This is Part 5 of the Minnesota Vice series.

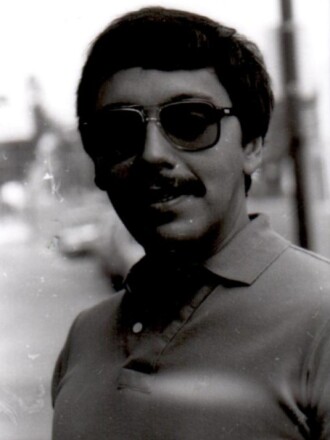

KEY BISCAYNE, Fla. ŌĆö Today was the day that would wreck Casey RamirezŌĆÖs life, but at the moment, his biggest immediate problem was the banners.

ADVERTISEMENT

He had paid two aircraft to fly over the beach at Key Biscayne, trailing banners behind them.

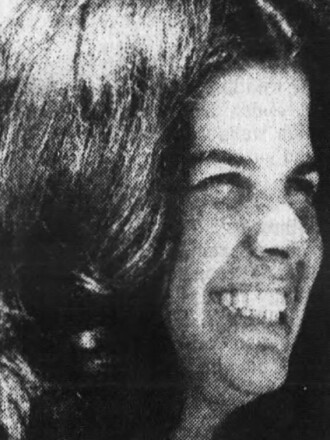

The first was a declaration of love for his girlfriend Pamela Jackson, or P.J, as he called her. The second was a vulgar message for two members of his crew, pilots Kent Moeckly and Greg Schmidt. It was going to be a great joke.

Tomorrow, Jackson would abruptly leave him and fly back to California, angry at him. Before long, they would break up. Next year, Ramirez and Moeckly would be convicted of federal cocaine charges. Schmidt would flip on his pals and be the prosecutionŌĆÖs star witness.

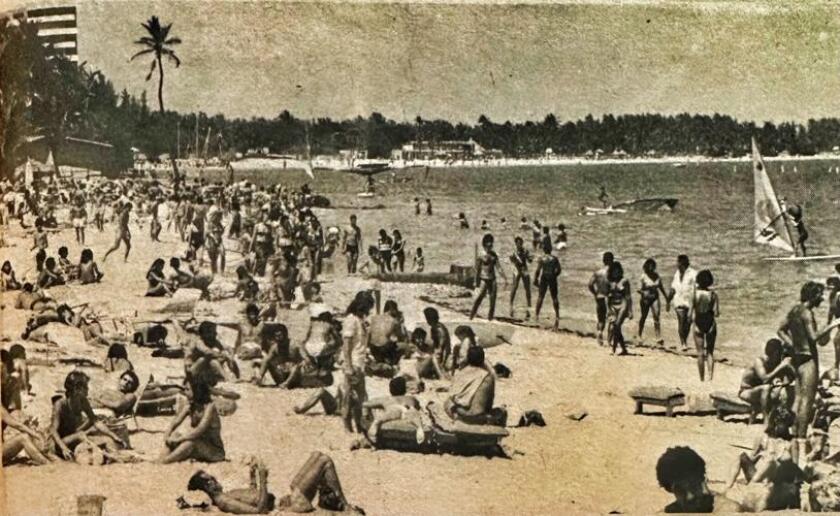

But that was later. Today was April 23, 1983, and life seemed pretty good, considering Ramirez and his crew were in the midst of a major drug smuggling operation. So where were those planes?

They had all awoken at daybreak as Ramirez had insisted. He had hustled all four of them from the Silver Sands Motel to breakfast and down to the beach on the Atlantic coast for the big show.

The beach could be crowded, but this early only a few people were there. It was windy, about 30 mph gusts. Some people were practicing wind surfing on the sand.

Finally a low hum, and there was the first plane overhead, streaming its banner. But instead of the declaration of love, it carried the message for his friends: ŌĆ£Kent and Greg, sit on it and rotate.ŌĆØ

ADVERTISEMENT

Oops.

Then the love banner flew past, and the plane circled back around. Ramirez scratched a heart into the beach sand. Greg snapped a photo of Ramirez and Jackson embracing in front of a heart, as the plane flew overhead with the most important banner: ŌĆ£P.J., I love you. Casey.ŌĆØ

The planes circled back around. The foursome looked up, shading their eyes against the morning sun.

It was just like Ramirez to make an extravagant gesture paired with a bit of humor. And never more so than at this moment.

Despite the light-heartedness, there was a deep underlying anxiety in this group.

Their friend ŌĆ£Uncle BillŌĆØ Coulombe was now likely airborne, returning from a ŌĆ£missionŌĆØ far to the south.

TWO DAYS BEFORE THE BUST ŌĆō APRIL 21, 1983 - Pembroke Pines, Florida

It was evening outside a row of modest townhouses in the Miami suburb of Pembroke Pines. A trio of men stood near the townhousesŌĆÖ mailboxes.

ADVERTISEMENT

It was Thursday, April 21, 1983.

One of the men, a man with Hispanic features and a tousled, boyish haircut, was in charge. Casey Ramirez. Standing with him, deep in conversation, were two tall white men.

ŌĆ£Casey was talkinŌĆÖ about a ŌĆśmission,ŌĆÖŌĆØ Schmidt recalled later in court testimony.

Specifically, who should fly it.

Ramirez had brought the two men outside the townhouse with him because he was convinced the feds were listening in.

ŌĆ£Casey was paranoid that the townhouse was bugged, and he didnŌĆÖt want to talk in the townhouse or on the telephone,ŌĆØ Schmidt said.

He wasnŌĆÖt entirely wrong to be concerned. The federal team investigating Ramirez had been surveilling and tracking activities at the townhouse for some time now.

ADVERTISEMENT

Ramirez decided: The pilot for tomorrowŌĆÖs ŌĆ£missionŌĆØ would be Bill Coulombe, or as Ramirez called him, "Uncle Bill, and he would get paid $50,000 upon his return.

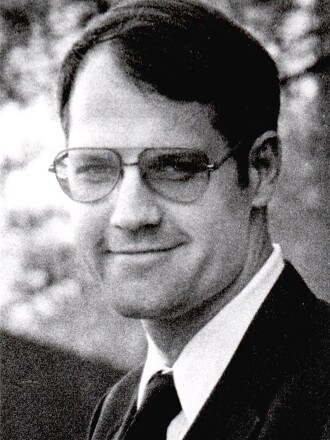

Coulombe was an experienced pilot. He had been flying for Ramirez since 1981 and at age 56, was the most senior pilot in RamirezŌĆÖs crew in both age and experience. He was a tall, lanky man, who sometimes wore cowboy boots.

Coulombe had flown for the CIAŌĆÖs secret Air America transport service in the Vietnam conflict, where his colleagues nicknamed him ŌĆ£The PriestŌĆØ because of his faithfulness to his wife, his Catholic devotion and his strict avoidance of drugs and drinking. He was now retired.

He was brother to Lois Bredemus, RamirezŌĆÖs ŌĆ£momŌĆØ of his adopted family in Princeton. Hence, "Uncle Bill."

These days, besides flying for Ramirez, Coulombe was trying to get a fishing business going in Rockport, Texas. The $50,000 would go a long way toward jumpstarting his plans.

Schmidt, an Republic Airlines maintenance supervisor in Minnesota, had met Coulombe in Arizona in 1979, and Ramirez a few years later.

Schmidt was a regular pilot for Casey, ferrying aircraft and such. But he had never flown the main event, the long journey south and back.

ADVERTISEMENT

The trio went back inside, and Schmidt helped another of RamirezŌĆÖs flyers, Kent Moeckly, make a half-dozen sandwiches for CoulombeŌĆÖs long flight tomorrow ŌĆö bread, butter, bologna.

They put the homemade sandwiches in a plastic bag, in a fridge. Then they all hit the hay.

ONE DAY BEFORE THE BUST ŌĆō April 22, 1983 - Ft. Lauderdale-Hollywood Airport

The next morning they awoke early, about 4:30 a.m., before sunrise.

Ramirez, Coulombe, Schmidt and Moeckly left the townhouse and got coffee.

As the sky lightened into dawn, they drove to the Sunny South Aviation hanger at the Ft. Lauderdale-Hollywood Airport, a sizable airport in the Miami area.

One of RamirezŌĆÖs small fleet of Cessna aircraft was parked outside on the airport tarmac.

There, the four men went to work. They placed five blue 15-gallon gas containers in the passenger compartment in the plane Coulombe was going to fly that day ŌĆö a Cessna Turbo 210N. It was painted light tan with blue stripes down the side. It was N6608C, "6608 Charlie."

ADVERTISEMENT

They connected the gas containers to a pump in the plane that would push fuel from the plastic containers into the wing tanks.

This lengthened the planeŌĆÖs range. Each plastic fuel container gave the plane about an additional hour of flying time.

Schmidt and the others put survival gear, a raft and tools, maps of the Caribbean and South America, and for CoulombeŌĆÖs long ŌĆ£mission,ŌĆØ soda pop and the sandwiches made at the townhouse the night before.

Then a Hispanic-looking male, who didnŌĆÖt seem to speak English, hopped into the Cessna, crouching down in the passenger seat so nobody could see him on takeoff.

Ramirez knew him. He was to be the navigator. Coulombe would fly across the ocean, the navigator would make sure he landed in the right spot in the jungle.

With the navigator ducked down low, Coulombe taxied out, his plane heavy with aviation fuel from his topped-off wing tanks and the gas cans behind him in the cockpit, and took off into the warming sky. He had hours of flying ahead of him.

For everyone else, it was time to wait.

Ramirez seemed to be in a jubilant mood. It was time for a Friday night out. The four drove from the townhouse to the Silver Sands Motel in Key Biscayne.

Miami had always been sun-soaked retirement destination, but it wasnŌĆÖt considered particularly glamorous in April 1983.

It was about this time that a television writer named Tony Yerkovich took a drug-fueled boat ride into Miami harbor and envisioned a TV show that would become ŌĆ£Miami Vice,ŌĆØ a hit show about stylish cops fighting crime in a cocaine-saturated tropical paradise.

The show would remake MiamiŌĆÖs image and spark an entire generationŌĆÖs neon dreams. But the showŌĆÖs pilot wouldnŌĆÖt air until late next year, September 1984.

In reality, Miami didn't look like a color-soaked TV show. Miami was sunbaked beige, corrupted by the booming drug business, and many there were bone-tired of it all.

Silver Sands was a one-story beach resort that looked out over the ocean. It had been built in 1956 and was a staple on the beach. It had long been a popular destination for tourists and locals alike, and while it might be showing its age a little, many considered it a throwback, even charming.

The group opted for a Japanese restaurant that evening before going to bed.

THE DAY OF THE BUST ŌĆō April 23, 1983, 1 p.m., Pembroke Pines, Florida

Back at the Pembroke Pines townhouse the next day, Ramirez told Schmidt and Moeckley that Coulombe was on his way back, and should return just before sunset.

Meanwhile, there was some work to be done. They got ready to do what Ramirez called ŌĆ£flying cover,ŌĆØ keeping an eye out for both a returning Coulombe and patrolling Customs aircraft. Both pilots had flown cover before.

On RamirezŌĆÖ instructions, Schmidt and Moeckly headed back to the airport and each got in their own small Cessnas, heading to Boca Raton Airport where they would circle the airport, landing and then immediately taking off, a procedure known as a ŌĆ£touch and go.ŌĆØ

They would look like they were practicing landings. In reality, they would essentially be circling, keeping their eyes open.

Flying cover.

Ramirez told them the radio frequency they should all use and told them to flip their radio call signs to let the group know that they had spotted Customs aircraft.

Ramirez would be flying a Cessna with the tail number N5296Y, so he would combine the planeŌĆÖs ID with his own flipped initials as a radio call-sign: 96CR, for Casey Ramirez. Over the radio, if all was well, he'd identify himself as ŌĆ£Niner-Six-Charlie-Romeo.ŌĆØ

But if something went wrong, he would sound the alarm by flipping his initials backward: 96RC or ŌĆ£Niner-Six-Romeo-Charlie.ŌĆØ

The Miami area was littered with about a dozen airfields large and small, some busy ones with air traffic control towers and others were quiet non-commercial airfields. Some were essentially paved landing strips. Unguarded.

Ramirez assigned a codeword to use for each significant local airport that could be a landing location: Alpha for Boca Raton, Bravo for Fort Lauderdale-Executive, Charlie for Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood and Delta for the practically deserted Opa-Locka West.

ŌĆ£Bill Coulombe would be returning through a corridor projecting northeasterly from an area between Boca Raton Airport and West Palm Beach,ŌĆØ Schmidt later testified in court. ŌĆ£Casey would be flying in that area along the coast, be lookinŌĆÖ for Bill.ŌĆØ

All three took off, each piloting their own planes ŌĆö three small specks aloft in MiamiŌĆÖs busy airspace, circling between scattered cumulus clouds.

They were airborne for about an hour when Schmidt heard Coulombe on the radio, and Ramirez.

ŌĆ£Niner-Six-Romeo-Charlie,ŌĆØ Ramirez said, using his flipped callsign. That was it, the alarm signal. Something had gone wrong.

Ramirez must have seen something. He was warning Coulombe. DonŌĆÖt go to Alpha, Bravo or Charlie, Schmidt heard Ramirez say. Essentially, avoid Florida.

Coulombe responded with his own flipped call sign. Red alert.

ThatŌĆÖs when Schmidt saw a plane and a helicopter in the sky that looked to be U.S Customs Service. Uh-oh.

Schmidt heard Ramirez talking to Coulombe about remaining fuel, and told him to go somewhere called the ŌĆ£west end.ŌĆØ Where was that?

It was all going sideways. Schmidt, extremely nervous, headed back to the Boca Raton Airport with Moeckly.

Upon landing, they almost ran their planes into each other.

Inside, out the heat, Schmidt asked Moeckly: Where was Coulombe going? Where was the ŌĆ£west end?ŌĆØ

Moeckly seemed to know.

The Bahamas.

THAT AFTERNOON, 4:30 P.M. ŌĆō over Grand Bahama Island

Customs pilot James McCawley had pulled up his twin-engine plane tight alongside the fleeing Cessna. He noted its tail number: N6608C. "6608 Charlie." Light colored with blue trim.

The Cessna was trying to land on the Grand Bamaha islandŌĆÖs West End airfield. It circled around twice, wheels down, acting like it was going to land.

McCawley stayed on the Cessna, flying off its wing, less than 100 feet away. Practically flying in formation through the hot, hazy Bahamas air. They were close, predator and prey.

His co-pilot snapped photos of the plane and its pilot, an unidentified man.

It was Bill Coulombe.

Coulombe broke off then and juked back to the island coast, then sped up and swung low, lining up with a long, straight road, looking to land

This was Perimeter Parkway, a grandly named yet remote road in the jungle scrub of the island interior.

It was a notorious landing spot for drug smugglers, including some who never managed to make the landing. The wreckage of several planes festooned the sides of the road.

Coulombe was, whether he knew it or not, flying into a narrow gap in law enforcement coverage.

The Bahamas was a different nation. The U.S. had recently gotten for its government pilots to patrol into Bahamas airspace, but that permission didn't extend to chasing or apprehending suspects on land.

Bahamanian officials could arrest smugglers on their own soil, of course, but in early 1983 they werenŌĆÖt communicating with U.S. agencies in real time about suspects chased onto remote island roads, like Coulombe.

The Cessna made the landing, McCawley saw him touch down. The Customs pilot pulled up and circled the area. His quarry was so close, but so far away.

Down below, Coulombe was frantic. He knew the Customs plane was somewhere overhead and he could hear the thwack-thwack of an approaching helicopter. He felt hunted.

He jumped out of 6608 Charlie's cockpit, leaving the plane key still in the ignition, and fled into the foliage on the side of the road ŌĆö low scrub bushes interspersed by palm trees.

The key wasn't all Coulombe left behind.

The CessnaŌĆÖs cockpit was littered with trip snacks, candy wrappers, empty soda cans and sandwich bags.

There were flight maps for the Caribbean and Colombia including math notations made with a ballpoint pen: a "180," a "22" and ŌĆ£396.ŌĆØ (In cocaine terms, 180 kilos, times 2.2 conversion rate, equals 396 pounds.)

There were also, in the back, several large green canvas duffel bags.

Just then, Customs pilot Vincent Tirado in his UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter arrived on scene, newly refueled and coming in for a closer look at the ditched Cessna on the remote road ŌĆö the most the U.S. pilots could really do.

Observe and report.

He pulled out his camera.

The Black Hawk hovering about seven feet above 6608 Charlie, the helicopter rotor's powerful downdraft flattening back the scrub brush and buffeting the small craft, pushing it slightly off the road into the adjacent grass.

Tirado peered into the plane but didn't see a pilot. He did see something significant, though.

ŌĆ£I saw green duffel bags in the rear of the aircraft,ŌĆØ Tirado said.

In this part of the world, that usually meant only one thing:

Cocaine.

THAT EVENING - 9:30 p.m., over the Atlantic Ocean

Schmidt was back airborne, flying around thunderstorms in the dark. Lightning flashed between clouds as he headed due east from Miami.

Ramirez had called. He was in Freeport, on Grand Bahama Island. He didnŌĆÖt say it on the phone, but he had followed close behind Coulombe and the feds, tailing the chase to The Bahamas.

Not long after U.S. Customs aircraft left the area above CoulombeŌĆÖs ditched plane, Ramirez had flown over, and had been incensed to see the Cessna still intact.

Ramirez didn't say any of that over the phone. Who knows who might be listening. Instead, he said he wanted Schmidt to fly to Freeport ASAP with $500 cash and a tool set, allegedly to fix something on RamirezŌĆÖs plane.

Schmidt landed and met Ramirez at the Freeport airport. It was about 10:30 at night ŌĆö the airport was closing.

On the tarmac, Ramirez quickly filled Schmidt in on what was actually happening.

ŌĆ£Bill CoulombeŌĆÖs down, the airplanes down,ŌĆØ he said.

In a borrowed car, the two headed away from the airport, down the main island highway, into the jungle scrub.

The plane was probably a lost cause. Instead, they would look for Coulombe, but would have to do so carefully.

They were driving into a maze. Real estate developers had carved out an entire townŌĆÖs worth of roads into the middle, forested part of Grand Bahama Island, including Perimeter Parkway, where Coulombe had landed.

From the air, it looked like a lot of people might live here ŌĆö lines in the bush marking neighborhoods and cul-de-sacs. But in reality, none of these development dreams had come true.

These were ghost roads. The biggest and longest was Perimeter Parkway, partly paved, partly dirt.

ŌĆ£We got out away from the airport, and I think it was away from any buildings, or ŌĆö it was kind of like out in the jungle, and Casey was calling for Bill out the window as we were driving,ŌĆØ Schmidt said.

No luck.

Schmidt and Ramirez got out and walked down the road looking for him, calling into the bush.

This morning they had been relaxing on a Florida beach. Now they were tramping through the jungle scrub in the Bahamas, slapping insects, looking in vain in the dark.

Coulombe should have burned the plane, Ramirez said, but he had flown over the landed plane and knew he hadnŌĆÖt. Ramirez was upset. But he also wanted to reassure Schmidt. He said he takes care of his men ŌĆö heŌĆÖd get Coulombe out of this.

They finally found Coulombe, who emerged from hiding for hours in the underbrush. He was injured, dehydrated, smelly, and punctured with insect bites.

ŌĆ£It was mostly a glad-to-see-you-youŌĆÖre-okay reunion,ŌĆØ Schmidt said.

They had to leave. For all they knew, the authorities were right on their tails.

Ramirez yelled at Coulombe as they drove back to Freeport to the Princess Hotel, a new and sprawling resort and casino, considered the nicest place in town.

They only had one room for all three of them ŌĆö the hotel was full. One of them was going to sleep on a cot. It was pushing 2 a.m.

They went to the bar, and sat at a table. It was near closing time. Coulombe was still shaken up from the dayŌĆÖs events and ordered drinks. Schmidt drank a Coke.

ŌĆ£Damn, 400 pounds,ŌĆØ Coulombe said.

Ramirez angrily cut him off.

ŌĆ£You should have burned it,ŌĆØ he said.

Back in the hotel room the three were going to share, Coulombe was still nervous, and wanted to smoke a cigarette, setting off a whole new argument with Ramirez, who didnŌĆÖt drink or smoke.

It all made for an anxious, uncomfortable night.

THE DAY AFTER THE BUST - April 24, 1983

The arguments didnŌĆÖt end the following day, even after Ramirez, Schmidt and Coulombe made it out of the Freeport airport without any trouble, flew back to the U.S., cleared customs (their plane was registered to ŌĆ£John KeyŌĆØ) and returned to the Pembroke Pines townhouse.

Ramirez and Jackson got into it ŌĆö a loverŌĆÖs spat. Ramirez had lied to her the previous day about where they were and now had to come clean. She would get on a jet for San Diego that afternoon.

Then Coulombe and Ramirez were arguing again. Coulombe wanted to get paid. He needed that $50,000.

That day both Schmidt and Moeckly flew back to Princeton, Minnesota. So far away from Miami.

The word of the capture of 6608 Charlie quickly made its way to the DEA field office in Minneapolis.

Michele Leonhart, John Boulger and Ed Fisk, the investigators on the Ramirez case, were all in the office when the word came in. It was a bombshell of the best kind.

ŌĆ£Michele did her happy dance,ŌĆØ Boulger recalled, remembering ŌĆ£elation.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£I was screaming,ŌĆØ Fisk said.

ŌĆ£I remember, it was like ŌĆśThis is it, this is it, this is what we were waiting for,ŌĆÖŌĆØ Leonhart said.

She knew 6608 Charlie well. It was one of the planes she spotted when she undercover at the Princeton fly-in in 1981.

After getting burned undercover, after two years of painstaking investigative work, this finally might be the big break they needed.

They could finally bring Ramirez down.

<<< Read Part 4

Read Part 6 >>>

Follow the series

Notes: This article is based on interviews with Boulger, Fisk and Leonhart, as well as Ramirez trial transcripts stored in the National Archives in Chicago, The DEAŌĆÖs Schmidt investigative report in Judge Edward J. DevittŌĆÖs papers in the Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections at the University of North Dakota, the archives of the Islander News of Key Biscayne, by Jane Wollman Rusoff in the Television AcademyŌĆÖs Emmy Magazine, Google Earth, photo archives, copies of Florida and Minnesota newspapers archived by and the Florida Memory project by the State Library and Archives of Florida. Ramirez, Moeckly and Jackson never responded to requests for an interview. Schmidt declined an interview request. Coulombe died in 1994.