This is Part 6 of the Minnesota Vice series.

MINNEAPOLIS ŌĆö Casey Ramirez was scrambling. So, like he so often did, he decided to do something audacious.

ADVERTISEMENT

He went straight to the feds.

It was May 3, 1983.

Ten days before, he had been rescuing his pilot, Bill Coulombe, from the jungle undergrowth in The Bahamas after Coulombe landed and abandoned a small plane full of hundreds of pounds of cocaine for investigators to scour for clues.

As investigators would soon figure out, the plane was directly linked to Ramirez. It was registered to him. His fingerprints were on the maps inside. On torn stickers affixed to equipment in the plane was Ramirez's name, and the name of Princeton, Minnesota.

Meanwhile, Ramirez's crew was falling apart.

Coulombe, old "Uncle Bill," was still with him, like always. So was assistant Kent Moeckly. But after the debacle in Florida, his girlfriend, Pamela Jackson, had left him and flown back home to San Diego.

Another pilot, Greg Schmidt, had flown back to Princeton and seemed to be distancing himself, moving his things out of RamirezŌĆÖs hanger into those owned by other friends.

ADVERTISEMENT

Then RamirezŌĆÖs attorney, Ron Meshbesher, got in touch. He had been advised by the U.S. AttorneyŌĆÖs Office in Minneapolis on April 25 that Ramirez was the target of a federal grand jury investigation.

The heat was on.

So here was Ramirez in enemy territory, in the federal building in downtown Minneapolis, bluffing. He sat down and met with DEA Special Agent in Charge Steven Cummings and spun him a story.

ŌĆ£Ramirez indicated he had been approached by individuals to fly ten 400 pound loads of cocaine from Colombia to the United States for which he was to receive $100,000 per load,ŌĆØ a court document stated.

He offered to help the DEA with its investigation into this matter.

It was hard for the DEA to take seriously. By this time, of course, its joint task force investigation into Ramirez was two years old, and the agency had just gained crucial evidence in the form of RamirezŌĆÖs downed plane in The BahamasŌĆöof him running just kind of ŌĆ£missionŌĆØ he was describing. And Ramirez knew it.

Needless to say, the DEA was not interested in Ramirez's offer to help.

ADVERTISEMENT

This wasnŌĆÖt the last time Ramirez reached out to the feds. In fact, over the next year, he appeared to make a habit out of it.

In a later pretrial court motion filing, Assistant U.S. Attorney Thor Anderson wrote almost a plaintive note about RamirezŌĆÖs regular pestering.

"The defendant Ramirez has the annoying habit of calling government lawyers and law enforcement agents on the telephone and sharing with such auditors the deepest confidences, most of which are probably not true and some of which are arguably incriminating,ŌĆØ Anderson wrote.

Michele Leonhart, the DEA agent investigating Ramirez, said the DEA meeting and the random phone calls were his way of trying to get information.

ŌĆ£Casey would call somebody and try to cooperate. But it was never about him. He was just fishing,ŌĆØ she recalled in a recent interview.

MAY 1983 ŌĆö Minneapolis

The team investigating Ramirez was now on a roll. It had gained some additional firepower by early 1983.

The Reagan Administration, looking to escalate its War on Drugs, created a new kind of multi-agency task force in late 1982, mirroring the South Florida joint task force that had seemed so successful.

ADVERTISEMENT

It was called the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force program, and the country was subdivided into 12 regions, each with its own OCDETF.

The Ramirez case was numbered Z001, the first task force case out of the Minneapolis office, in the North Central OCDETF.

The new task force structure was designed to break down barriers between agencies ŌĆö such as the DEA, the FBI, the IRS and others ŌĆö so they could more easily work together to investigate an individual or organization, like Ramirez and his crew.

Of course, the Ramirez investigative team ŌĆö Leonhart and John Boulger with the DEA and Ed Fisk with the IRS ŌĆö was already essentially working as a joint task force. But making Ramirez an OCDETF case also opened up more funding.

ŌĆ£Our bosses told us, ŌĆśWell, to do this case, itŌĆÖs bigger than our little Minneapolis budget. And this is a separate pot of money that we can use for our travel, for informants, for investigative expenses,ŌĆÖŌĆØ Leonhart said. ŌĆ£So we wrote it up.ŌĆØ

The team soon had a few surprises for Ramirez and friends.

The U.S. attorney had approached Jerry Davis, the one-time Princeton Co-op Credit Union manager, with a plea deal that involved taking a lie detector test and answering questions about Ramirez.

ADVERTISEMENT

ŌĆ£We thought Davis would roll over,ŌĆØ said Boulger, in a recent interview. ŌĆ£He's the odd man out on the whole deal.ŌĆØ

Davis, who was now the manager of the Ramirez-bankrolled Princeton ice arena, declined the offer because it didnŌĆÖt include assurance Davis would avoid prison.

Instead, now, he would face a jury trial.

On May 5, 1983, Jerry Davis, former manager of the Princeton Co-op Credit Union, was indicted on 15 charges of illegally failing to file records of currency deposits totaling $962,256.

The indictment didnŌĆÖt mention Ramirez, but it seemed highly likely the indictment was connected to DavisŌĆÖ involvement with RamirezŌĆöat least that was the claim of an unnamed source printed in Minneapolis Tribune reporting about the indictment.

The Princeton Union-Eagle provided the context for that quote.

ŌĆ£Davis, 37, resigned as manager of the credit union in October 1981 and shortly thereafter became manager of the Princeton Youth Hockey Arena which was built with a $500,000 interest-free loan provided by Casey Ramirez,ŌĆØ the indictment article stated.

ADVERTISEMENT

Davis pleaded not guilty.

Davis was a well-known and respected member of the community. The Princeton paper, in an editorial entitled ŌĆ£Indictment is not a conviction,ŌĆØ cautioned readers to let the justice system process play out.

ŌĆ£One thing is certain, Davis would have no lack of willing character witnesses if they should be sought,ŌĆØ the editorial opined. ŌĆ£He has had an exemplary career of private and public service.ŌĆØ

Later, during the trial, Ramirez claimed he had been asked to stay away from the courtroom because his presence might intimidate jurors.

MAY 13, 1983 ŌĆö The Bahamas

The week after Davis' indictment, Leonhart and Ed Fisk, the lead IRS member of the federal task force, flew commercial to The Bahamas to examine evidence from RamirezŌĆÖs ditched plane.

They got a happy reunion with 6608 Charlie, Ramirez's Cessna 210, at the Freeport airport. Bahamanian police pulled out the spare fuel tanks and the avionics ŌĆö the radios and other electronics ŌĆö gathering information about where they were installed, how they were linked to Ramirez.

There were the stickers and labels tying the gear to Princeton and Ramirez himself. Maps of the Caribbean and South America in the cockpit were bagged as evidence.

ŌĆ£It was just unreal, because this was exactly what we needed. And 6608 Charlie was one of the first planes we knew,ŌĆØ Leonhart said. ŌĆ£It was my impression that 6608 Charlie was one of CaseyŌĆÖs favorite airplanes because he was in it, or on invoices for it, quite often.ŌĆØ

The Bahamanian police had opened one of the 12 duffel bags from the plane, cutting off the locks that held it shut and snipping open the top. They then opened the rest, finding a total of 181 plastic-wrapped packets of white powder. Each weight a kilogram. One hundred eighty one kilos, about 400 pounds.

To nobodyŌĆÖs surprise, they tested positive for cocaine. The Bahamanian police agreed to send a sample to Minnesota to be tested.

The evidence from The Bahamas was quickly adding up.

ŌĆ£I think we would have had a conspiracy case but it would have been based on witness testimony and would have been a lot harder to prove,ŌĆØ Leonhart said. ŌĆ£This should have put to rest what he was smuggling. It would have taken us more time. We were getting there, though.ŌĆØ

Fisk was making strong progress on a separate income tax case against Ramirez, but the drug smuggling side of the investigation was taking more time.

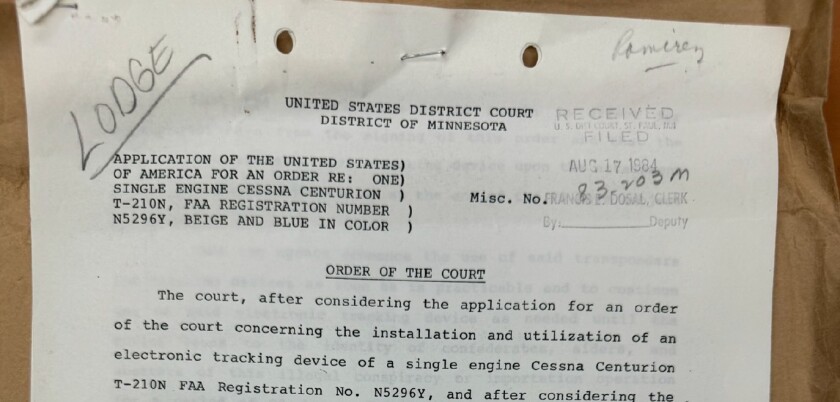

In August 1983 the investigative team got a judgeŌĆÖs approval to place a tracking device on 5296 Yankee, the Cessna that Ramirez had been flying over Miami the day Coulombe and the cocaine went down in the Bahamas. They suspected Ramirez was still running drugs.

Boulger said the team estimated Ramirez had run about 10-11 other drug smuggling flights before 6608 Charlie was ditched in April 1983 ŌĆö two years after he made national headlines for the City Hall palm trees and a year after the WCCO I-TeamŌĆÖs expos├® aired.

ŌĆ£They would have screwed up sooner or later,ŌĆØ Boulger recalled in a recent interview. ŌĆ£I canŌĆÖt imagine why, after all the spotlight, he would continue to do that, or why you wouldnŌĆÖt take a break for six or eight months, but yeahŌĆöthatŌĆÖs a personality thing.ŌĆØ

SEPT. 8, 1983 ŌĆö Federal courthouse, St. Paul

Davis, the former Princeton Co-op Credit Union manager, was found guilty on Sept. 8, 1983, on all counts of not reporting RamirezŌĆÖs large cash deposits. He faced up to 75 years in prison and a $150,000 fine.

The guilty finding included the credit union, meaning its very existence was imperiled. It had about $4.5 million in assets. The penalty fines, possibly up to $7.5 million, were so big they could wipe out the credit union.

While the credit union scrambled to find a way to stay open, the current management ŌĆö and the Princeton Union-Eagle newspaper ŌĆö reassured members their money was safe. The Union-Eagle, in an editorial, also seemed somewhat perplexed about the trial.

ŌĆ£It has been a difficult situation for the community, as well as for many people and one of PrincetonŌĆÖs important financial institutions,ŌĆØ it said. ŌĆ£Although serious mistakes were made no evidence was presented indicating that either Davis or the credit union received any wrongful gain from the transactions.ŌĆØ

There was no mention of two things, of which the newspaper was aware, that were prominently discussed in DavisŌĆÖ trial: his use of RamirezŌĆÖs cash to fill the tills of the credit union and the Ramirez-bankrolled ice hockey arena that Davis left the credit union to manage, to realize his dream of building up the local youth hockey program.

Floyd Bischel, the foreman of the jury that convicted Davis and the credit union, told the Union-Eagle's Mary Ellen Klas the former credit union manager was obviously ŌĆ£brightŌĆØ and knew about the Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs) he was supposed to file for RamirezŌĆÖs big cash deposits.

ŌĆ£We thought it very odd that he could remember lots of things but couldn't remember certain conversations. We donŌĆÖt think he told the complete truth,ŌĆØ Bischel said. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖll pray for him and hope that things will come out alright and I hope the judge isnŌĆÖt too strict with them.ŌĆØ

At DavisŌĆÖ sentencing in December, the prosecutor had a message for those who thought Davis hadnŌĆÖt taken pay-offs for not filing the required CTRs.

"I would submit that Mr. Davis did take payoffs,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£The building of the hockey arena was a matter of supreme importance to him and obtaining the $500,000 interest-free loan helped him achieve his dream."

Davis was sentenced to 18 months in prison, and the credit union was assessed a $30,000 fine. It had already agreed to merge with Twin City Co-ops Credit Union, a move that would eliminate any fear it would have to close.

NOVEMBER 1983 ŌĆö Princeton

Ramirez was uncharacteristically lying low as 1983 came to a close in Princeton.

It seemed the Ramirez gravy train had left the station. There was no longer any big spending, optimistic airport plans, fly in giveaways, free meals or paid-for rounds at the bar.

Ramirez even shut off his aviation fuel station at the townŌĆÖs airport, upending its operations.

"The airport had run out of gas," wrote reporter Joel Stottrup in the Nov. 3, 1983, edition of Princeton Union-Eagle, somewhat tongue in cheek.

A December article reminded readers that the Princeton food pantry was busier than ever.

Instead, Princeton was getting subpoenaed.

"Although Casey is in and out of Princeton frequently he is maintaining a very low profile,ŌĆØ wrote Princeton Union-Eagle publisher Elmer L. Andersen in his regular column. ŌĆ£Business firms and offices in the city are being requested by the Internal Revenue Service to give details on any financial transactions with Casey and the letter is signed by the same individual who did the investigating that led to the indictment of Davis."

That individual, of course, was Fisk, who leveraging grand jury subpoenas to full back the curtain on Ramirez's spending and other actions in Princeton.

The City Council found itself picking up the pieces of a number of Ramirez efforts. It was struggling to re-open RamirezŌĆÖs fuel operation so there would be fuel available at the airport. It was working with the Princeton Youth Hockey Association to figure out how to stablize the finances of the Ramirez-bankrolled ice arena.

The airport's woes worsened. Its runway was defective. Spring thawing kept causing soft spots that made it hazardous to flying. A big X was placed on the runway to show it was closed.

Pilots couldnŌĆÖt get fuel there anyway.

The council kept trying to cajole Ramirez ŌĆö or rather, whatever lawyer was representing him at the timeŌĆöto re-open the airport fuel facility.

ŌĆ£Council members decided Thursday they no longer like being the horse that follows the driverŌĆÖs carrot dangled in front of them to pull the cart forward, only to never reach the carrot,ŌĆØ wrote Stottrup in the March 15 Princeton Union-Eagle.

He quoted council member Steve VanHooser grousing about Ramirez, saying the council needed to stay on him to reach a deal: ŌĆ£If you take the pressure off, heŌĆÖs in Hawaii.ŌĆØ

By April the airport was about back in familiar territory. It was broke. It would run out of money in May, and it still had unpaid bonds for the original airport expansion under Mayor Richard Anderson to the total of $150,000. Pilots at one airport commission meeting passed a hat, raising $750 to repair holes in the airport runway.

While the Princeton City Council grappled with deteriorating operations at the town airport, and prepared to bail out its finances, it seemed Ramirez had other worries.

He contacted the DEA and IRS to tell them that he believed someone from the DEA was telling news media he was a government informant, and said he had recently traveled to Colombia to convince ŌĆ£certain unnamed individualsŌĆØ that he was not, in fact, a U.S. government informant.

This was an extremely odd thing to inform the U.S. government about.

***

Leonhart and Boulger had a personal visit to make. They were raising the pressure on RamirezŌĆÖs crew, seeking to flip them to testify about what they knew. Their targeted Schmidt, Ramirez's pilot.

In April they showed up in Minneapolis at Republic Airlines, SchmidtŌĆÖs workplace, to talk to him. They turned the screws. Schmidt was married, and was a young father to two children. He had a lot to lose if he went to prison.

ŌĆ£You better get a lawyer,ŌĆØ Boulger told him, Schmidt testified later.

In April 1984, Schmidt was indicted and charged with two counts of lying to a federal grand jury. In May, Kent Moeckly was indicted and charged with three counts of perjury in grand jury testimony. Both pleaded not guilty.

A trial jury wasnŌĆÖt convinced by the governmentŌĆÖs case against Schmidt. They acquitted him.

But by now, Schmidt had had enough.

ŌĆ£In the courtroom, after he was found not guilty, his attorney approached all of us and said, ŌĆśHeŌĆÖs going to cooperate,ŌĆÖŌĆØ said Fisk, in a recent interview. ŌĆ£We didnŌĆÖt go see him; they came to us.ŌĆØ

Schmidt and his lawyer soon had a deal in hand from the U.S. AttorneyŌĆÖs Office. Schmidt would come clean about what he knew about Ramirez and his crew. In exchange, he wouldnŌĆÖt face further prosecution.

In June, the last month Ramirez would be a free man, it seemed like the feds were everywhere in Princeton. Elmer L. Andersen, publisher of the Princeton Union-Eagle, noted as much in his regular column on June 7.

"For months, now extending into years, the IRS and the FBI have been interviewing everyone in the Princeton area who has had any relationship with Ramirez,ŌĆØ he wrote. ŌĆ£Some say the interviews get tough to the point of harassment."

Well yeah, said Fisk in a recent interview, ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs always harassment if you donŌĆÖt like the question.ŌĆØ

In early July, Jerry Davis, the imprisoned former head of the Princeton Co-op Credit Union lost his appeal over his 1983 sentencing for not filing the Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs) required for RamirezŌĆÖs big cash deposits in the credit union, which effectively laundered RamirezŌĆÖs drug money.

After the ruling he told the Princeton newspaper he believed he had done nothing wrong, and what he had done certainly wasnŌĆÖt linked to the Ramirez-bankrolled ice arena for which he became the first manager.

He said not filing the CTRs ŌĆ£did not cost anyone anything and no one was killed or raped,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£It hardly seems fair.ŌĆØ

The Princeton Union-Eagle stood by Davis, insisting in an editorial he shouldnŌĆÖt have been sent to prison, since he was a good man, was non-violent, and had a clear and clean previous record.

ŌĆ£He neither sought nor received personal gain and, as nearly as can be determined, his motivation was to accommodate a person who had aided the community in getting a youth hockey facility which was a high priority for Davis,ŌĆØ the editorial said.

Furthermore, the editorial pointed out, Ramirez had not been found guilty of anything.

But that was about to change.

It was about that time that Joel Stottrup, at the Princeton Union-Eagle, got a rare call from Ramirez. He was about to get indicted, Ramirez said. When Stottrup asked if heŌĆÖd post bail if arrested, Ramirez told him he didnŌĆÖt plan to spend a ŌĆ£dime on that bull.ŌĆØ

JULY 26, 1984 ŌĆö Princeton

On July 26, 1984, Ramirez was indicted on charges of conspiracy to smuggle cocaine, as well as tax evasion. He turned himself in, was arrested and jailed.

"THe charge of not paying taxes and his reported business transactions using paper bags of large amounts of money have added to the mystery or Ramirez," wrote Stottrup in the Union-Eagle.

The rest of Ramirez's crew ŌĆö Kent Moeckly, Bill Coulombe, Pamela Jackson ŌĆö faced the same charges. Moeckly was still dealing with grand jury perjury charges.

Schmidt was named as a co-conspirator but notably was not charged with anything.

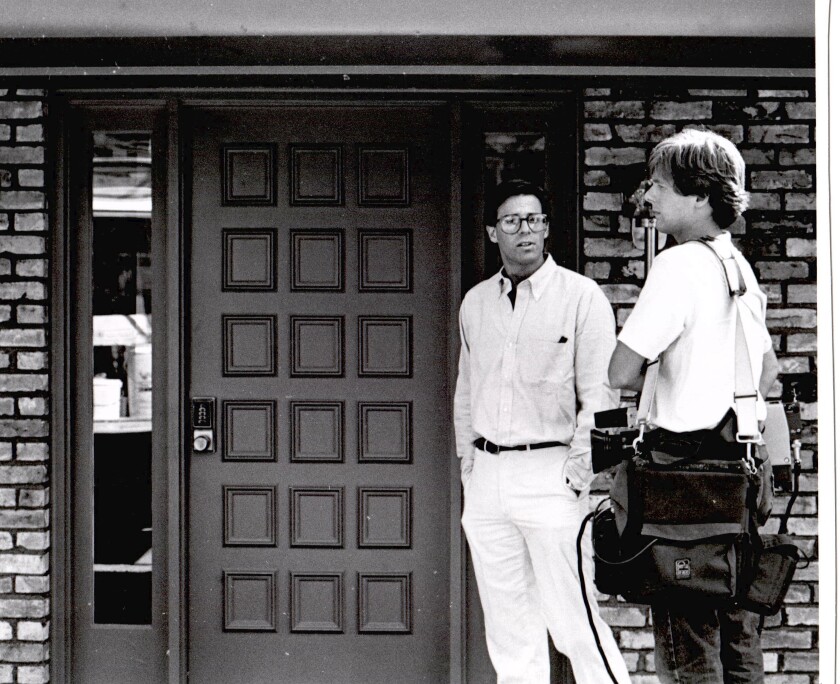

The arrest and charges hit Princeton like a thunderbolt. Now it was the mediaŌĆÖs turn to swarm Princeton, looking for quotes about Ramirez.

A WCCO TV reporter, looking for Mayor Richard Anderson, got his father Lyle instead.

ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt question where you get your money,ŌĆØ he said, before insinuating that, for all he knew, the TV reporter was involved in cocaine smuggling.

Other local residents seemed more circumspect.

ŌĆ£My grandfather settled here in the 1850s and I hate to think of Princeton being brought to the forefront as being taken in by something like this,ŌĆØ Arnold Whitcomb told the Princeton Union-Eagle.

If the accusations were true, he said, they would cancel out a lot of the goodwill Ramirez earned by his gift giving. It would mean the entire town was being ŌĆ£taken for a ride.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£People like to think of others as honest, some think otherwise, but you are supposed to be innocent until proven guilty. You don't want to offend anybody. You want to pass it out of your mind that the person isn't for real,ŌĆØ he said.

Luther Dorr, the Princeton Union-Eagle editor, directed attention in an editorial to the culpability of the Princeton City Council in allowing Ramirez so much access to town business.

ŌĆ£That, I think, is the main question Princeton, as a town, has to answer,ŌĆØ he wrote. ŌĆ£RamirezŌĆÖs trial, when it finally comes, will answer a lot of questions.ŌĆØ

Nearly 50 miles away in Monticello, Minnesota, the Monticello Times publisher called for some humble perspective, when considering the strong support there for the Northern States Power nuclear power plant in town.

ŌĆ£Before we become too critical of Princeton and its people for their romance with Ramirez, letŌĆÖs consider how many outsiders view Monticello and its citizens concerning their relationship with the nuclear plant,ŌĆØ Donald Smith wrote. ŌĆ£Because NSP has been such a tax bonanza for the governments here, the charge goes, weŌĆÖre less critical of nuclear power than we should be.ŌĆØ

JULY 1984 ŌĆö Minneapolis

The Ramirez investigative team had been preparing for this moment for months, but they were still nervous.

Despite their meticulous investigation, despite 6608 Charlie, despite flipping Schmidt, there was always the concern the trial could blow up. All Ramirez would need was one resistant juror to produce a hung jury and scuttle the trial.

ŌĆ£Any time there's a jury trial, you have a lot of angst, because it takes one juror to hang it all up,ŌĆØ Boulger said. ŌĆ£I've been through two of those in my life, and you can't figure out what you've done wrong until the judge declares a mistrial, and then the other jurors come and tell you that the one that hung it up was a whack job.ŌĆØ

The prosecution team did have a trick up its sleeve, two busted drug smugglers from Miami named William Morris and Jack Devoe who had made their own deals with the government and were prepared to tell everything they knew about Ramirez.

Morris had told Leonhart and Boulger he had been involved in the same cocaine smuggling flying subcontractor world as Ramirez in South Florida, and had even once visited him in Princeton to withdraw some money from the Princeton Co-Op Credit Union.

According to the DEA's investigative report documenting Morris' interview, Ramirez told Morris he had Princeton in his pocket.

"Ramirez said he had the people in town liking Ramirez because he kissed babies in town and did other things,'" the agents reported Morris telling them. "Morris asked if Ramirez if he was being watched and Ramirez said, 'No, I bought the cops their cars.' ... Ramirez told Morris that 'his guy' at the credit union had been fired."

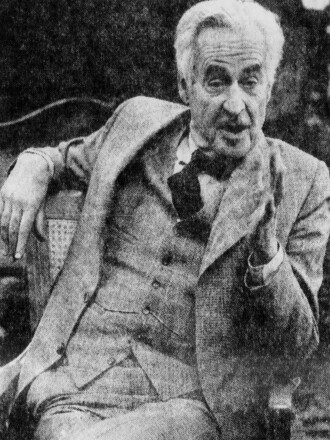

The Ramirez trial was assigned to federal Senior Judge Edward J. Devitt. He was 73, an Eisenhower appointee with a long, storied career on the bench.

In 1961 Devitt had overseen the trial of Minneapolis gangster Isadore ŌĆ£Kid CannŌĆØ Blumenfeld, arguably the biggest name in Minnesota organized crime, proclaiming at his sentencing, ŌĆ£you have led a bad life, Isadore.ŌĆØ

Devitt had co-authored the rules for Federal Jury Practice, literally writing the book on a major component of the Ramirez trial.

Devitt was known as a judge not to be trifled with by any prosecutor or defense attorney ŌĆö or a flamboyant, charming defendant.

<<< Read Part 5

Read Part 7 >>>

Follow the series

NOTES: This article was based on interviews with Boulger, Fisk, Leonhart and Princeton native Kevin Odegard, as well as Ramirez trial transcripts, microfilmed copies of the Princeton Union-Eagle archived by the Minnesota History center, material stored in the Ramirez file of the Mille Lacs County Historical Society Museum, The Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force Program (OCDETF) five-year summary report for 1983-1987 obtained via FOIA, documents about Ramirez archived by Odegard. Anderson, Jackson, Moeckly and Ramirez never responded to interview requests. Davis and Schmidt declined to be interviewed. Coulombe died in 1994. Meshbesher died in 2018.