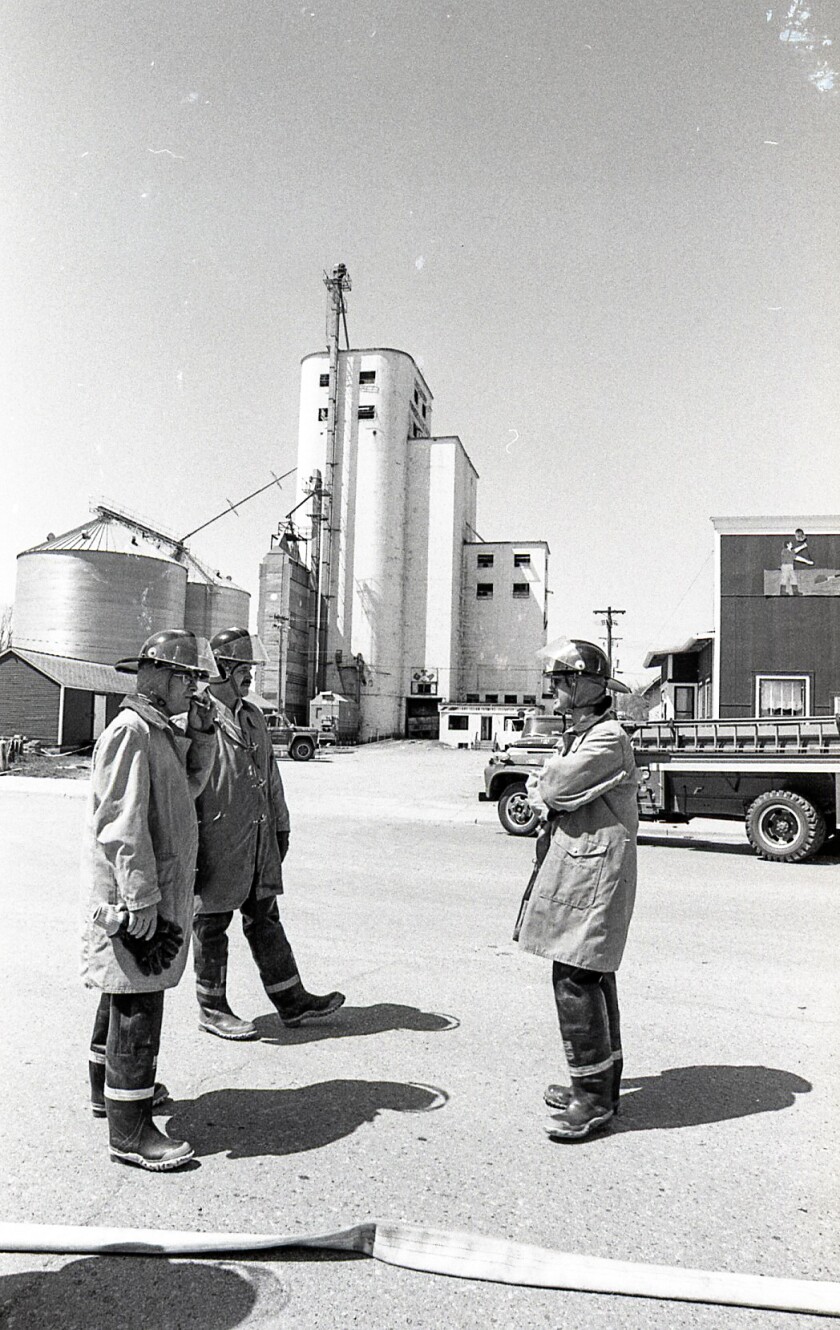

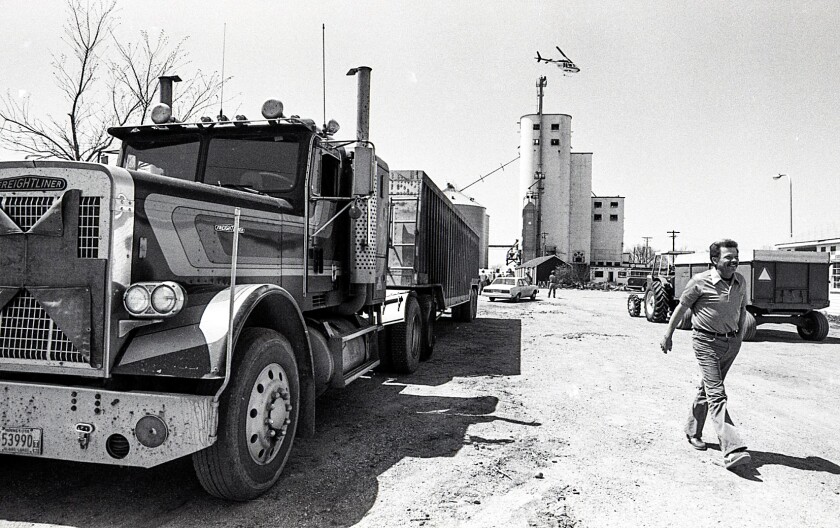

LAKE LILLIAN, Minn. — Forty years after an explosion shot David Garberich out through the double doors of the Lake Lillian Farmers Cooperative Elevator like a cannonball, severely burned and with months of excruciatingly painful recovery ahead of him, he and his wife, Tammy, have one persistent question.

How do you say thank you to all those who came to their aid in the aftermath?

ADVERTISEMENT

“Make sure that people know how thankful we are,” Tammy Garberich said as she and her husband shared their memories of that fateful day and what followed.

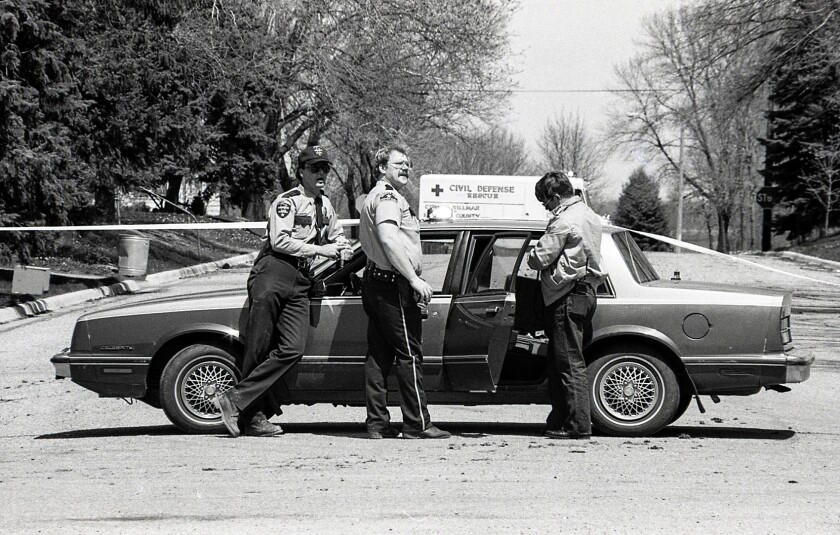

The May 11, 1984, explosion on a Friday morning killed two men and injured four others. Lawrence Fuchs, 63, of Lake Lillian, died of his injuries 11 days after the explosion. Steve Nelson, 35, of Blomkest, died July 31, 1984, of his. The two men and Garberich were the most severely burned.

Brian Wittman, 41 at the time, was the assistant manager of the elevator and among three others injured.

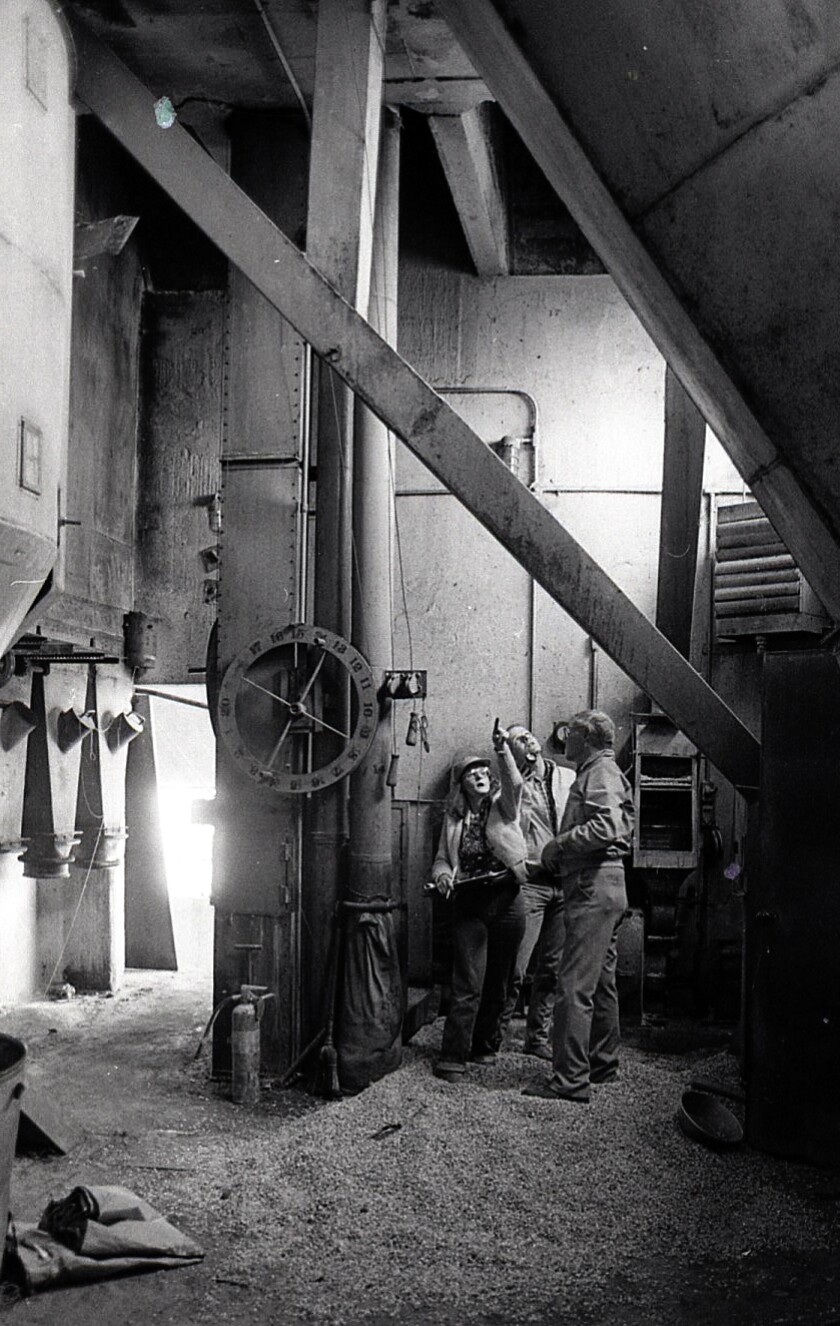

“I heard something out in the mill room,” Wittman said, describing how he and another man, Marvin French, 45 at the time, were in the office when the floor started shaking.

As they opened the door, an explosion ripped through the concrete structure, followed by another and likely another. Wittman said the third knocked him to the floor. He walked out, burns to 15% of his body. Gayle Wright, 31 at the time, was the third injured.

Wittman suffered burns to all of his exposed flesh, especially his face.

“(It) felt like you had shrink wrap on your face and it was just tightening up,” he said of the flash of heat that accompanied the explosion.

ADVERTISEMENT

A stunned Garberich found himself under a truck on the elevator’s scale, which had been moved from its hinges by the blast. He put his hands down to crawl out, and that’s when he felt the first of the excruciating pain that would be his for months to follow. Later, at the St. Paul Ramsey Hospital Burn Center, his father would tell him that his hands looked like “brats left too long on the grill.”

Virtually all of his body was swollen and burned and looked no different than his hands. Fifty-eight percent of his body had second- and third-degree burns. The synthetic clothing he wore was flash-burned and melted; he couldn’t tell if it was clothing or charred skin that hung from him.

Garberich was 8 or 10 feet from ground zero when the explosion occurred. Fuchs was at ground zero.

The two were working in the grinding and mixing room when it’s believed a spark, caused by a small rock or piece of concrete or metal in the grain being ground, ignited grain dust in the air.

“First, there was a small flame. We looked at each other like 'that didn’t look so good,’ ” Garberich said.

“I turned, kind of turned my body to look at him, and the thing I remember is Lawrence standing over the grinder and his hat was about a foot or so above his head. Then I don’t know. It was over with.”

At the time, Garberich was only about seven weeks into his job at the elevator. By an uncanny circumstance, he had read a Reader’s Digest story about medical care for burns just one week earlier. The information it offered probably saved his life twice that day.

ADVERTISEMENT

He knew not to inhale and allow the blast heat to sear his lungs.

Later, as he lay on a grassy area he had crawled to outside of the elevator, a well-intentioned man ran out of the creamery building with a bucket of ice-cold water to douse him.

“No, don’t do that!” he shouted. He knew the shock would have killed him.

Wittman said his wife, Marlene, was an ambulance squad member in Lake Lillian and among the first on the scene. She sat him in the passenger seat, and two other burn victims were placed in the back of the ambulance for a speedy ride to Rice Hospital in Willmar.

All of the victims were initially treated at Rice in Willmar. Garberich, Fuchs and Nelson were transported to the St. Paul burn center. Tammy Garberich had been shopping at Cash Wise in Willmar at the time of the explosion. She was surprised when her sister arrived at the store and told her to go to the hospital.

Doctors in St. Paul initially told the couple that David would likely require a two- or three-month stay there. He managed to cut his recovery time in the burn center to 32 days. The couple learned while he was a patient there that Tammy was expecting their second child.

“OK, I’ve got to get well,” he said he decided.

ADVERTISEMENT

His days there were pain-filled. They started with daily immersions in a solution to kill infections. Nurses used hard-bristled brushes to scrub deep at dead skin. Garberich said at one point he asked to go first each day. Waiting for his turn while hearing the painful anguish of other burn victims going through the procedure was too much.

From the start, both David and Tammy were convinced he would make it. Maybe they were just “young and dumb,” Tammy Garberich said, but she said keeping a positive mental attitude about his recovery was critical.

“Both of us refused to believe life would be any different,” she said.

The outpouring of support from family, friends and others in Lake Lillian and neighboring communities that followed the explosion was unbelievable and made a big difference, they said.

“These rural communities really stand behind you. You can just feel it,” Tammy Garberich said.

On the day she brought her husband home to Lake Lillian, a crowd was at their place cleaning up after a thunderstorm had damaged trees. She recalls her husband going inside.

“He sat down and cried. He was afraid he’d never see home again,” she said.

ADVERTISEMENT

The concrete elevator building still stands today, though it currently is not used. Its upper floors included large windows, by design. They served as a relief valve for the pressure from the blasts, preventing the structure from collapsing in on itself and on those in it, according to Wittman and Garberich.

Wittman returned to work after the elevator was reopened and its interior machinery replaced. The cooperative installed a system to vacuum dust as grain trucks unload.

Garberich said he was told that a variety of factors — from the humidity to the amount of dust suspended in the air — must all be within certain parameters to trigger such an explosion.

According to published reports at the time, federal hearings had been scheduled in Minneapolis prior to the Lake Lillian explosion to consider regulations on grain dust in workplaces. At least 15 others would die in grain dust explosions in the country after the Lake Lillian explosion before the Occupational Safety and Health Administration proposed its final recommended grain dust limit on Dec. 30, 1987, according to the West Central Tribune’s newspaper archives.

The deaths of Fuchs and Nelson remain the most painful of the memories of the tragedy for the survivors. Both Wittman and Garberich spoke of how they respected their co-workers.

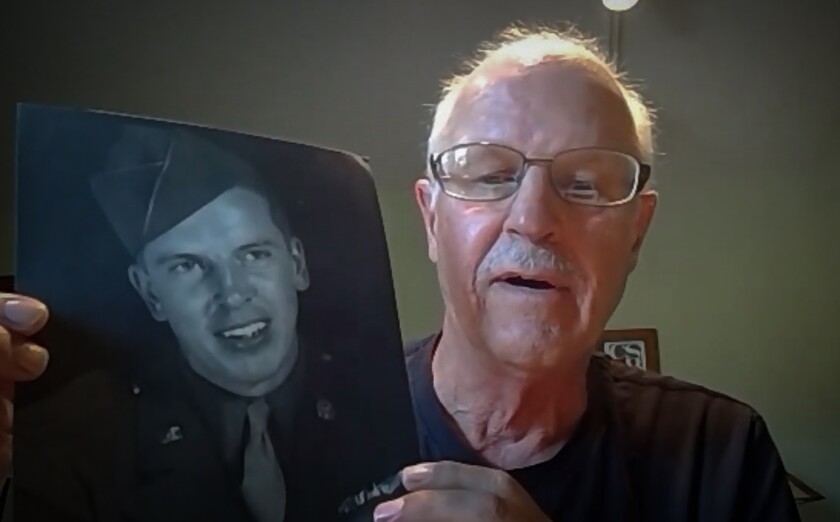

Fuchs was a World War II veteran who had spent time in a German POW camp and returned home with a Purple Heart. He was looking forward to retirement, both men recalled.

Nelson was a Vietnam War veteran, who loved technology and was a member of the Willmar Area Emergency Radio Club. His parents were looking for him to take over the family’s farm, said Garberich. A scholarship is awarded each year at Ridgewater College in Nelson's memory.

ADVERTISEMENT

Garberich endured long months of physical therapy in his recovery but has managed well. Few scars are visible from the burns and many skin grafts. He returned to work as an over-the-road trucker before taking his current role as a driver for the Prinsburg Farmers Cooperative Elevator.

He maintains the same positive attitude that saw him through it all 40 years ago, along with a sense of humor. When asked about the explosion, he likes to tell people: “Yeah, I worked over there in Lake Lillian, but I got fired.”

He donated $1,000 toward a memorial installed in Lake Lillian as part of last year’s centennial celebration to be sure that people do not forget those who lost their lives in the explosion.