BEMIDJI, Minn. — Western outlaw legends like Jesse James or Butch Cassidy fueled novels known as and blockbuster Hollywood movies, but their stories pale in comparison to the real lives of lumberjack sky pilots and roughnecks of the Great North Woods in Minnesota.

In the early 1900s, the town of Bemidji, Minnesota, had about 5,000 residents. Tucked into pine forests along the north bank of the Mississippi River, it also boasted about 48 saloons, 28 gambling dens and five large brothels, according to newspaper reports at the time.

ADVERTISEMENT

Not far away in the forest lived about 20,000 lumberjacks, choppers, loggers and rivermen, and Bemidji depended on those hardened men to survive long enough to pour their hard-earned cash into the town’s businesses.

“Bemidji lived off those lumberjacks, and it reaped its living by deliberately making them drunk, luring them into gambling or into vice and willing the money away from them,” the Evening Journal reported in a story about lumberjacks in 1913.

When the money didn’t come in fast enough, townsfolk drugged their drinks, sometimes “blackjacked” or beat them senseless, according to the Evening Journal.

One man, Francis E. Higgins, took notice. He was a “dapper-appearing person, wearing a linen shirt and white stand-up collar,” the Evening Journal reported. As a pastor of the Presbyterian church — capable of throwing a solid right hook —the lumberjacks became his turf. He picked up a heavy backpack, his snowshoes, and trekked into the “great forests” to find them.

They called him a "lumberjack sky pilot" because he chose to live with the lumberjacks — in the forests of the Midwest, stretching from New York to Canada to Minnesota — and because men like Higgins piloted “souls to the sky,” according to the Minnesota Historical Society.

‘Hades would break loose somewhere’

In the late 1800s to early 20th century, logging camps were rough places, where fugitives hid to avoid capture by the law. that many of the camps were also haunted by a headless ghost.

ADVERTISEMENT

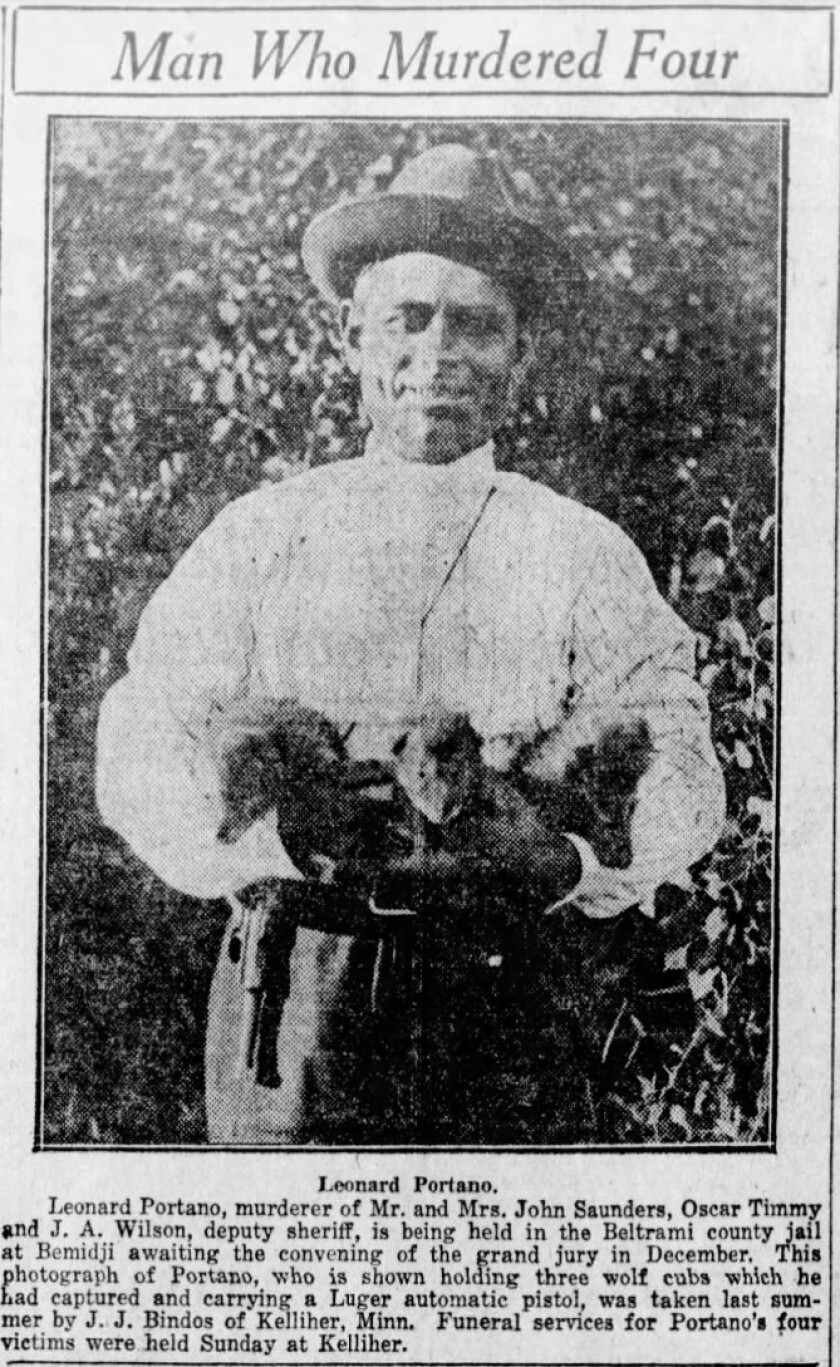

In 1923, 35-year-old after being rebuffed by a woman he swore was promised to him in Kelliher, Minnesota, according to the Minneapolis Star.

Myrtle Sanders, the sister of Portano’s brother’s wife, had a local suitor, named Oscar Timmey. She told him she wanted nothing to do with Portano. An honest and likable farmer, Timmey talked to Sanders’ parents, who agreed, and he decided to “explain diplomatically to Portano that neither Miss Sanders nor her parents desired him to pay attention to her,” the Minneapolis Star reported.

“The badman whipped out a revolver and shot Timmey through the shoulder… boldly stalked up to the Sanders home and demanded to see Myrtle,” the Minneapolis Star reported.

Myrtle had no choice but to comply, and when her 60-year-old mother gave chase, he shot her in the chest. He then dragged Myrtle and forced her father into his cabin, where at close range he decapitated the father, John Sanders, after pulling both triggers of a shotgun.

But Portano’s body count was just beginning. “Crazed by jealousy and drunk with moonshine,” Portano hunted down Timmey — who had survived the first attack — reported.

Dragging Myrtle to the roadside, he forced her to hide in bushes while he waited, “toying with his trigger” on a rifle. Soon enough, J.A. Wilson, the village marshal and deputy sheriff, came driving down the highway in an automobile. Portano shot him at long range, killing him before he could get out of his car.

Only when the area was deserted of people did Portano turn his attention back to Myrtle.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Dragging the half-fainting girl back to his cabin he subjected her to a fiendish assault. Then, while she lay moaning with pain and grief, he coolly sat down at his table and with unbelievable bravado wrote a note telling of his bloody deeds and warning pursuers that they could expect a fate similar to that of his victims,” the Minneapolis Star reported.

When Myrtle woke after passing out, Portano was gone. So were his guns and ammunition.

“He had taken flight, armed to the teeth and resolved to fight to the death,” the Minneapolis Star reported.

“The killer… who carved four notches on his gun within a few hours yesterday, is believed to have been responsible for seven murders. His pursuers, most of them woodsmen and dead shots themselves, will take no chances with him. If he is brought to bay, a battle to the death will doubtless result,” the Minneapolis Star reported on November 16, 1923.

The next day, Portano was caught while snoozing in a haystack. Sheriff Julius R. Johnson captured him before the woodsmen posse became a lynching mob. When the posse found out Portano had been captured, they attempted to take the law into their own hands and chopped a telephone pole down on the road leading into Kelliher.

But the deputies “swung the car to one side of the road, skirting the end of the pole and dashed on down the road with unlessened speed,” the Duluth News Tribune reported.

While awaiting trial, Portano attempted to escape the Beltrami County Jail by using an iron rod he tore off his bunk bed to bust through the cell window. A jail janitor alerted Johnson, who stopped Portano’s escape, the Minneapolis Journal reported on December 11, 1923.

ADVERTISEMENT

Portano was charged with murder, among other crimes, and sentenced to life imprisonment at the state penitentiary at Stillwater, Minnesota.

Later news reports revealed that Portano was also wanted for murder in New York, and fled to Minnesota to hide.

“The lumberjack was the bete noir of the copper. When the big fellows blew in with mits like boxing gloves, with ponderous weight behind them, we all felt that hades would break loose somewhere,” in 1924.

‘Blood was a man’s passport’

Another lumberjack with a lurid past was John Sornberger, a more than 200 fights in bar room ring battles. He went by many names when he was young. To some, he was Jack McWilliams, a criminal wanted by every sheriff in Minnesota. To others, he was “Pug” Wilson, a pugilist on his way to stardom, published by the Bismarck Tribune.

Sornberger lived by the idea that his title as a boxer, and later as a booze runner in the Dakotas, according to the Duluth News Tribune. Police arrested him once in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, but “four battered heads bore testimony to his prowess,” and he hacked himself out of jail with an ax.

His escape led to a “merry chase” and a maze of gun battles, until he fled to a logging camp, found work, and then nearly killed someone with a stone jug.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Sornberger went down the scale again from prizefighter to bartender to biscuit shooter in a lumber camp,” the Evening Journal reported. “He was a good cook, but a bad man.”

Sornberger found whiskey. “The man began to drink as if he had a thirst that would drain all the whisky barrels in the state. Drinking and fighting go together, but a hard drinker does not make a hard fighter,” the Duluth News Tribune reported on September 5, 1909.

Higgins, the first "lumberjack sky pilot," found Sornberger, a man after his own heart while he was hiding in the woods near Walker, Minnesota, after the assault, according to the Evening Journal.

News reports at the time were not clear on why Sornberger was one of the most wanted criminals in Minnesota. He was banned from the state, and sheriffs were hunting him. that Sornberger was wanted for murder, while other newspaper articles said he ran prostitution rings and that he was a bootlegger.

“Higgins found him, talked to him, touched him, saw him converted, and then went around from county to county where the man was wanted for crimes and got the promise of prosecuting officers to give him a chance,” the Evening Journal reported.

“Sorenberger made good,” the newspaper stated. Sornberger straightened up, married, and began preaching with enough fervor in the logging camps to make him Higgins’ first missionary, who never went to seminary.

“The man who could fight so well with his fists for money and whisky now fought for his soul,” the Duluth News Tribune reported.

ADVERTISEMENT

Sornberger used the Bible and his fists as the tools for his new trade, often arguing for a prohibition on alcohol before 1920. When a heckler became too much, Sornberger ousted him by throwing him into a rain barrel, or with his right hook, the City of Baldwin reported. He fought off wolves with his bare hands while traveling between the camps.

And he fit into the camp culture. He earned a fourth name, “John the Baptist of the North Woods,” a man who struck out at sin with all the vim and unleashed fury with which he struck out at his opponents in the squared circle or the barroom of other days,” the Duluth News Tribune reported.

“Evangelists like Sornberger had an advantage in speaking at logging camps because they spoke the language of the camps and they were also big men physically,” the City of Baldwin reported.

For instance, Sornberger knew camp food lingo. He called donuts "sinkers," cookies "barn doors," beans with pork "whistle berries,' and coffee "swamp water."

, the pseudonym he used to keep away from the law. publicized that he would be speaking.

“He led a reckless life after that until finally with five gunwounds he took refuge from the law in a lumber camp,” according to the Fargo Forum on February 27, 1926.

in Minnesota after being a rural missionary for 32 years, according to the Minneapolis Journal.