WILTON, N.D. — It was cold that day at the Casino Coal Mine.

had been told a dead body had been found 200 feet down the mine angled into lignite coal beds of central North Dakota in late March 1899.

ADVERTISEMENT

Sure enough, there it was. Frozen solid. The coroner went through the corpse’s pockets and found a bunch of keys and about $3 in cash.

But there was troublingly clear evidence this was a murder. There was a gash across the man’s face, and as an examination would prove later,

The man appeared to have been There was little blood around the corpse. His clothes were pulled over his body, and there were marks on his ankle where a strap had been tied, the better to pull him down the mine shaft.

The man’s name was August “Gust” Stark. He had been a worker at the mine, and was known to have some money.

The Casino mine was owned by a father and son, James Jenkins and Ira Jenkins, who had reported Stark missing. White and State’s Attorney Ed Allen decided to investigate further, and their first questions were for the Jenkinses.

What would follow would be one of the more extraordinary murder cases in North Dakota’s early history, resulting in one of its few executions and a surprise exoneration, all due to a piece of paper discovered in a dead man’s pocket.

The investigation

The two Jenkins, father and son, initially claimed to have no knowledge of Stark’s murder. But, after telling confused and sometimes contradictory stories, they quickly turned on one another and accused each other of the crime.

ADVERTISEMENT

The two were put in separate cells, and

James, the father, his son Ira had wanted to buy a piece of land from Stark, who refused to sell. James returned home the evening of March 16, 1900, only to be met by Ira, who told his father he had killed Stark in the house, then dragged his body outside.

Later, White visited the house and found evidence — bloody carpet and a door — that seemed to bear out this part of the confession.

Before going to the authorities, James said he and his son concocted a made-up story about finding a missing Stark. But now, under pressure, James had decided he needed to tell the truth.

“Ira Jenkins was in court and faced his father, while the latter gave testimony that was to fasten the crime of murder on his son,” the Bismarck Tribune reported.

Ira, the son, In his version, he had been absent from the house and returned to find his father choking Stark, then laying him across a chair and shooting him in the head.

The authorities weren’t convinced by this claim. Not only was there no sign that Stark had been strangled, but he was also much bigger and stronger than the elder Jenkins.

ADVERTISEMENT

The jury also wasn’t convinced when Ira Jenkins alone was brought to trial, even though his father was still technically charged with the same crime.

After seven hours of deliberation, the jury found Ira Jenkins guilty of Stark’s murder, primarily on the strength of his father’s testimony against him. Judge Walter Winchester on Sept. 14, 1900.

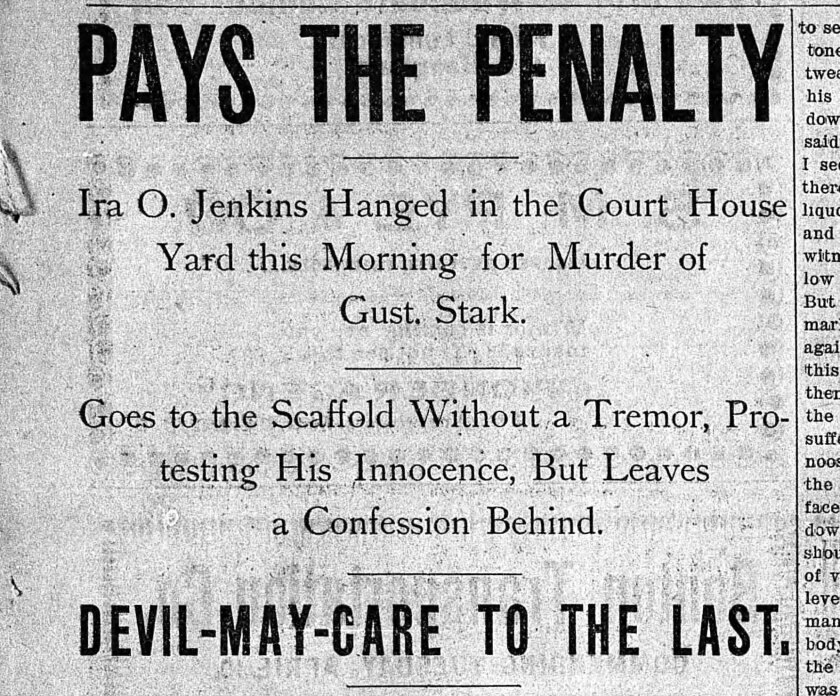

The execution

The pending execution merited newspaper coverage across the state and elsewhere in the country.

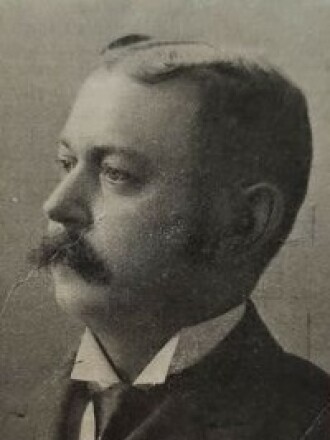

All of Ira Jenkins’ legal appeals failed. In June, his wife, all of 16 years old but who went unnamed in press reports, in Bismarck asking Gov. Frederick Fancher to commute Jenkins’ death sentence, on the grounds that his conviction was largely due to testimony by his father, who was also charged with the crime.

In September, Fancher He said the evidence didn’t justify him interfering in the matter. Jenkins was set to be executed two weeks later. On the eve of the execution, a 90-day reprieve request was turned down by Lt. Gov. Joseph Devine.

Jenkins was now out of options. A scaffold was erected in the Burleigh County courthouse yard in Bismarck, with a foot-operated trap that would drop him to his death.

ADVERTISEMENT

The with a drizzly rain and a thunderstorm dampening and delaying the affair. Just after 8 a.m., Ira Jenkins was marched to the scaffold, a cigar clutched between his lips.

Reportedly, he had been cussing and swearing since he was fed ham and eggs for breakfast at 4 a.m., and didn’t quit even as he stepped onto the scaffold platform. This “stamped him as a remarkable example of depravity and villainy,” the Bismarck Tribune wrote.

His father, James, was there. Ira shook his hands and bade him goodbye. He then whispered a word of advice to the county sheriff before addressing the crowd.

He blamed liquor for “this” and launched into a tirade at his lawyer, before finishing with, “I am an innocent man.”

He was hanged until dead.

The sheriff, on Ira’s advice, checked the deceased man’s pockets. that read, “Please clear the old man for I take all the guilt on myself.”

Jenkins left behind a young wife and an infant child, as well as an exonerated father.

ADVERTISEMENT

The murder charge against James Jenkins was dismissed.

Note: This article is based on contemporaneous coverage from North Dakota’s newspapers including The Bismarck Tribune, The Hope Pioneer, The Fargo Forum and Daily Republican, The Jamestown Weekly Alert and The Washburn Leader.