This is Part 4 of the Minnesota Vice series.

MINNEAPOLIS ŌĆö Don Shelby felt like a shell of himself.

ADVERTISEMENT

By all rights, February 1982 should have been a proud moment for him. Shelby, an investigative reporter for WCCO-TV in Minneapolis, had just aired a bombshell report that for sexual misconduct.

ShelbyŌĆÖs report would earn him and his investigative team, the ŌĆ£I-Team,ŌĆØ national praise, and it would result in WintonŌĆÖs confession and later that year.

ŌĆ£I knew how to investigate, I knew how to do all that stuff, but I was doing it all for me, to become recognized,ŌĆØ Shelby said, in his resonant voice now familiar to generations of news-watching Minnesotans, in a recent interview. ŌĆ£It didnŌĆÖt make me reckless ŌĆö it made me a little hard.ŌĆØ

Yet Shelby had met his match with the Winton story. He had, the week before it aired, decided to not do it, he said.

But WCCO-TV news director Ron Handberg, who had hired Shelby, nixed that idea.

ŌĆ£He said, ŌĆśThis information you've collected doesn't belong to you. It doesn't belong to me, it doesn't belong to CBS ŌĆö it belongs to the people.ŌĆÖ And my life changed,ŌĆØ Shelby said. ŌĆ£My career changed at that notion that I wasn't important, the facts were important, and the people had the right to the information that I had gathered.ŌĆØ

The Winton report aired, but Shelby, and his admittedly sizable ego, had been shaken. That and the long, exhausting year spent investigating Winton earned Shelby the enmity of a lot of friends in the legal profession.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many felt like Shelby and WCCO had convicted Winton before the judge got his day in court.

It all had taken an emotional toll. Shelby was spent.

ŌĆ£In fact, I felt like I wanted to quit journalism after that story,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£So I was in a mess.ŌĆØ

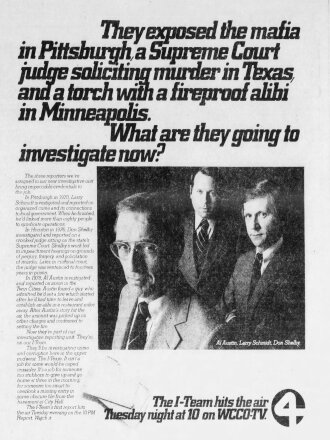

He was hoping to take something of a break while other reporters on his I-Team ŌĆö Al Austin and Larry Schmidt ŌĆö took the lead on a few stories.

The thing was, their stories were falling through. Shelby had to come up with something.

It would be both personally and professionally embarrassing if the team didnŌĆÖt have a story in the expected slot in late May 1982.

The I-Team, which Shelby had co-created in 1980, two years after arriving at WCCO in 1978, was committed to producing four investigative reports a year, ones that would guaranteed to raise a stir.

ADVERTISEMENT

ŌĆ£You gotta have that blood in your mouth,ŌĆØ at the time, showcasing his flair for the dramatic phrase. ŌĆ£Dig and chew and never let go.ŌĆØ

The I-TeamŌĆÖs stories would air during sweeps weeks, the four times a year when TV station audiences are closely measured, so stations broadcast their best programming to attract more viewers.

The I-TeamŌĆÖs work was tailor-made for sweeps weeks, wave-making investigative reporting from a newsroom already well-known for hard-hitting journalism.

Shelby went to his "tickler file" of story ideas. There was one in there that seemed like it was doable in time for the May slot.

It was something WCCO reporter Dave Nimmer and photojournalist Bob Manary had told him about a guy named Casey Ramirez, up in Princeton, Minnesota, spending a lot of money and buying a lot of influence in that small town. Something about police cars and palm trees?

That was it.

Now the I-Team needed to hustle to get the Ramirez story, from nearly scratch, in a few short months.

ADVERTISEMENT

To Shelby, it felt almost like a fresh start.

ŌĆ£Right before Casey, when I was (covering) Winton, thatŌĆÖs when I became a journalist,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£So I went into the Casey investigation as a journalist. I was a showboat prior to that.ŌĆØ

MARCH 1982 ŌĆō WCCO newsroom, Minneapolis

The first order of business for the I-Team: Get all the documents on Ramirez.

Reporters today can often glean reams of information from a simple internet search. In 1981 gathering the same took good, old-fashioned shoe-leather journalism, or rather, a lot of airline tickets.

ŌĆ£We have to be in Phoenix, we have to be in Miami, we have to be in Panama City, we have to be in Turks and Caicos. We have to be everywhere,ŌĆØ Shelby said. ŌĆ£We have to pull all these documents, but there's no internet, and you can't be specific because you don't know what you're looking for exactly, right?ŌĆØ

Schmidt got a plane, destination everywhere.

ŌĆ£He stayed on a plane for 17 days, and it cost $600,000 ... just in travel expenses and printing expenses,ŌĆØ Shelby said. (Nearly $2 million in 2025 dollars.)

ADVERTISEMENT

Then the sorting began. Piece by piece, the I-Team was assembling a picture of Ramirez. In their reporting, they also shook loose some documents from federal investigations, including a Customs report documenting how Ramirez was fined after he reported a false hijacking in 1978 to evade surveillance and likely smuggle people into Florida.

What they were finding all made for quite a story ŌĆö a small Minnesota town corrupted by a mysterious but flamboyant outsider.

ŌĆ£It was just a delicious story to start with,ŌĆØ Shelby said. ŌĆ£This story was just unbelievable.ŌĆØ

Shelby was no stranger to small town shenanigans. He had grown up in a small town of Royerton, Indiana, just outside of Muncie, Indiana, which had been It had also once been known as ŌĆ£Little ChicagoŌĆØ and had a long history of corruption and dirty politics.

In previous jobs at stations in Texas and elsewhere, Shelby had covered the mob and made connections in the world of organized crime.

ŌĆ£So I knew how corruption worked,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£I knew because I saw it firsthand, and how you could manipulate the government to benefit a few as opposed to the many.ŌĆØ

The palm trees. The police cars. Taking folks from the retirement home out to dinner. Expanding the airport. Palling around with the mayor. Bankrolling a youth hockey arena.

ADVERTISEMENT

It all smelled of corruption.

ŌĆ£He is just corrupting everyone he seesŌĆ”ingratiating himself into every conceivable nook and cranny of that community, and in doing so, corrupting people,ŌĆØ Shelby said. ŌĆ£But genius work ŌĆö he was a genius. He had it figured out.ŌĆØ

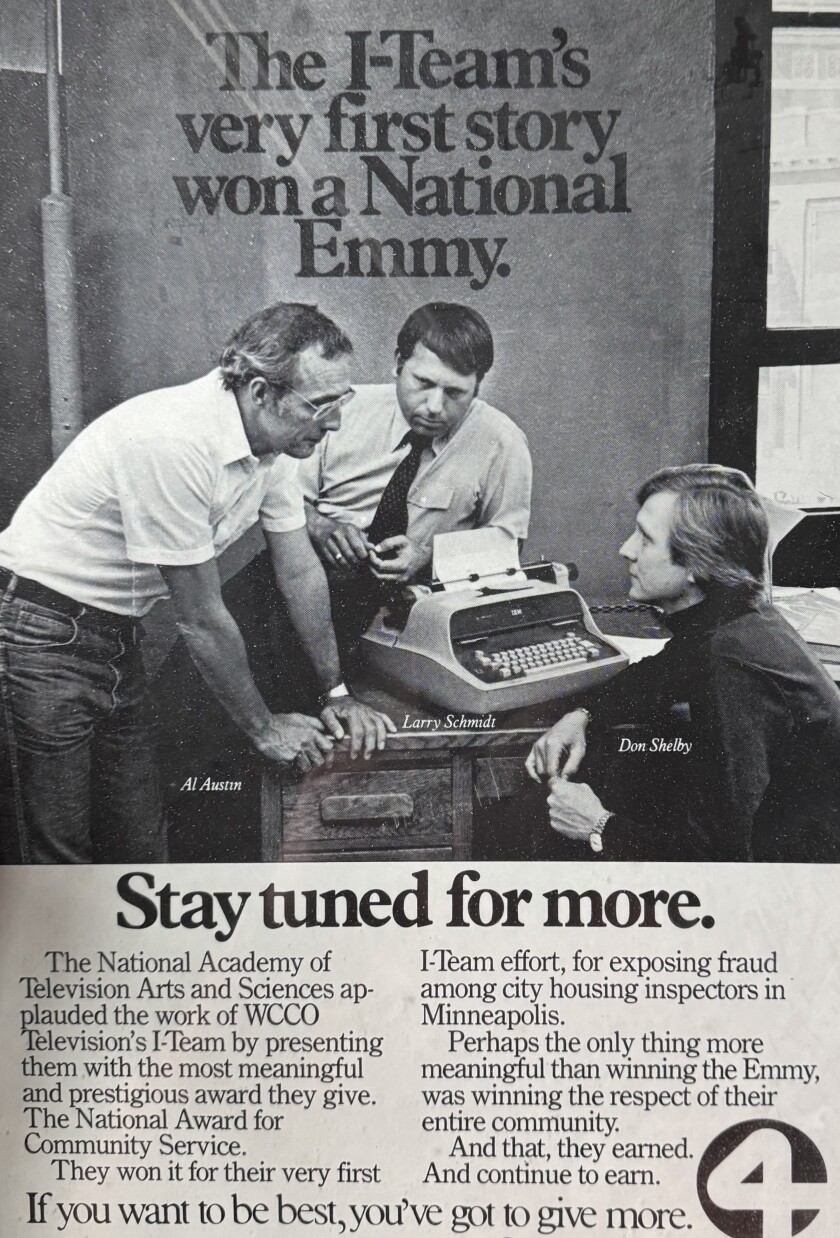

MID-APRIL 1982 - Princess Hotel, Acapulco, Mexico

Bob Manary watched Casey RamirezŌĆÖs window in the Princess Hotel. Behind the window curtain, many people came and went. From his balcony, Manary couldnŌĆÖt tell who they were.

Interesting. Manary made a note.

Manary, the WCCO photojournalist, had flown to Acapulco ŌĆö on Mexico's Pacific coast south of Mexico City ŌĆö to gather more information on Ramirez.

He had told Ramirez he hoped to do another story about him, a feel-good piece about PrincetonŌĆÖs growth.

Apparently he hoped to contribute to ShelbyŌĆÖs ongoing I-Team investigation, even though, according to Shelby, he wasnŌĆÖt involved in it directly, nor was Shelby aware he was in Mexico (In a recent interview, Manary disagreed on this point).

But Princeton was ManaryŌĆÖs hometown, and he had doggedly stayed on the Ramirez story ever since he first interviewed the man a year prior, in April 1981.

He had stayed in touch with the DEA too, including special agent Michele Leonhart, protecting her identity by marking her name as ŌĆ£MŌĆØ and "Lady" in his scrawled notes on the case.

Manary carefully made notes of RamirezŌĆÖs actions around the hotel. On Friday night, at the hotel's Laguna Bar, he noted: ŌĆ£Casey says heŌĆÖs been to Colombia in the past month ... 'I got to lay low for about three months,'" he quoted Ramirez as saying.

He noted the ŌĆ£lotsŌĆØ of stamps in RamirezŌĆÖs passport, and asked him about his girlfriend, Pam Jackson, whom Ramirez called P.J., wondering if she liked living in Princeton.

ŌĆ£P.J. likes the community. She gets to travel, but itŌĆÖs like Peyton Place (there). She doesnŌĆÖt like that,ŌĆÖŌĆØ Ramirez said, per ManaryŌĆÖs notes, mentioning about a small town with deep secrets.

ŌĆ£My job was to get as many pictures of Casey as I could,ŌĆØ Manary wrote in later written recollections about Princeton and Ramirez. ŌĆ£We went horseback riding in the surf and parasailing the next morning. I got my pictures.ŌĆØ

In one video shot taken by Manary, Ramirez approaches a man and introduces himself in Spanish as ŌĆ£Diego.ŌĆØ

Manary later made sure that videotaped moment got to Shelby, who said he was surprised to find out Manary had also been chasing ShelbyŌĆÖs quarry this whole time.

Shelby wasn't happy. But he did incorporate ManaryŌĆÖs footage into the final cut of the I-Team investigation.

The I-Team's big four-part series was ready to air during the upcoming sweeps week, starting on Monday, May 24.

THE WEEKEND OF MAY 22-23, 1982 - Princeton

The mood in Princeton in late May was tense. The I-Team reporters werenŌĆÖt the only journalists chasing the Ramirez story and it was causing Princeton some real heartburn.

On Saturday, May 22, 1982, the St. Cloud Times ran a pair of front page stories: ŌĆ£Princeton turns shy in spotlightŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Who is PrincetonŌĆÖs mysterious benefactor?ŌĆØ

The Times noted that Princeton was ŌĆ£close-mouthedŌĆØ and ŌĆ£skittishŌĆØ when it came to discussing Ramirez. Mayor Richard Anderson had checked himself into the hospital with stomach trouble. Police Chief Tom McCarthy had taken the week off work to ŌĆ£tinker in his garage.ŌĆØ

Ramirez seems to have made himself relatively scarce, as well. The Princeton paper had already reported: Ramirez had already stepped down from his seat on the Airport Commission, with a letter from his attorney saying the role was ŌĆ£jeopardizing his personal and family life and his privacy.ŌĆØ

The Times quoted Jerry Davis, the youth hockey booster and one-time manager of the Princeton Co-op Credit Union, who would later be found guilty of several felony counts for not reporting RamirezŌĆÖs big cash deposits. He had recently resigned from the job and was now manager of the youth hockey arena bankrolled by Ramirez.

Davis pooh-poohed the talk about Ramirez and his activities.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs all just small-town rumors,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£The first thing when I resigned from the credit union, someone came up to me and said, ŌĆśHey, I heard you embezzled some money.ŌĆÖ You donŌĆÖt pay attention to small-town rumors.ŌĆØ

The Minneapolis Star and Tribune published a front-page package on Ramirez the next day. It had some of the details about Ramirez the WCCO team would soon air, but not everything.

Still, there were very interesting nuggets.

Ramirez had first lived in, then purchased Mayor Richard AndersonŌĆÖs house, the reporting noted. The house's indoor pool was ringed by palm trees, the ones from city hall, but brought in for the winter.

The article also described how Ramirez had once taken residents of the Elim Home, a retirement home in Princeton, out for dinner at The Farm Supper Club. Dolly Fairchild, formerly PrincetonŌĆÖs city clerk, was effusive in her praise of Ramirez as she discussed the event.

ŌĆ£He thanked the old people for coming, for letting him take them to dinner. He said it was a privilege for him because they were the backbone of Princeton, the people who had helped build the town,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£He didnŌĆÖt talk for long, but nearly everyone was crying when he got through.

ŌĆ£Casey is good for Princeton. HeŌĆÖs exciting. HeŌĆÖs alive. He loves people and he wants to do things to help them.ŌĆØ

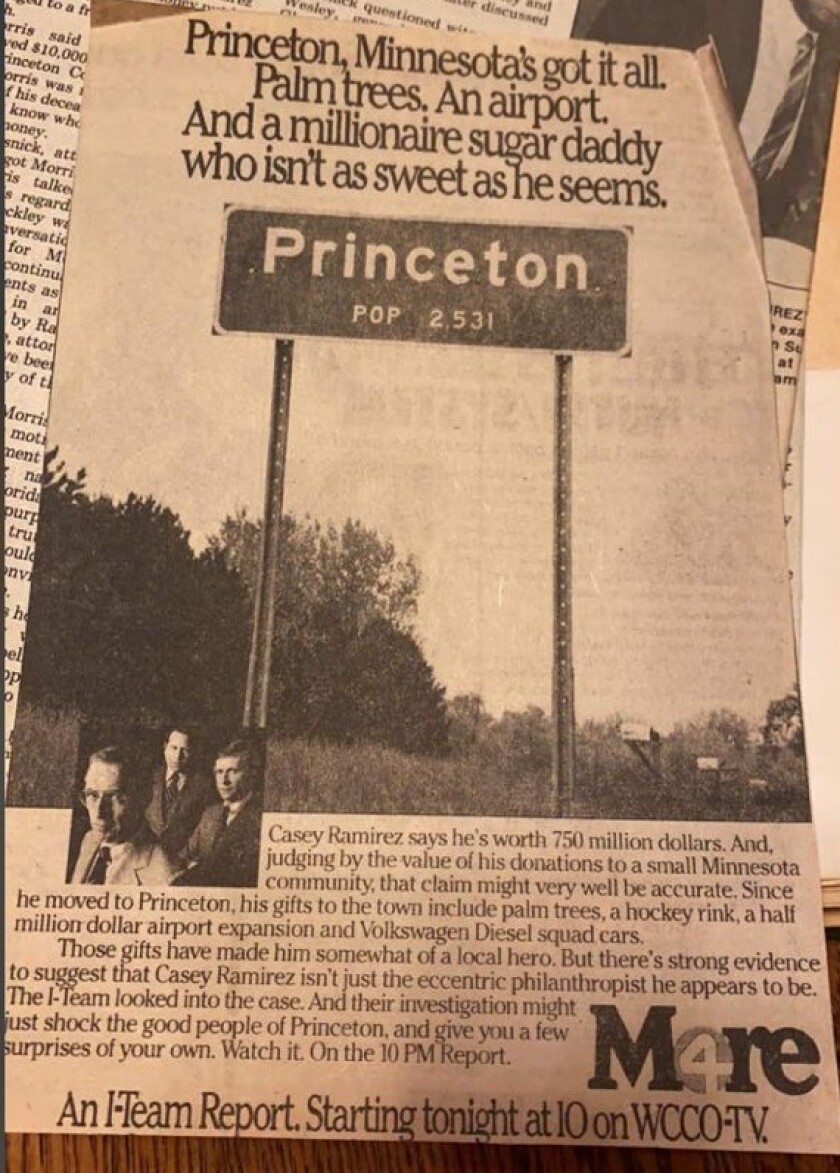

WCCO paid for a large newspaper ad promoting the upcoming I-Team report. It prominently featured PrincetonŌĆÖs town sign, and the words: ŌĆ£Princeton, MinnesotaŌĆÖs got it all. Palm trees. An airport. And a millionaire sugar daddy who isnŌĆÖt as sweet as he seems.ŌĆØ

MAY 24, 1982 ŌĆō Princeton City Hall

The next day, on Monday, Mayor Richard Anderson called a special meeting of the Princeton City Council to order.

It was noon on May 24, 1982. The subject: Casey Ramirez.

Things were tense in the wood-paneled room. Everyone knew about the WCCO I-Team report that was going to start airing that night.

Joel Stottrup, the Princeton Union-Eagle newspaper reporter, was there too.

The council's first order of business was to ban Stottrup from taking any photos ŌĆö a request from Casey Ramirez, as a condition for him to attend. He had actually requested the special meeting, to address any questions about the I-Team report.

The no-photos vote was unanimous, demanding the reporter put his camera away. There would be no photos at this public meeting of a body of public officials. Anderson warned Stottrup police would enforce the restriction.

Once present, Ramirez informed the city council the WCCO I-Team report, which was due to air later that evening, was "sensationalism and he was 'really hurt about it,'ŌĆØ Stottrup reported.

All of his giving to the city and its people came with no strings attached, Ramirez insisted.

He seemed wounded.

ŌĆ£You (the city) were running into deficits and I came along,ŌĆØ he said, according to Stottrup's reporting of the meeting.

Some city council members asked Ramirez to put some commitments about the airport in writing, or seek a letter of financial ability.

Ramirez declined both. It was an pair of unusually unfriendly requests.

There was another blow to Ramirez that day. The Princeton Civic Betterment Club had voted 25-5 against Ramirez's request to put palm trees up and down LaGrande Avenue.

While town officials appeared to still be in RamirezŌĆÖs corner, the media attention was taking a toll. There seemed to be growing skepticism in Princeton about Ramirez and his plans.

THAT NIGHT ŌĆō WCCO TV, Channel 4

The at 10 p.m. that night exploded across Minnesota. Its biggest boom was felt in Princeton.

The camera slowly zoomed in on Shelby. The monitor next to him showed a freeze frame of a tousled-hair Casey Ramirez, wearing a blue polo shirt, palm trees in the background. It was one of Bob ManaryŌĆÖs shots from Mexico.

ŌĆ£Several years ago, Casey Ramirez arrived in Princeton. He was warmly received by the people there,ŌĆØ Shelby said. ŌĆ£In return, Casey has done a lot for Princeton ŌĆö heŌĆÖs spent a lot of money. Casey claims heŌĆÖs worth $750 million, right up there with the Rockefellers."

Shelby tilted his head slightly.

ŌĆ£Yet no one seems to know much about him, and thatŌĆÖs exactly the way Casey wants it.ŌĆØ

The Ramirez investigation aired one segment a night, which meant Shelby wrapped it up on Thursday.

Shelby revealed that Davis, the credit union manager hadn't simply left his job for health reasons or to work at the Ramirez-bankrolled hockey arena.

In fact, Davis had himself, as credit union manager, signed off on what was essentially a letter of credit for construction the hockey arena without informing the credit union's board of directors

That meant the credit union refused to pay a contractor when the bill came due. Ramirez himself had to fly in bags of cash to pay the $128,360 billŌĆöin $20 bills.

The I-Team also revealed Ramirez was under investigation by federal and state law enforcement. It showed he operated a number of aliases ŌĆö among them Dr. Ramirez, Casey Jackson, Mike Chambers, Dr. Diego, John Key, George King and Dr. Casey.

None of RamirezŌĆÖs claims about where he got his wealth checked out, Shelby said. He wasnŌĆÖt a major stockholder of Apple Computers. He hadnŌĆÖt gotten a patent for any invention. He wasnŌĆÖt a director of Republic Airlines, an owner of airplane companies or an inheritor of large wealth.

In the final broadcast, Shelby described Princeton as a small town caught in a tangled web from ŌĆ£a man who deals in lies.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£This has not been an ordinary story of corruption. The people of Princeton, caught up in CaseyŌĆÖs ventures are, so far as we can tell, honest, trusting people ŌĆö nice people.ŌĆØ

Shelby smiled slightly.

ŌĆ£They believe, some still do, that CaseyŌĆÖs gifts were good for the town. But the gifts have come at a cost to Princeton,ŌĆØ he solemnly intoned. ŌĆ£Princeton will emerge from the Casey crisis intact, no doubt, a little wiser than before and a little sadder. And the rest of us are left to wonder how we would act if Casey had come to our town.ŌĆØ

***

Many in Princeton were not impressed with the I-Team's reporting and its conclusions, even if some of them agreed with it. Some flew to the townŌĆÖs own defense.

ŌĆ£I find it highly distasteful to have the ŌĆśtruthŌĆÖ rammed down my throat by big-city reporters condescending to help the poor, dumb hoe-handles up north get their facts straight,ŌĆØ wrote one resident in a letter to the Princeton Union-Eagle.

The Union-Eagle, for its part, was unsparing in its criticism of Mayor Richard Anderson and the Princeton City Council after the WCCO report. The I-Team's revelations had unearthed damning information.

"It seems to us that the mayor and the council may experience the greatest embarrassment for accepting so much, and being party to so many transactions, even making out receipts to an alias, without really knowing with whom they are dealing,ŌĆØ the unsigned editorial said. ŌĆ£It is one thing for a private citizen to accept favors but quite another for public officials to do so."

Ramirez struck back. He ran a mocking ad in a Minneapolis newspaper featuring a handdrawn image. It showed Shelby ramming his foot into his mouth and a mustachioed photographer, possibly Manary, staring at him in befuddlement.

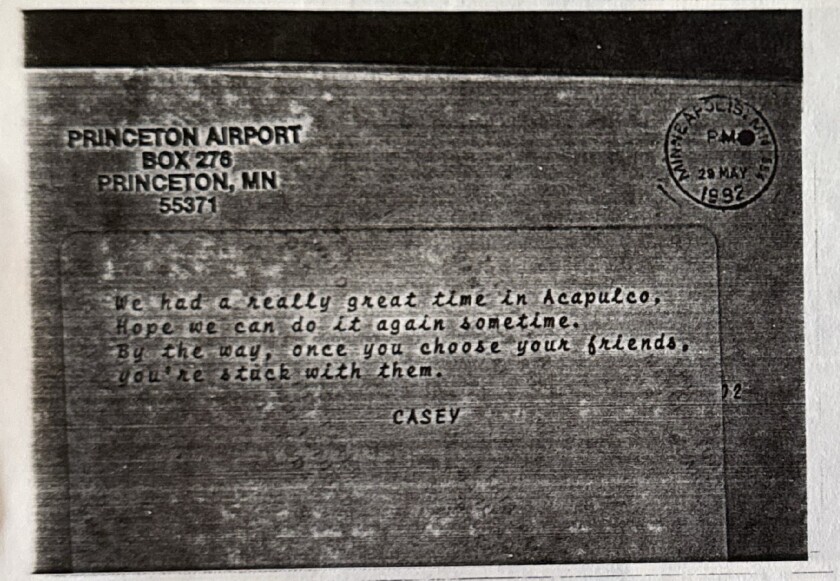

Manary received a postcard, addressed from the Princeton airport, RamirezŌĆÖs home base, reading: ŌĆ£We had a really great time in Acapulco. Hope we can do it again sometime. By the way, once you choose your friends, youŌĆÖre stuck with them.ŌĆØ

It was signed, simply, ŌĆ£Casey.ŌĆØ

Ramirez also ran a large advertisement in a Princeton shopper publication, a full-page ad with clip art of palm trees in the corner, that read:

ŌĆ£To all the people of the Princeton area ... who have had their daily routine interrupted by outside interests, I offer a special thank you for taking much of the excitement in stride, knowing full well that what makes good copy in a story does not necessarily make it right! Now maybe we can get back to the business of running our own lives again. With warmest regards, Casey.ŌĆØ

Many in Princeton still sprung to his defense, and the city council still seemed willing to work with Ramirez ŌĆö even accepting gifts from him.

Soon after the I-Team report aired, Ramirez told town officials that going forward, his donations would be made anonymously ŌĆö although everyone would still know who made them.

Then, coincidentally, the city council happened to be offered two 1982 diesel Oldsmobile Cutlasses for the Princeton Police Department, under a $1 a car two-year annual lease from Odegard Motors, with the costs otherwise covered by an anonymous donor.

The council decided it couldnŌĆÖt find any harm in accepting the offer.

The donor was anonymous, after all.

***

At the Minneapolis DEA office, the team investigating Ramirez was frustrated by the I-Team report.

They had known it was coming, and talked to Shelby before it aired, telling him it could potentially harm the investigation.

Shelby disagreed.

ŌĆ£Don Shelby told [DEA Minneapolis office chief] Jim Braseth that, ŌĆśYouŌĆÖre going to get more informants and more information once we air this than youŌĆÖll ever need,ŌĆØ said John Boulger, on the DEA task force investigating Ramirez, in a recent interview.

ŌĆ£After it aired, my recollection is we got one call from someone in a mental institution. That was it. That was the whole extent of what was promised, or what we got from it,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£It drove everyone underground. It was not at all helpful.ŌĆØ

And for Ramirez?

ŌĆ£I didnŌĆÖt slow him down a bit.ŌĆØ

Ramirez wasn't done publicly mocking the I-Team's report about him.

At the the townŌĆÖs annual Rum River Festival parade in June, Casey dressed up like a clown, painted dollar signs on his cheek and drove a manure spreader he labeled ŌĆ£I-Team,ŌĆØ throwing out candy filled paper bags stamped with the words ŌĆ£CaseyŌĆÖs Brown Paper BagŌĆØ and a dollar sign.

ŌĆ£And, somehow, that entry in the parade got a first-place award,ŌĆØ wrote Luther Dorr, editor of the Princeton newspaper.

Dorr noted that despite all of the furor, Casey hadnŌĆÖt done one key thing ŌĆö deny much of anything (He had rejected a meeting with the newspaper).

Ramirez did give an interview to a newspaper he likely figured was much more sympathetic: the Mille Lacs Messenger, the weekly newspaper in Isle, Minnesota, a small town on Lake Mille Lacs, about 50 miles north of Princeton.

After the WCCO report, the Messenger had printed an unsigned editorial calling the I-Team the ŌĆ£Innuendo Team.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Whether Casey is guilty of anything is not WCCOŌĆÖs business,ŌĆØ the editorial said. ŌĆ£He was tried by a jury of his smears!ŌĆØ

Jay Andersen, editor of the weekly newspaper ostensibly interviewed Ramirez because he was seeking to do in Isle what he had done in Princeton: upgrade the local airport and use it as a base of operations.

In his interview with Andersen published July 8, 1982, Ramirez had a lot to say about the I-TeamŌĆÖs report.

ŌĆ£They made me the Jesse James of Princeton and I havenŌĆÖt done any harm to anyone. IŌĆÖm really disappointed that they mentioned drugs or white slavery and that ŌĆ” thatŌĆÖs a cheap shot,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£Some things I donŌĆÖt deny, if you can ask me a direct question, if I can answer you, I will.ŌĆØ

He then refused to answer direct questions about the source of his money.

A few weeks later, Shelby responded with a broadside of a letter to the editor, essentially answering the MessengerŌĆÖs editorial. He laid out the I-TeamŌĆÖs approach and what it found on Ramirez, and then closed with a warning.

ŌĆ£When Casey runs, which is predicted, he will leave Princeton holding a very large bag,ŌĆØ he wrote. ŌĆ£We thought it was important to get these facts out to the Princeton people not to increase our ratings but to get the facts to them before they made themselves further victims of Casey. ŌĆ” We couldnŌĆÖt in conscience remain silent while the city continued to accept RamirezŌĆÖs lies and promises absent of the true facts.ŌĆØ

"I will go to my grave knowing that we performed a necessary service," Shelby concluded (italics in the original).

SUMMER/FALL/WINTER 1982 - Princeton

In Princeton, despite everything, city leaders still seemed to accept what Ramirez had told them them.

Some even had a bit of fun with it.

In June the city council accepted the gift of a new airport beacon from Ramirez. But the council did require a written application for a fly-in he wanted to host at the airport in September.

In mid-July, with application in hand, the Princeton Airport Commission signed off on RamirezŌĆÖs plans for the fly-in.

In the meeting, Commissioner Dick Nelles was paraphrased as saying, ŌĆ£there was a lot of money the state didn't have to spend [on the airport] because of donations from John Key,ŌĆØ wrote Joel Stottrup, the Princeton Union-Eagle reporter.

ŌĆ£Nelles was asked after the meeting who John Key was and he answered he was only making fun of the alias names tacked onto Casey Ramirez during the recent WCCO I-Team report on Ramirez," Stottrup wrote.

Two hundred and sixty aircraft flew into Princeton for the fly-in.

Ramirez continue his public demonstrations of affection. In late September, he took 150 Elim Home residents and 40 people from the Oaks affordable-housing apartments out to dinner at the Sunset Ridge Supper Club.

That year, Anderson decided not to run for mayor, after nine years in office. He later touted the expanded airport as a signature achievement in a profile written by Joel Stottrup, the Princeton Union-Eagle reporter.

Asked about Ramirez and the WCCO report, which questioned why the city council hadnŌĆÖt questioned Ramirez more before accepting donations, Anderson struck back.

ŌĆ£AndersonŌĆÖs answer to the inquiry was that Ramirez was judged without sufficient evidence and that he could see no possible gain for Ramirez in any of his donations,ŌĆØ Stottrup wrote.

Instead Casey ran for mayor, as a last-minute write-in candidate. He ran a large print advertisement touting himself as a candidate for ŌĆ£managing mayorŌĆØ ŌĆö ŌĆ£Your choice. Your voice,ŌĆØ it read.

He printed 150 posters and 1,500 flyers and distributed them the week prior to the vote. He got 109 votes out of a total of 1,409.

Yet despite his low electoral turnout, and some rumbles of dissent, PrincetonŌĆÖs leadership seemed still in step with Ramirez.

Fresh off his electoral defeat, Ramirez ŌĆö wearing a cowboy hat ŌĆö cut the ribbon on the new Princeton Youth Hockey Arena. There was a buffet lunch for the hundreds who attended and Richard Dwyer, a professional skater, gave two performances.

Asked who paid for everything, arena manager Jerry Davis, formerly of the Princeton Co-op Credit Union, demurred, saying he didnŌĆÖt know.

As 1983 dawned, Ramirez launched a surprise salvo of New YearŌĆÖs Eve fireworks from the city airport.

At its first meeting of the year, the city council agreed 3-2 to buy advertisements declaring Princeton as ŌĆ£Home of the Northern Palms.ŌĆØ

That had all been CaseyŌĆÖs idea.

His friend, Mayor Richard Anderson, cast the decisive vote.

But no amount of support from Princeton city leaders could shield him from what was about to happen in far-off Florida ŌĆö and The Bahamas.

<<< Read Part 3

Read Part 4 >>>

Follow the series

Notes: This article is based on interviews for this article with Boulger, Leonhart, Manary, Nimmer and Shelby, as well as ManaryŌĆÖs contemporaneous reporting notes from 1981-1983 and his 1992 recollection column given to Princeton native Kevin Odegard, the Oct. 22, 2009, Minnesota Monthly article clips of WCCO news microfilmed copies of the Isle, Minnesota, and Princeton, Minnesota newspapers housed in the collections of the in St. Paul, the personal collection of Kevin Odegard, Princeton Union-Eagle photos and clippings and Ramirez items archived by the in Princeton, and coverage of Ramirez by various Minnesota newspapers archived on Anderson and Ramirez never responded to multiple interview requests. Davis and Stottrup declined to be interviewed. Deceased are Austin (2018), Dorr (2023), McCarthy (2011), Nelles (2020) and chmidt (1998).