This is Part 3 of the Minnesota Vice series.

PRINCETON, Minn.ŌĆö Ed Fisk had questions. And subpoenas.

ADVERTISEMENT

It was late 1981, and the IRS agent was in Princeton, investigating a mysterious newcomer named Casey Ramirez.

Ramirez had been throwing around tens of thousands of dollars on town projects, had practically taken over the airport and appeared to be close pals with the mayor.

Fisk had checked: Ramirez hadn't filed a tax return in years. So the IRS investigator turned to RamirezŌĆÖs financial accounts in Princeton. What he found at the small Princeton Co-op Credit Union raised alarm bells.

Between Oct. 6, 1980, and Aug. 31, 1981, the credit union records showed it had accepted cash deposits from Ramirez totaling $962,256 (about $3 million in 2025 dollars).

This was no small-time piggy bank. It was a significant chunk of the credit union's total assets.

It also came with requirements.

ŌĆ£We went in there because we knew that if you had more than a $10,000 cash deposit, the bank or credit union would have to report it on a form to the IRS,ŌĆØ Fisk said in a recent interview. ŌĆ£And we knew that there was more than $10,000 going through there.ŌĆØ

ADVERTISEMENT

Nearly a million dollars in Ramirez's cash had flowed into the credit union without its staff ringing the alarm bells, the ones that would inform the IRS of unusual deposits. Now that was worth investigating further.

At the credit union, Fisk found several women who were deeply concerned about what had been going on there, all at the behest of manager Jerry Davis.

ŌĆ£They were very, very cooperative, and they were pretty much upset with Jerry Davis,ŌĆØ Fisk said.

What they told him would become crucial evidence against Davis, and later, Ramirez.

MAY 1980 - Princeton Co-op Credit Union

Teller Sue Johnson was manning the counter of the Princeton Co-op Credit Union on May 15, 1980.

That's when she got a deposit from Casey Ramirez, $80,000 in cash (about $310,000 in 2025 dollars).

For Princeton, this was an eye-popping amount.

ADVERTISEMENT

Johnson had worked at a Minneapolis bank. Something in her memory bothered her. DidnŌĆÖt that big of an amount come with reporting requirements?

Johnson was correct. a report be filed for any cash deposit over $10,000, something known as a Currency Transaction Report, meant to catch money laundering and other nefarious banking purposes.

Legitimate businesses donŌĆÖt often deal in large amounts of cash, but criminals do. Tracking big cash deposits can be a good way to catch crooks.

Johnson checked with her boss, Davis, the credit unionŌĆÖs bespectacled manager.

Did she need to file that report? She recalled that there were often differences in the paperwork banks and credit unions had to file. Was that the case here?

Davis hesitated, but finally answered.

ŌĆ£Yes, theyŌĆÖre different.ŌĆØ

ADVERTISEMENT

Essentially, no report needed to be filed.

RamirezŌĆÖs $80,000 was deposited, kept invisible to the authorities.

Another morning that same month, credit union cashier Joyce Edmonds got into work and opened the door to the vault.

There she beheld a big cardboard box. She opened up the box flaps. Inside she found about $300,000 (about $1 million in 2025 dollars).

It was an astounding stack of cash.

She had worked at the credit union for about 15 years. But this was something new.

It had to be Casey RamirezŌĆÖs cash, she decided. Only he deposited so much cash, and did it like this.

ADVERTISEMENT

And it wasnŌĆÖt uncommon for him to do this, either. So much money. No one else dealt in that amount of cash.

Nor would the credit union usually store cash like this. The usual procedure was to deposit it in the credit unionŌĆÖs accounts in Princeton State Bank across the street.

When Ramirez ŌĆö or his girlfriend Pamela ŌĆ£P.J.ŌĆØ Jackson or business associate Kent Moeckly ŌĆö arrived to deposit cash, Edmonds often stayed late to count all the money.

Ramirez and all this cash made her nervous. Sometimes there was too much for the filing cabinet where it was kept. Sometimes it was stacked in piles in the back, including on the floor.

This is not at all the normal way a financial institution does business.

Edmonds went to the hardware store and bought contact paper to cover the bank windows so people wouldnŌĆÖt see the money.

She asked Davis, her manager, what to do with Ramirez's cash.

ADVERTISEMENT

DonŌĆÖt deposit it all at once, he told her. In the mornings that followed the arrival of the cardboard box, Davis instructed Edmonds to do something unusual.

Each morning he would tell her when to deposit more of RamirezŌĆÖs cash, a bit more here, a bit more there, in RamirezŌĆÖs various accounts.

In the meantime the box of cash just sat there in the vault. Off the credit union's books.

Davis told Edmonds to use the box for daily operational cash for the credit union, to cover the ŌĆ£shared draftŌĆØ checks that were cashed that day.

It was basically a handy, off-the-books piggy bank.

ŌĆ£So we would take checks ŌĆö when the tellers needed money in their drawers, we would take from their drawers and replenish with the Ramirez money,ŌĆØ Edmonds later said.

Nobody was really keeping track. They knew it was RamirezŌĆÖs money. TheyŌĆÖd put the shared draft checks into the box, and take out cash to cover them.

No receipt. No reports. Nothing. Edmonds didnŌĆÖt like it.

This was, as Fisk knew, functionally money laundering. By blending RamirezŌĆÖs cash into the credit unionŌĆÖs drawers without logging or reporting it, the credit union was essentially masking Ramirez cash deposits, while building up his accounts and also keeping the credit unionŌĆÖs daily cash pool refreshed.

Laundered.

ŌĆ£So they were getting rid of his cash that way. How much they were able to get rid of that way, I don't know,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£The rest of it was probably picked up and paid to people in town that he had to pay for things.ŌĆØ

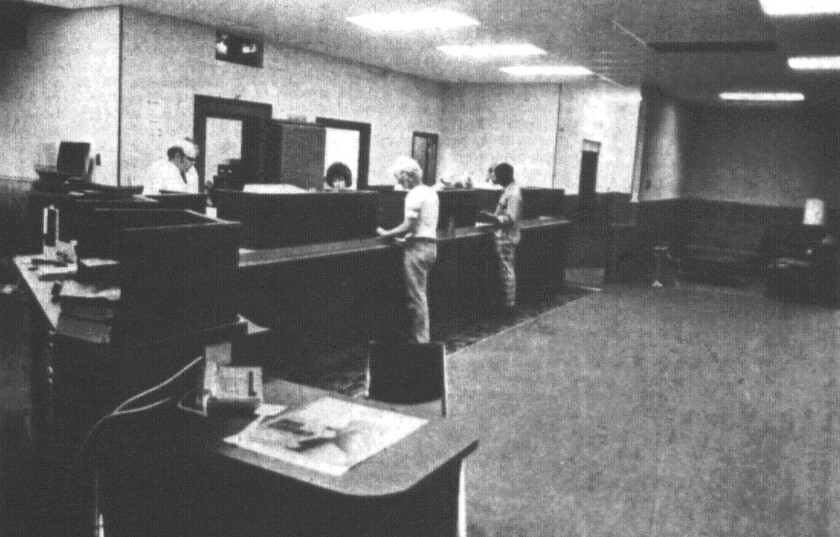

GROW, GROW, GROW - 1973 - Princeton Co-op Credit Union

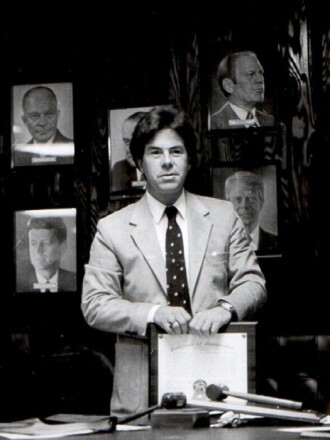

When Davis had been hired to the manager job by the Princeton Co-op Credit Union board seven years earlier in 1973, its goal had been clear: Build us up.

Davis got it done. The credit union, which had been founded in 1937, had $1.5 million in deposits in 1973. Davis doubled that amount, then over the next decade doubled it again to over $6 million.

This was largely due to something called shared drafts. Thanks to a 1976 state law, the credit union was newly able to offer these shared drafts ŌĆö essentially checks, just like those offered by banks.

In a flash, having an account at the credit union meant you could use checks drawn on your account for day-to-day expenses.

ŌĆ£The draft is part of our survival,ŌĆØ Davis told the Minneapolis Tribune after the new law was approved.

It did better than that. Davis had found the engine that would power the credit union to success.

In September 1977, Davis announced the credit union was building an addition that would near double its physical size.

HOCKEY DREAMS - 1977, Princeton ═ß═ß┬■╗Ł Board

Davis hadnŌĆÖt only been trying to build up the credit union that year. He had been trying to build Princeton into a youth hockey powerhouse (in 1977, this meant boys hockey).

Anyone who knew Davis could have told you: He loved youth hockey. He had been advocating for PrincetonŌĆÖs youth hockey program ŌĆö which had been founded in 1973 ŌĆö for years now.

In 1977 Davis and others from the Princeton Youth Hockey Association met with the Princeton ═ß═ß┬■╗Ł Board, to once again request a high school hockey program.

The number of kids involved in the Hockey Association had jumped from 60 to 160 in just four years.

ŌĆ£The number of kids involved indicate the support,ŌĆØ Davis told the school board.

Their request came at something of a pivot point for youth hockey in Minnesota.

Minnesota has loved hockey ever since it in the late 1800s. It was and is part of the stateŌĆÖs culture ŌĆö a cold-weather game, played on ice, a natural fit for a cold-weather state with its under-counted ŌĆ£10,000 lakes.ŌĆØ

Some local high school rivalries in Minnesota, such as now date back more than 100 years.

But hockey wasnŌĆÖt always a big youth sport statewide. While the first state youth hockey tourney it was dominated for decades by teams from big schools in the Twin Cities and from towns in northern Minnesota where kids were practically born wearing hockey skates.

But by the late ŌĆś70s, youth hockey was becoming a statewide phenomenon. More and more small communities like Princeton were looking to build up their youth hockey teams, and i Boosters like Jerry Davis were central to those efforts.

The same year the hockey boosters were asking the school district to start a youth hockey program, Davis met a newcomer in Princeton named Casey Ramirez.

Ramirez wasnŌĆÖt yet throwing money around Princeton but he left quite an impression on Davis, who was immediately taken with him.

Davis recalled later: ŌĆ£I met him and I wondered, am I privileged?ŌĆØ

THE LUCKY BREAK - 1980, Princeton

The newly expanded Princeton credit union opened in August 1978 just in time to greet a troubled economy.

Inflation was rising, economic activity stagnating, creating what became known as ŌĆ£stagflation.ŌĆØ

The Federal Reserve, under President Jimmy CarterŌĆÖs handpicked leader, Paul Volcker, tried to jolt the economy out of its malaise in 1979 by jacking up interest rates, making it generally more expensive for anyone to take out a loan.

VolckerŌĆÖs plan was to slow down the economy and thus cool inflation. He was betting that if the economy took a short-term hit, it would eventually rebound. It would later be called the "Volcker shock."

It was sort of like getting someone to sober up by kicking them in the face.

By 1980, when Greg Withers arrived at city hall as the new city administrator, VolckerŌĆÖs kick was hurting. A recession seemed to be on the horizon.

The economic concerns weighed on both local business leaders and youth hockey boosters eager to capitalize on a popular program.

PrincetonŌĆÖs hockey teams, without an ice arena, had to rent ice time at down the road to practice. Regardless, they were soon drawing attention for their prowess.

"Things have really changed the past couple years," said Jary Heinemann, a booster and one of the association's coaches, in March 1979. "It used to be that when other teams saw they were playing a Princeton team they thought they had a win in the bag. Not anymore."

In November 1979, Princeton had launched a varsity boys hockey program at its high school. In July 1980, the hockey boosters told the city council it was planning to build an indoor ice arena.

Davis and the other boosters had figured out the first phase of building an ice arena would cost about $240,000 (about $850,000 in 2025 dollars)ŌĆöan impossible number in the existing economy.

Who had that kind of money to spend on an ice arena?

At the helm of the townŌĆÖs credit union, Davis could feel the local economy swinging into a downturn, even if he hoped his credit union members could pitch in to help finance the arena.

"We are not in the best of times right now. For someone to donate $500, they are not just going to give it right out; they are going to have to think about it,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£I'm sure many will have to take out a loan and pay it back over a period of time, and these loans are available."

By mid-1980, there were two city leaders with big problems only a lot of money could solve. Davis with the hoped-for hockey arena and Anderson with the his beloved but financially beleaguered town airport.

But conveniently, both men were developing a friendship with a certain mysterious millionaire.

In late 1980, Mayor Anderson walked into city hall, accompanied by a Latino man ŌĆö dark hair, maybe a foot shorter than City Administrator Greg Withers.

The mayor had someone he wanted Withers to meet. His name was Casey Ramirez.

He wanted to give the city $42,250 for some of the airport land. Just the kind of investment the airport needed to pay its bills.

Davis might not have known it yet, but Ramirez had something planned for him, tooŌĆöa $500,000 interest-free loan to pay for the construction of an indoor ice arena.

Ramirez seemed to be everyoneŌĆÖs lucky break.

NEXT YEAR - May 22, 1981 ŌĆō Princeton Co-op Credit Union

Four days before he planted palm trees in front of city hall, Ramirez had swept into the nearby credit union.

He made it so he was hard to miss, thought Yvonne Culligan, vice president of the credit union.

Ramirez walked in like he owned the place, she thought. He'd talk to all the tellers and cashiers. He acted like he was everyoneŌĆÖs friend.

ŌĆ£He would enter the bank not like a usual customer,ŌĆØ she later testified in court. ŌĆ£He would be more glamorous, like ŌĆśHi, IŌĆÖm here,ŌĆÖ as if everyone should notice his entrance.ŌĆØ

Ramirez would always be carrying a bag or briefcase. He was always there to see Davis to make a deposit.

While cashiers like Joyce Edmonds usually handled RamirezŌĆÖs deposits, this time Culligan decided to handle it herself.

Ramirez and Davis both joined Culligan in the back room, the teller's office.

She counted out Ramirez's cash: $30,000 in $20 bills. No CTR filed.

That same day, Culligan noticed something else odd.

The credit union would often go get cash from Princeton State Bank ŌĆö for a fee ŌĆö to cover its daily flow of ŌĆ£shared draftŌĆØ checks. But that wasnŌĆÖt the case today.

ŌĆ£When I went into the vault that day, I could see they were trading credit union checks from the cash in the vault,ŌĆØ she said, noticing the same thing Edmonds had the previous year.

It seemed that using RamirezŌĆÖs cash as an off-the-books slush fund was a standing practice.

ŌĆ£I asked Jerry Davis,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£I told him I knew what they were doing.ŌĆØ

She later went to get a portfolio file from Davis' desk drawer where she knew he recorded Ramirez transactions. It was missing.

Davis' shadowy accounting of Ramirez's deposits opened other avenues for financial mismanagement, or worse.

A bank examiner later testified in court that he found Davis had kept shoddy documentation of loans offered to Ramirez.

Sometimes there was just a note. In other instances, there was not even a note.

Nor was there any indication Ramirez had a business or collateral to secure the loans ŌĆö nothing to indicate he could ever repay them.

LATE 1981 - DEA office, Minneapolis

Fisk shared his findings with Boulger and Leonhart, the Ramirez case investigators. The credit union business was a crucial piece of the puzzle.

ŌĆ£Casey wasnŌĆÖt just a drug smuggler, he was also a money launderer,ŌĆØ Leonhart said in a recent interview.

Boulger was shocked when he considered what Davis was doing.

ŌĆ£I mean, he broke every rule there is in banking, for what? A hockey arena?ŌĆØ He said in a recent interview. ŌĆ£I guess in law enforcement, it's a little more black and white or something. But it just seemed odd to me that he did what he did, at the cost he did it, for that. I canŌĆÖt wrap my head around that one.ŌĆØ

The team realized that the failure to file CTRs wasnŌĆÖt just a prosecutable crime, it was a strong piece of leverage against Davis. Perhaps he could be pressured to flip and testify against Ramirez.

Besides Fisk's labors, the investigative team was struggling to get any traction in Princeton.

"Surveillance there was near impossible, simply because half the town was his buddy," Boulger said. "He had unlimited access to the airport, and unlike traditional surveillance, where you see a guy was getting his car, now we can follow him. He'd get a plane, and we had no way to follow him at all. That was very unique and very difficult and very frustrating."

Still, Fisk's records and the women's testimony was added to the growing stack of investigative material the team was collecting. It was a lot of information, a lot of records, everything was compiled by hand.

Leonhart made up big calendars and would log those financial records ŌĆö the timing of deposits. SheŌĆÖd log laboriously collected phone records made to Florida and overseas to other known drug dealers, and purchases of aircraft equipment and fuel by Ramirez and his crew.

With every piece of evidence, a picture was emerging, a paper trail of an ongoing criminal enterprise.

ŌĆ£We started to get the patterns,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£We were just putting all that information together. And then when we started doing interviews, we were filling in the blanks there. And you could see patterns. Everything was important.ŌĆØ

The reaping of profits from drug-running was coming into view ŌĆö planes going from Princeton to Florida, then returning to Princeton, then new cash being deposited in the credit union.

RamirezŌĆÖs scheme, ferrying aircraft to Florida and back, seemed to be a way to avoid detection.

He and his crew would make drug smuggling trips, serving essentially as cocaine transportation contractors between cocaine makers in Colombia and sellers in Florida.

For their troubles, they'd be paid in cash.

They would then lie low between trips by running the planes back to Minnesota, along with bags of cash earned from the smuggling trips, deposited in the unassuming small-town credit union.

Now you see them, now you donŌĆÖt.

OCTOBER 1981 - Princeton

On Oct. 5, 1981, Davis resigned as manager of the Princeton Co-op Credit Union, citing health reasons, although rumors circulated that he had been fired for some reason.

His new full-time job: manager of the still-unfinished Princeton Youth Hockey Arena.

Meanwhile, Ramirez started making waves outside of Princeton.

In mid-October Ramirez told residents around Little Elk Lake, about 8 miles south of Princeton, that he hoped to build a floatplane base there, with docking facilities, cottages and a restaurant.

But he ran into a public-opinion buzz-saw when 80 people showed up for a meeting of the Little Elk Lake Association. Many didnŌĆÖt like his plan. They worried about noise and pollution from his floatplanes, as well as dark rumors some had heard about him.

Ramirez struck back.

"Let me clarify some rumors. I am not in white slavery. I'm not in the Mafia. I do not transport drugs up here,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£I don't even know that I have drugs except the ones I need for the headaches I've been getting from you people."

Still, the Little Elk Lake Association members pressed him for details. Ramirez didnŌĆÖt budge.

"I don't ask you about your personal lives,ŌĆØ he said.

Then he folded. He told them he was scrapping the floatplane base plans.

While Ramirez's largesse and plans continued to make local headlines, a big spotlight was turning toward the man who seemed intent on becoming Princeton's patron saint.

A few months after the floatplane base kerfuffle, an ace investigative reporter at WCCO-TV in Minneapolis named Don Shelby was wrapping up reporting on a difficult case, and looking for his next expos├®.

He remembered: There was that one possible story his colleagues Bob Manary and Dave Nimmer had mentioned, something about a mysterious rich guy making a big name for himself in a small town.

Someone named Casey Ramirez.

<<< Read Part 2

Read Part 3 >>>

Follow the series

Notes: This article is based on interviews for this series with Boulger, Fisk, Leonhart, Manary, Nimmer, Shelby and Withers, as well as Ramirez trial transcripts housed in the National Archives in Chicago, microfilmed copies of Princeton newspapers housed in the collections of the in St. Paul, Princeton Union-Eagle photos, clippings and other items archived by the in Princeton, IRS forms archives, the website and coverage of Jerry DavisŌĆÖ 1983 trial by various Minnesota newspapers archived on Davis declined to be interviewed. Anderson, Jackson, Moeckly and Ramirez never responded to multiple interview requests. Edmonds died in 2005.