HALLOCK, Minn. – It was an idyllic summer day, July 29, 1998. Temperatures hovered around 78 degrees, with a slight breeze weaving throughout the Northern Minnesota prairie.

Sixteen-year-old Julie Holmquist donned her rollerblades and did what she did most summer days: She went for a ride along rural Kittson County Road 1.

ADVERTISEMENT

This time, she never returned.

In the midst of community wide search efforts, a hunter discovered her body three weeks later in a gravel pit roughly 15 miles from her home. Her rollerblades remained intact.

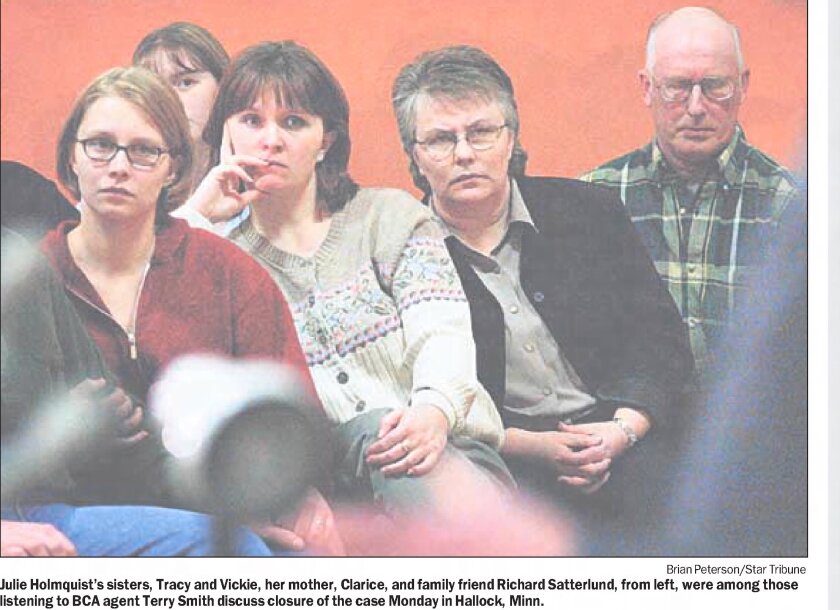

Holmquist’s death devastated the small community of roughly 880 residents. Their collective sense of safety was stolen – and, for more than four years, they waited for the answer to the ultimate question.

The answer came in January 2003, when investigators with the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension held a press conference and named 38-year-old Curtiss Dale Cedergren as the killer.

Cedergren had committed suicide on Aug. 9, 2002, as then-Kittson County Chief Deputy Craig Spilde knocked on his front door to question him about Holmquist’s death. When he asked to speak to Cedergren, he heard a gunshot ring out from the backyard, according to an Associated Press article from the time.

Cedergren had walked outside and shot himself in the head.

Investigators later discovered a gun in his home matching shell casings found near the site where Holmquist was believed to be abducted. It was the final straw investigators needed to tie Cedergren to Holmquist’s murder.

ADVERTISEMENT

What was the evidence?

BCA investigators were quick to say that the case against Cedergren was largely made up of circumstantial evidence. They looked at his abrupt suicide as a confession.

"We strongly believe that Curtiss Dale Cedergren abducted and killed Julie Holmquist," BCA Agent Terry Smith said at the January 2023 press conference, according to an Associated Press article from that time.

There was more than the suicide, though.

Cedergren was interviewed multiple times by investigators. His vehicle matched the description of multiple reports made by girls in the area who claimed to have been followed in the same area where Holmquist was taken.

"When authorities got the information about the young girls who had been followed, you might say stalked, that made the hair stand up on the back of our necks," Smith said at the press conference.

Cedergren also possessed the same model of gun that matched casings found near Holmquist's abduction site.

“In a search of Cedergren's home after his suicide, under some clothing in a closet, investigators found a disassembled .22-caliber semiautomatic pistol,” Smith said at the 2003 press conference.

ADVERTISEMENT

The shell casings that matched Cedergren’s gun were located near Holmquist’s headphones, identified as the abduction site.

Cedergren’s ex-girlfriend told investigators that he told her he was driving on County Road 1, around the time of the abduction. The two were in an argument over their breakup, which was initiated by his ex-girlfriend.

A friend of Cedergren told investigators shortly after Holmquist’s death that Cedergren had made some alarming comments.

During a drive, the two came across a billboard dedicated to Holmquist’s case. When Cedergren’s friend asked if he thought they’d ever find the guy who did it, Cedergren stated the killer would blow his brains out before ever being caught, according to a

When Holmquist was discovered, her body was in a state of decomposition that didn’t allow for DNA samples to be taken. That means investigators did not have the smoking gun they were looking for.

But they knew enough about what happened to her, based on the way she was discovered.

With her rollerblades still on, it was clear to investigators that her clothing had been removed in a way that insinuated sexual assault.

ADVERTISEMENT

And then, she was presumably left in an unassuming location on the outskirts of town.

Investigators did not believe Cedergren knew Holmquist. Instead, they labeled her murder a crime of opportunity.

A bright light

Holmquist was adored in her hometown of Hallock.

She was well-liked and kind with a contagious laugh, according to those who grew up in the area. Her rollerblading routine was part of her volleyball training, something she took seriously.

Her name is honored among those who live in Hallock, who are left wondering what life would have been like for the young athlete, friend, daughter and student.

Each year, Kittson Central ��������, where Holmquist attended, honors her with a scholarship at its spring banquet.

And each spring, faculty, students and community members are reminded of the young girl who was taken from the tight-knit community through a type of violence they hope to never see again.

ADVERTISEMENT