PRINCETON, Minn. — Forty years later, I still get questions. I just don’t have all the answers. I was just 11 years old.

A few years ago at the NCAA Fargo Regional hockey tournament, I chatted up Star Tribune columnist Patrick Reusse, introducing myself as a disciple of retired Princeton Union-Eagle editor Luther Dorr, as we set up shop near each other in the media room.

ADVERTISEMENT

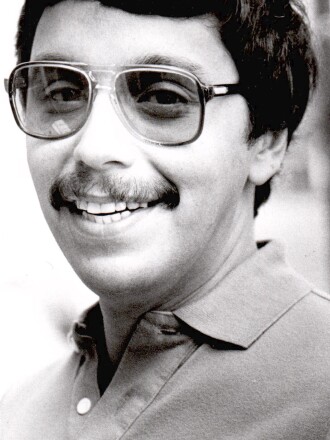

Understanding my Princeton connection with Dorr — a good friend of Reusse's — the sports columnist quickly pivoted to mention Casey Ramirez.

The mystery man, Casey Ramirez.

Ramirez arrived in my hometown in the early 1980s. He showered the town with cash. Why? One could only suspect. Where did his money come from? No one really knew at the time, though not many thought Casey’s generosity was simply in good faith, either.

Dorr, the longtime newspaperman in Princeton, died in September 2023. I worked with Dorr as his Union-Eagle intern in 1991 and had several discussions with him about Ramirez, the man people knew so little about yet had a past that was virtually nonexistent.

While the city of Princeton and its mayor tied their futures to the mystery man, Dorr never bought into the hype. He struggled, like much of the state and even national press, to pin down exactly why Ramirez was planting palm trees at city hall, helping fund a hockey arena, leasing those light-blue Volkswagen Rabbits to the city for $1 to use as squad cars and taking an entire senior living complex out to dinner, perhaps more than once.

As kids, we had a running joke that those VW Rabbits topped out at 50 mph, so any pursuit was pointless.

ADVERTISEMENT

Meanwhile, during this cash shower, Ramirez helped upgrade the city’s small airport to handle larger aircraft.

Something smelled fishy, but when you’re in elementary school and the internet is still some 15 years away, you leave it to the adults to figure out what’s going on. And the feds for that matter.

Ramirez had cash. A small town coming off the high inflation of the 1970s didn’t seem to turn its back to the green stuff. Ramirez was charming when you bumped into him. Rumors floated that he was flipping $100 bills to pay for purchases at the nine-hole golf course with $10 green fees or, as we believed, throwing out the occasional Benjamin with the candy during a city parade.

I didn’t see any $100s in my loot. Neither did my friends.

You really didn’t know the truth. Of course, there was growing concern he was involved in illegal activities, but either none of the cityfolk cared or Ramirez would simply deflect those questions. When WCCO-TV brought its I-Team to town to investigate, the evening news was a must watch.

Ramirez’s generosity spanned all ages. During a school field trip in the early ’80s to the then-downtown Dairy Queen, a few of us elementary-aged kids spotted Ramirez walking out of a bank next door. We wanted the guy’s autograph.

We approached Ramirez, who turned down our requests. Instead, he invited us kids to the airport that coming Saturday. Casey was going to give us a helicopter ride, something that he did at times for residents.

ADVERTISEMENT

I had never flown before, so this was a big deal. That next morning, my grandparents came to visit from their farm just outside of town. We asked them to join my mom and I to watch their grandson get a ride from the money man.

As other classmates arrived to take Ramirez up on his offer, Casey, in his ever-charming self, invited my mom and my grandparents too into this deluxe chopper. With four Beers in the air, we pointed out the city’s landmarks from high above. ��������, my great-grandparents’ laundromat, golf course, our home. Nonetheless, thrilling.

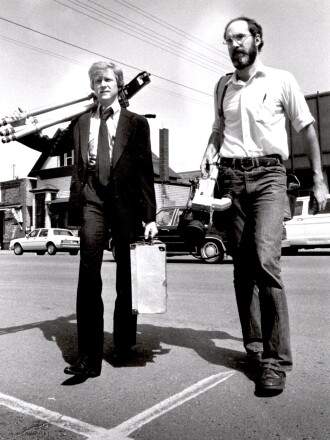

Dorr, I know, was frustrated early on, trying to find exactly who this man was. While Ramirez appeared in the Union-Eagle many times for his civic outpouring, the newspaper continued to find out the real story.

Then Ramirez got caught.

He did time.

About 15 years ago I pondered writing a book, but living 200 miles from sources would have made it difficult. In the summer of 2018, I heard Ramirez had at some point returned to the work force in east-central Minnesota. The juices flowed again.

Two summers ago, I stopped in at the Mille Lacs County Historical Society, a place that hasn’t changed much since I was last there in 1991. Surprised, yet totally unsurprised, there was no Casey Ramirez display or anything depicting that era in plain sight. It’s not the city’s bragging point, that’s for sure.

ADVERTISEMENT

“What do you have on Casey here?” I asked a few of the workers, poking my head into the office. Of course, you say Casey in Princeton, everyone knows who you’re talking about.

“Get the Casey file,” one woman said to another, who then reached into a back cabinet to pull out a heaping, oversized folder.

Inside, headlines screamed “Mystery Man,” “City benefactor” and everything in between.

I kept thinking, if I was a reporter back in those days, what could I have found out about Ramirez? What did those top-notch reporters from various local and national publications find out then? I sat and read for an hour, fascinated, yet stonewalled. Ramirez’s stories and the news articles about his wealth always had a different twist.

Returning this gem of a folder, the workers and I began talking. One woman, from Cambridge, recalled those residents being incredulous to what was happening in the town 20 miles to the west.

Suckers!

It’s all old news and dare you utter the syllable “Cas--” today, most Princetonians will shut you down. People want to forget.

ADVERTISEMENT

The museum workers did mention, however, there was still a palm tree in town.

“Where?” I asked, enthusiastically.

Sure enough, if you travel north on Highway 169 to the edge of town, there was a palm tree in a large planter outside a business. This May, it was moved to another location.

Ramirez was convicted in 1984 of conspiring to smuggle cocaine and income tax evasion. Despite various attempts by colleague Jeremy Fugleberg to contact Ramirez for this series, he did not oblige. He just may have moved on. The city certainly has.

You can still dig up on the internet, among other articles. A circa 1992 episode of “Top Cops” completely butchered the story in a reenactment. Pro-tip: Princeton does not have mountains.

But it does have its memories.