Editor's note: This archival Vault article was first published Jan. 11, 2022.

DICKINSON, N.D. — In late summer of 1981 the world was captivated by the news that John Hinckley had pleaded innocent to his attempt to assassinate President Ronald Reagan; "Endless Love" by Diana Ross and Lionel Richie swept the airwaves of FM radios and a newly launched cable television channel premiered as MTV.

ADVERTISEMENT

In North Dakota, Priscilla Dinkel, 53, and her 7-year-old granddaughter were loading up their Oldsmobile Cutlass to move the 364 miles from their hometown of Crystal, North Dakota, to the oil booming badlands of the Western Edge, where Dinkel’s daughter had moved prior and found opportunity.

Three months later, on a cold November morning, both Dinkel and her granddaughter would be found brutally murdered at a motel in Dickinson — the crime so gruesome and heinous that it would garner national media and law enforcement attention, before going cold for a decade.

The boom

In 1973, North Dakota was in the midst of its second oil boom when then-Gov. Art Link would take to the media circuit to appease those in the west by claiming that the oil boom was nearing its end.

“When we are through with that and the landscape is quiet again … let those who follow and repopulate the land be able to say our grandparents did their job well. The land is as good and, in some cases, better than before.”

Eight years later, in 1981, the reality would set in that the oil boom in the Williston Basin was far from over. For decades it continued, fueled by new drilling techniques and innovations that would keep the black gold flowing at breakneck speeds as thousands of new wells would be drilled across the western part of the state.

With the boom would come a growing stream of revenue, dreamers, crime and murder to the once economically depressed and sleepy region.

By the time Dinkel would leave her hometown for her own opportunity to manage the Swanson Motel, at 746 W. Villard St., in Dickinson, the oil fields were pumping out more 124,000 barrels per day. Dickinson’s population had grown by nearly 7,000 people in a few years, and the motel Dinkel would manage was well known in town for housing many of the transient workers who came for the opportunities the oil field provided.

ADVERTISEMENT

According to former Police Chief Chuck Rummel, who in 1981 was a patrolman and one of the first to respond to the grisly scene, police were called to the motel only a handful of times during this period and most of the calls were mundane in nature — but that would all change in the early morning hours of Nov. 9, 1981.

The slayings

The skies were overcast as temperatures hung just above freezing at 36 degrees when police received a telephone call from a neighbor shortly before 8 a.m. The phone call reported a lifeless body lying on the floor of the front office of the Swanson Motel.

“We get this call and dispatch says, ‘we just received a call that a gentleman was at the Swanson Motel and there’s a lady tied up on the floor and he thought she was dead,’” Rummel recounted the call. “Of course we go racing over there and I didn’t go in. I was on the outside because I was the rookie so I stayed out and protected the crime scene from the outside.”

Rummel explained that officers went in and stumbled onto a scene that Rummel described as “eerie.”

Dinkel was found face down in the office lobby of the motel, her hands bound with electrical cord and she had suffered a blow to the head by a blunt object.

“We hadn’t experienced, especially the police department, a homicide before so I was just saying to myself I’m so thankful I’m not in investigations,” Rummel recounted. “A little bit later as the investigation progressed, about a half an hour later, a car screams up to the motel just in time for school to start. Out this woman comes racing out of the car and I’m trying to hold her back, and I remember that she was screaming ‘my baby, my baby.’ No one could figure out what the heck she was talking about.”

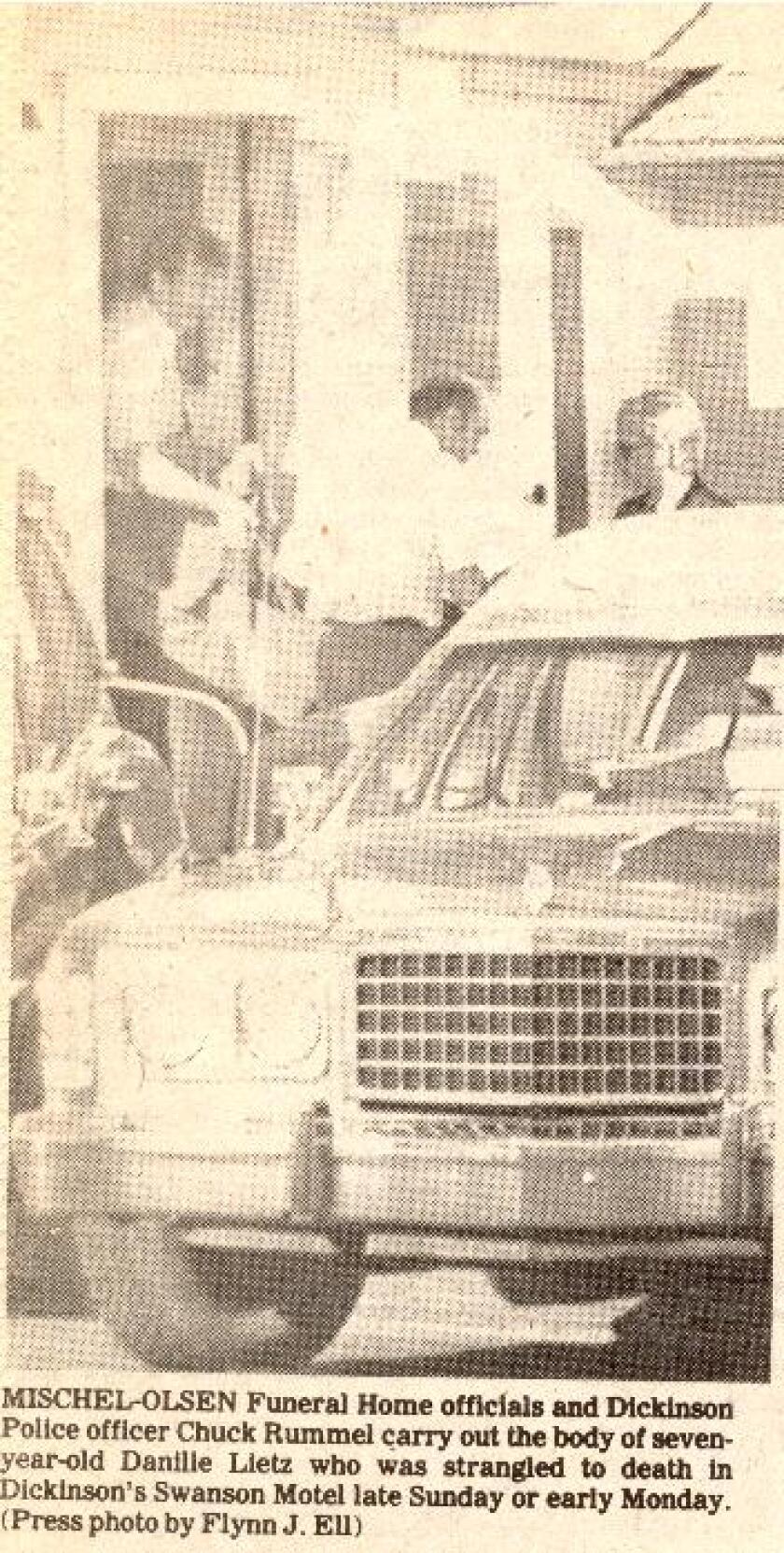

Rummel added, “At that time one of the investigators went back into the back bedroom, lifted the covers off the bed and found the 7-year-old girl.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Danelle Lietz was in the office’s sleeping quarters unbound on the bed, but evidence suggested she had been tied up at one point before being pummeled with a blunt object. A later review of the body by the coroners office would reveal she was sexually assaulted, multiple times.

“The murderer felt so guilty about that that he covered her up with the blankets,” Rummel recounted.

Rummel said that he can still remember what the two were wearing; Dinkel a blue nightgown and Lietz a Strawberry Shortcake pajama set.

In the days, weeks and months that followed, local police detectives, including then- , and state BCI detectives worked on the case in hopes of developing any possible leads.

A list of suspects was created, but ultimately several crucial pieces of information were missing, making it difficult for investigators to connect the remaining dots.

Weeks turned into months, then into years, with no new leads before the case would ultimately turn cold for 10 years.

“We were chasing ghosts. Just nothing was panning out. We were chasing down a person that was seen walking down highway 22, nobody knew him and it was the middle of the night and we were chasing that lead down before finally caught up to him somewhere in South Dakota. He didn’t turn out,” Rummel said. “So where do you go from there? The crime bureau was called in to assist … and years later when we ultimately arrested the killer, the BCI agent that was on the scene recalled seeing him watching from across the street.”

ADVERTISEMENT

By 1991, the Swanson murders drew national attention among the law enforcement community, mainly because the case had gone “cold” and a suspect wasn’t named for nearly 10 years. Around this time, a new law enforcement tool, an “FBI profile,” would provide a possible break in the case and send a Dickinson Police Detective and North Dakota Bureau of Criminal Investigation agent to a sleepy town in Arkansas, 80 miles northeast of Little Rock, in search of a suspected killer.

New tools shed new lights

In 1991, Police Commissioner Walter H. Rehling stirred interest in the case and asked the new police chief to take another look at it. Chief Paul Bazzano was head of the police department at the time and Rummel, who in 1991 was working as a detective, was assigned by Bazzano to review the cold case and develop any leads possible.

With the help of the FBI, a suspect “profile” was created and compared to the list of suspects first created in 1981. The FBI profile was a new concept in the early 90’s, and would prove to be pivotal in naming a possible suspect in the Swanson killings.

After comparing the list, Rummel believed that there was a possible match in a former taxi driver and transient who had lived in Dickinson in 1981: William Reager. The problem was that Reager had left Dickinson years earlier.

For six months Dickinson Police worked diligently to find Reager; was he even still alive?

Finally, a lead.

ADVERTISEMENT

State troopers in Arkansas had stopped Reager and ran his information through the national database. Dickinson Police had their man, but he now lived in Batesville, Arkansas, more than 1,240 miles away.

Within days, Rummel and a representative with the state BCI office were enroute to Batesville to interview Reager on the cold case.

“The second day we were in Arkansas, they picked him up and brought him to the Sheriff’s Office told him he was under arrest for an unrelated crime, having two wives, and here we are in this little dinky Sheriff’s Office in this little town and that is where we interviewed him,” Rummel said. “Prior to interviewing him I reached out to the FBI and asked them how I could get him to confess, and they said to take my time. It could take up to four days for someone with his profile to confess. They wanted me to work the angle of the little girl, because they said he felt guilty about that.”

During the interview, Rummel noticed that “many traits of the FBI profile were glaringly obvious in Reager.”

“I walk in and sit directly in front of him, the BCI agent sits off to the side, I start in,” Rummel says. “I said, ‘do you remember me?’ and he said, ‘yeah, I don’t remember your name but I know you’re from Dickinson and you’re a cop.’ I then said, ‘you know what we are here for,’ and he said, ‘no,’ and I said, ‘we’re here to finally take care of the business when it comes to the Swanson motel.”

After hours of interviewing, Reager finally confessed to the murders and gave very vivid details of the murder that only law enforcement or the suspect would know. He confessed to Rummel that he wanted to date Dinkel’s daughter, but she did not approve of him.

Rummel learned during the interview that Reager had babysat Lietz when he lived in Dickinson.

ADVERTISEMENT

“This man remembers ever detail, things that no one else would have known and this is 10 years later,” Rummel said. “When it came to the part of the sexual assault on the little girl he would just say, ‘I did things I wish I had never done to her’ and the BCI agent would step in and say I need to hear exactly what you did’ ... and he finally came out and said, ‘I raped a little girl.’”

Reager was subsequently arrested and charged with the murders of Priscilla Dinkel and 7-year-old Danelle Lietz. However, in a wicked twist of fate, Reager would die in jail from a heart attack four days before the beginning of his trial.

The Swanson murders are used as case studies for FBI profiles in many criminal justice universities around the nation and has sparked the interest of A&E Television and their series “Cold Case Files.” A large portion of this story was courtesy of invaluable information provided by the Dickinson Police Department’s website, podcast and other publicly sourced information.