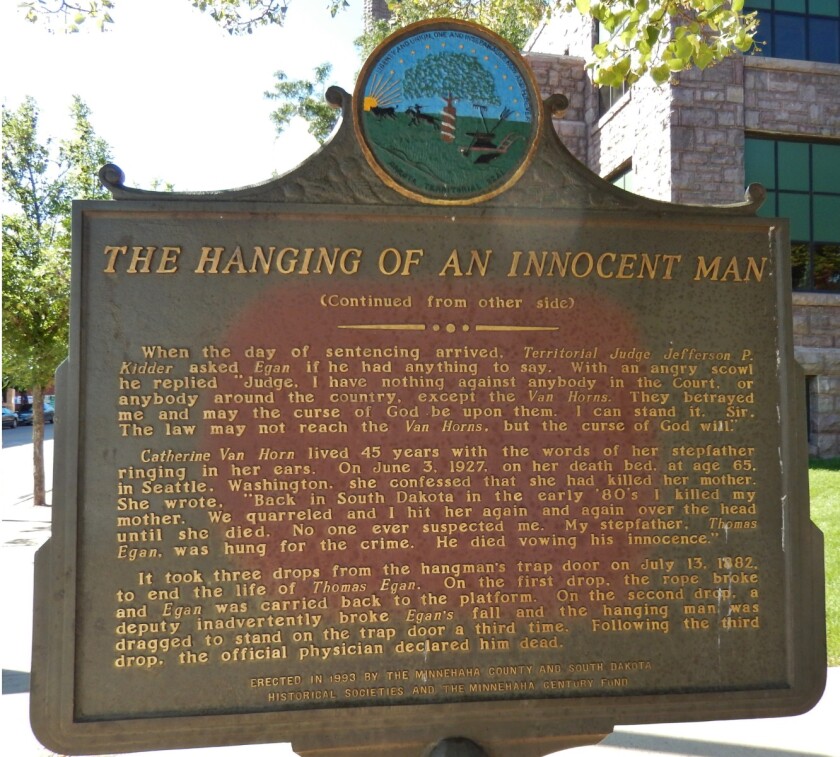

“Back in South Dakota in the early ‘80s I killed my mother,” Van Horn reportedly wrote. “We quarreled and I hit her again and again over the head until she died. No one ever suspected me. My stepfather, Thomas Egan, was hanged for the crime. He died vowing his innocence.”

Newspapers in the 1880s chronicled his great-grandfather’s hanging, the death of his great-grandmother, the awkward trial, the undue punishment, in detail. But Van Horn’s confession years later went unnoticed or ignored, he wrote. Growing up, nobody mentioned his ancestor’s innocence.

He investigated. In the 1980s, he wrote a series of articles about his search, declaring in 1986 that: “Thomas Egan, an innocent man, died at the end of a hangman’s rope 104 years ago today … He is my great-grandfather.”

ADVERTISEMENT

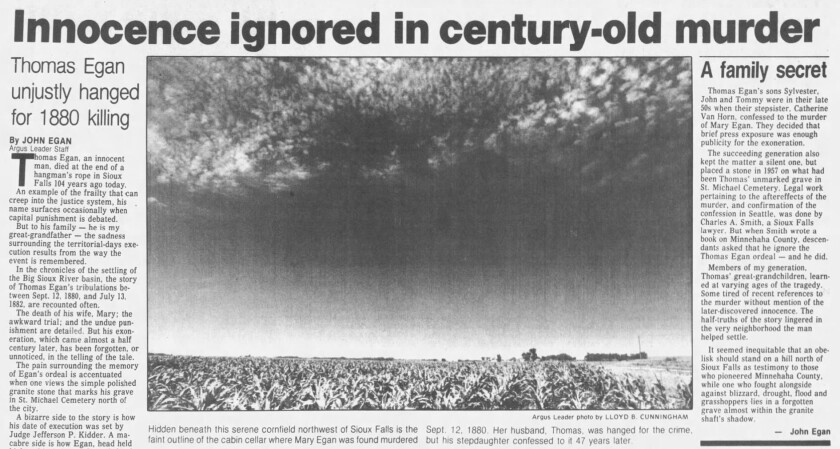

The farmhouse where Mary was killed is “now merely an indentation in cornstalk-covered earth. It is a tranquil place, made mysteriously foreboding only by the knowledge of what happened there almost 106 years ago,” the Argus Leader reported in 1986.

“The silence is much like that of a hooded Thomas Egan as he stood on the downtown Sioux Falls gallows, not knowing who killed his wife. And the only person who did wasn’t talking,” the Argus Leader reported.

By 1993, John wrote a book about his great-grandfather ”

‘Where is ma?’

At about 9:40 a.m. on July 13, 1882, two years after a jury found him guilty of a crime he didn’t commit, Thomas walked from the county jail toward the gallows in what is now Main Street in downtown Sioux Falls.

Egan slept soundly the night before, and he had eaten a hearty breakfast before the death warrant was read to him.

The newspapers called him “horrid” and “diabolical.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The “kind and noble” Judge Jefferson P. Kidder, who sentenced Thomas, labeled him “brutal” and “inhuman.”

Every newspaper story from the 1880s that Forum News Service discovered linked hearsay to unverified facts and reported that Thomas was a murderer with a murderous past.

“The trial completed the picture; the bloody rope and stake with the hair of the victim still clinging as unanswerable evidence, the pants, vest and shirt of the defendant worn on the morning of the murder, red with gore … and the truthful narratives of little Tommy and Jonny as to their father’s actions and cowering, trembling evasion when asked ‘Where is ma?’” on December 15, 1881.

His final words were to say “No,” when Dixon asked if he had anything to say. He had already spoken his mind.

Thomas said on May 30, 1882: “I have no words to say against anyone about this court, nor anyone else except the Van Horns, George Hill and Sydney Healey. They have betrayed me, and I pronounce the curse of God upon them,” he said, according to the Yankton Press and Dakotan.

“Egan marched stolidly up the trap and without a quiver stood fearlessly awaiting the black cap, which was at once adjusted by Sheriff Dixon,” the Yankton newspaper reported on July 13, 1882.

Dixon slipped the $9 silk rope around his neck. The sheriff had tested the rope with a 185-pound sand bag, and Egan weighed 175 pounds.

ADVERTISEMENT

And then he sprung the hangman’s trap.

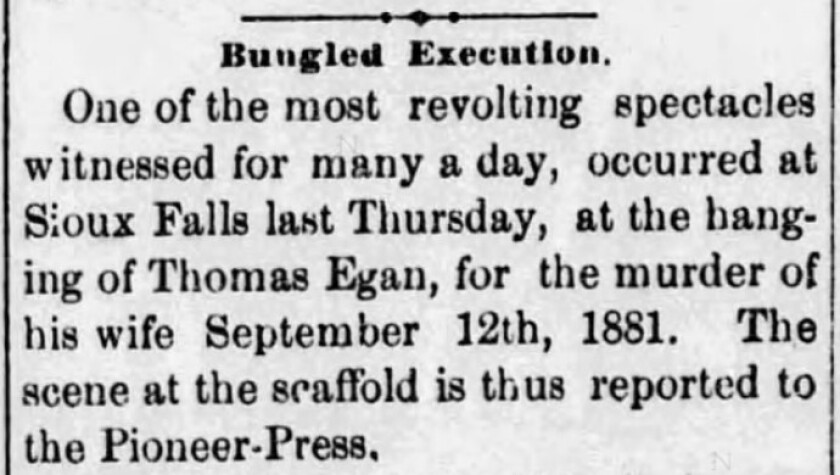

“The body shot down through the opening, but to the horror of all beholders the rope broke, and the body struck the ground with a heavy and sickening thud. Exclamations of horror broke from the crowd of spectators at the awful sight. The attendants quickly picked him up, and uttering fearful groans, he was carried up the platform,” the Union County Courier reported.

Two minutes later a new silk rope was placed around his neck. “This time one of the attendants had hold of the rope, and instead of letting go, hung on to it and let the body down gradually, notwithstanding the cries of ‘Let go!’ from the spectators,” the Union County Courier reported.

Egan failed to die a second time, so attendees brought him up once more and Dixon sprung the trap a third time after ordering everyone to stand back. Egan dropped five-and-a-half feet and died.

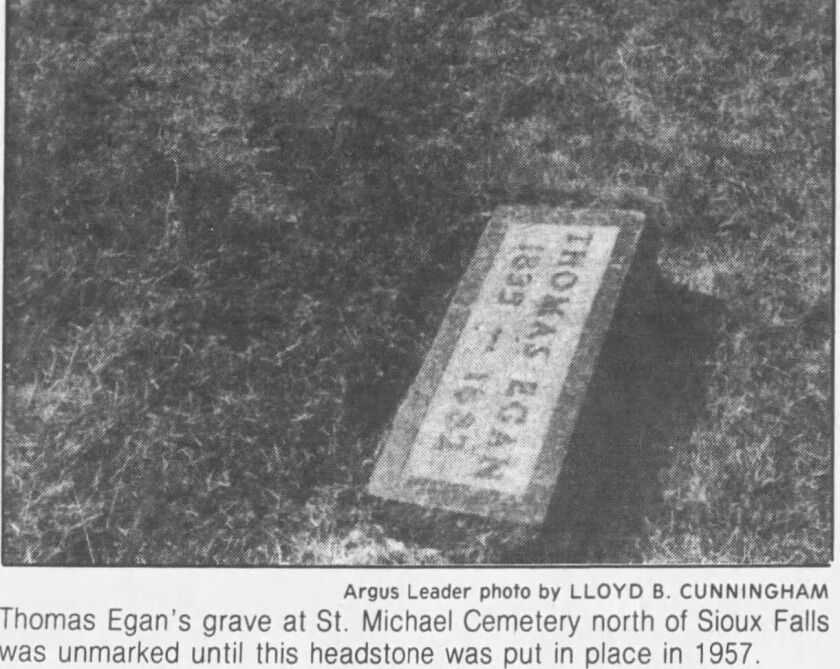

Two doctors checked his pulse and pronounced him dead eight-and-a-half minutes later. The coffin was brought in, his body cut down, and he was placed in his final resting place at 10 a.m.

Vindication

John researched and wrote about his great-grandfather for nearly a decade before the truth became accepted. After publishing his book, the Minnehaha County Historical Society stepped in to help, and in 1993 erected a plaque declaring his great-grandfather’s innocence at Sixth Street and Main Avenue, the spot where he was hanged.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I wanted to clarify within our family with enough information, so that succeeding generations wouldn’t have half truths like my generation did. The original driving thing was to do it for my grandchildren, but then it became more than that,” John was quoted in an Aug. 16, 1993 story.

John, who died in 2017 at age 86 in Sun City, Arizona, wrote for the Argus Leader for 34 years. Before his death in 2002, he Hall of Fame.