At 8 o’clock in the morning, June 28, 1921, thousands of farmers and onlookers held their breaths as the great National Tractor Farming Demonstration and Show began.

On one side of the 640-acre contest zone, 37 gas-powered metallic tractors roared to life. A few engines had trouble starting, according to newspaper reports found within the archives of The Forum of Fargo-Moorhead. Outfitted with massive steel wheels and tracks, weighing up to 30,000 pounds each, the machines belched black smoke before lurching forward.

ADVERTISEMENT

On the other side, 12 hay-powered draft horse teams, weighing up to 2,000 pounds each and rigged with the latest steel plows — “the primary implement of civilization” — dug their hooves into the Red River Valley soil, called “gumbo” for its sticky clay-like nature. Reliable, trusted beasts bred for pulling heavy loads, left emissions that would fertilize the earth.

Called a herculean contest on a scale never before seen, a battle between machine and horse — change vs. tradition — ensued as the three-day competition’s goal was for each participant to plow, prepare and seed 10 acres of ground, and then compare costs and quality of the work.

Most onlookers in Fargo, North Dakota, had no idea their lives would soon change forever.

“Few of those seeing powerful tractors and plows turning an acre an hour at the Fargo demonstration will realize that they are witnessing the culmination of centuries of man’s efforts to conquer the soil,” a story in the The Forum reported.

Not everyone was excited about change. Some, of Chicago, secretary and propagandist of the Horse Association of America, refused to participate, saying “the much-heralded contest between horses and tractors at Fargo” was a frame-up.

At the time the Red River Valley was considered the second most important agricultural spot in the nation, with fertile soil, a literal breadbasket for the nation. But the weather was unseasonably hot. Weeds were tall. The soil was tough. The contest wasn’t fair, Dinsmore said.

“Such bunk would make a dead man laugh,” Citizen.

ADVERTISEMENT

Months after the event, Dinsmore scorned the crowd size, saying onlookers didn’t add up to 1,000 people because of his earlier “sweeping expose of the scheme, through letters sent to all county agents in Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana.”

“And those present were on the payrolls of the tractor companies,” Dinsmore added.

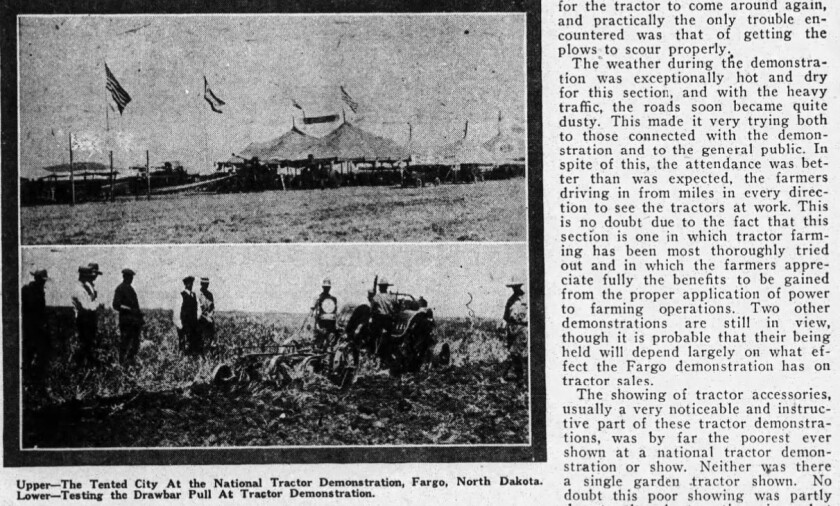

The true numbers, according to The Forum, soared above 10,000 participants. More than 2,500 automobiles were parked all around the sprawling farm, and attendees ambled along the Red Trail, between horticultural and agricultural tents, experimental stations, powerhouse grounds and the actual competitors themselves. People from around the nation booked rooms in Fargo’s 18 hotels, and residents — number 25,914 in 1921 — offered their own homes for rent.

As the contest neared its third day, headlines in the newspaper depicted chaos. A local cigar store was robbed.

The ongoing investigation into in room 30 at the Prescott Hotel was front page news. A few onlookers were arrested for harboring moonshine, a crime since Prohibition began one year earlier, according to The Forum's archives.

Young Ernest Moe was struck by a car at the farming event. He was left lying by the roadside. He survived.

Despite the chaos, the official results became clear that tractors were more efficient than horses. All the horse teams fell behind the machine's speed, and in their efforts to catch up, five horses died.

ADVERTISEMENT

Tallying up the costs of gasoline, kerosene, lubricating oil, pounds of hay and man hours per acre, tractors cost $1.30 per acre and horses ran $2.40 per acre, according to the Hutchinson Gazette.

“Tractor power is cheaper than horsepower,” the in August 1921.

In essence, farmers paid $20 to prepare a 10-acre seedbed with horses, and only $8.97 to do the same work with tractors, according to the Devil’s Lake World. A new tractor in 1921 cost about $650, the equivalent to around $11,400 today. A good draft horse would set a farmer back about $150, or $2,600 today.

“The fight against tractors and trucks may weary some; but it is a fact that the men who have been talked into purchasing such equipment, become short of cash in consequence,” Dinsmore argued.

But farmers could earn their money back, according to contest findings. “Using these figures, the purchase of a tractor, therefore, meant a savings of $318 a year by cutting off the expense of keeping two horses,” the Devil’s Lake World reported.

“So it is not surprising that reports everywhere indicate new interest in tractors and a new idea of power farming as a result of the Fargo farming demonstration,” the Devil’s Lake World reported.

The debate continued on for decades, however, but horses were slowly replaced with machines.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The tractor … has ruined nearly every farmer who has been so unfortunate as to purchase one,” as saying before the results of the competition were publicized in the Lancaster County Citizen.

Critics of the evolution of farming also argued that horses could replicate; while “two tractors don’t easily make three,” The Forum reported.

There was one fundamental difference between horses and tractors that farmers needed to consider, according to the Salt Lake Telegram in 1918.

“The animal power is elastic, while tractor power is absolute,” the that horses can draw on reserve strength, but a tractor had no reserves.

Proponents argued back, saying tractors could run day or night, could plow an acre an hour, allowed farmers to till more acreage and machines weren’t susceptible to disease.

“Horses and mules must be fed and cared for year-round, and farmers needed to set aside about 6 acres of land to harvest feed per animal, per year. With those extra acres now available to grow crops for market, and a tractor that only consumed fuel when it was running, farmers were thrust further into the cash economy,” according to the Smithsonian Institute.

When internal combustion engines — powered by gasoline or kerosene — reached 8,000 horsepower, they became an eco-friendly alternative to the coal-burning steam engines, with about 6,000 horsepower.

ADVERTISEMENT

The new machines would rid the world of smoke-belching chimneys and smog, centralize power plants and save power manufacturers millions of dollars every year, according to the Salt Lake Herald.

“There is no better smoke preventer on the market today than the gas producer. After the plant is in working condition, there is an absolute freedom from smoke,” said Robert Fernald, a professor of mechanical engineering at Washington University in the Salt Lake Herald.

The first gasoline-powered tractor was built in 1892 in Iowa, and manufacturing of the machines didn’t begin on a large scale until 1902. Slow to catch on at first, tractor production increased from 1,000 in 1910 to nearly 5 million in 1970, magazine.

The innovation of the tractor changed the country’s landscape dramatically, allowing some farmers to cultivate more land while millions of others relocated to cities to pursue other interests.

“The U.S. would have been almost 10% poorer in 1955 in the absence of the farm tractor,” the reported.

A titled “What the Bird Man Saw,” featured a reporter who photographed the event from an airplane, publishing a grainy picture in the newspaper in September 1921. The reporter, George E. Fuller, watched like a “bird man” as tractors overtook horses with ease.

“Whiz-zzz! A rush of air — a sensation like shooting upward in a speedy elevator — my plane rose swiftly from the ground at the Fargo farming demonstration,” Fuller reported.

ADVERTISEMENT

He told the pilot to circle the 640 acres, taking pictures as they flew. Tractors were lined up along their respective fields, work already accomplished, while horse outfits slowly furrowed through weeds, Fuller said.

“‘How can the horse compete with the tractor in the face of such evidence?’ I thought. ‘I realized then and there that it is inevitable that horses will be displaced by tractors in field work just as surely as automobiles have displaced them on the road,’” Fuller wrote, adding that he wished every farmer could have seen what he saw that day.