SHAKOPEE, Minn. ŌĆö They didnŌĆÖt hit the road in a convertible and most likely didnŌĆÖt pick up a charming drifter who looked like Brad Pitt. Nonetheless, Edna Larrabee and Beulah Brunelle might be the closest thing Minnesota has ever had to Thelma and Louise.

The two women were the bane of existence for law enforcement authorities in the 1940s.

ADVERTISEMENT

Between 1946 and 1949, the pair broke out of MinnesotaŌĆÖs Shakopee State Reformatory for Women not once, not twice, but five times.

Most of their flights to freedom ended within days, but their fourth attempt was the charm ŌĆö a cross-country adventure during which they evaded law enforcement for eight months by posing as husband and wife.

Edna and Beulah

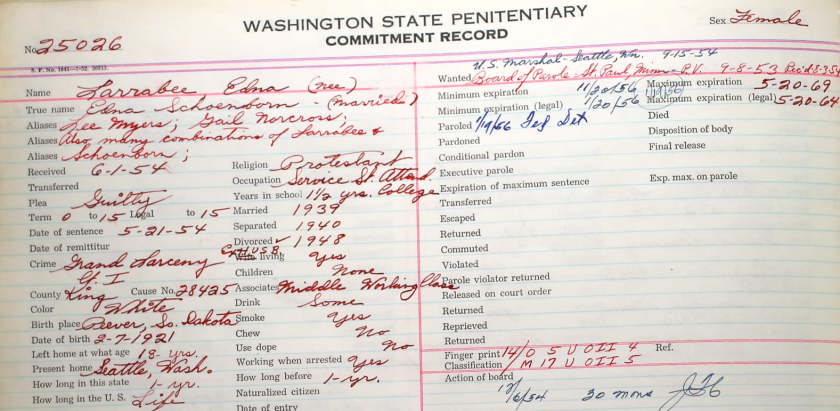

Getting the lowdown on Edna Larrabee isnŌĆÖt easy. Searches on Ancestry.com and Newspapers.com proved challenging. A prison record from Washington State spells out her many aliases, including Edna Larrabee, Edna Schoenborn, Lee Myers and Gail Norcross. However, it seems pretty certain that Edna Larrabee was born in Peever, South Dakota, in 1921.

After two years of high school, she married Elmer Schoenborn in Mahnomen, Minnesota. He was 24, and she was 18.

The marriage was short-lived. Edna had plans for another kind of life.

Following her divorce, her life of crime began. At 19, she and an accomplice stole a car in Perham, Minnesota, and were later arrested in Fergus Falls, Minnesota. Larrabee was also convicted of grand larceny for writing bad checks.

During her first prison stint, from 1940 to 1942, she gained notoriety for her ŌĆ£boyish mannerismsŌĆØ and relationships with other inmates.

ADVERTISEMENT

In a paper titled researcher Lizzie Ehrenhalt and writer Sarah Pawlicki concluded: ŌĆ£Edna could be a thorn in the side of the reformatory staff. One frustrated staff member wrote that Edna was a ŌĆśspoiled bratŌĆÖ decidedly willful who has grown up with the idea that she is ŌĆśdifferentŌĆÖ therefore is answerable to no laws, no authority and will continue in this way, taking every advantage possible as long as she can get by with it.ŌĆØ

Larrabee was also resentful because she believed the parole board paid too much attention to her "tomboy" tendencies and not whether she might be a successful parolee.

When she was sentenced again in 1946, Larrabee, now 25, met Beulah Brunelle, a 20-year-old Ojibwe woman from Belcourt, North Dakota, who was serving time for stealing clothes, shoes and a ring. The two women quickly became partners in crime who refused to stay behind bars.

Breaking free (again and again)

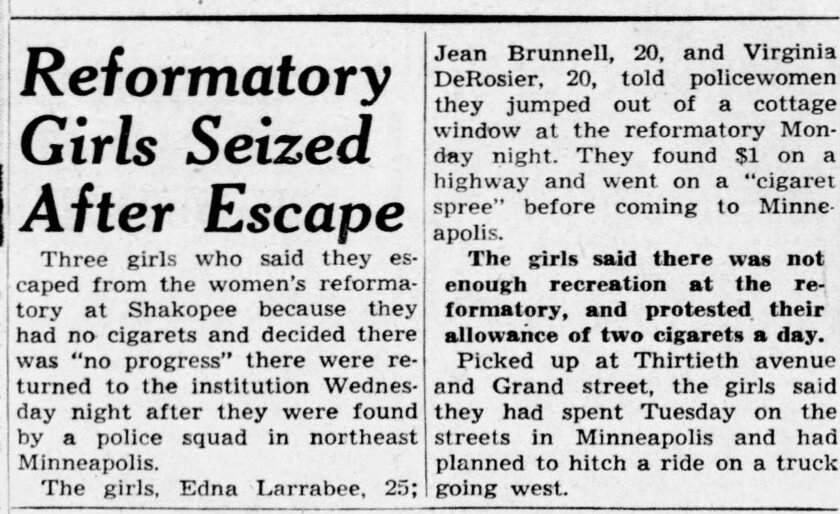

Together, they staged three failed escapes. In their first attempt Nov. 18, 1946, they were joined by a 20-year-old prisoner named Virginia DeRosier. According to newspaper reports, they were captured just two days later in Minneapolis.

They told law enforcement officials they escaped from Shakopee because there wasnŌĆÖt enough recreation at the reformatory and they didnŌĆÖt like that they were only allowed to smoke two cigarettes a day.

In January 1947, Brunelle and Larrabee tried again. Larrabee was eventually caught in Minneapolis and Brunelle in Chicago. They were recommitted to the Shakopee reformatory.

In November 1948, they escaped a third time, slipping out of the reformatoryŌĆÖs religion class and out a restroom window. They were captured again in Des Moines, where they posed as a married couple.

ADVERTISEMENT

After the botched attempt in 1948 left Larrabee in despair, she tried ŌĆö unsuccessfully ŌĆö to take her own life. When that didnŌĆÖt work, she took out her frustration on the prison, flooding her cell and smashing a window. Her rebellion landed her in St. Peter State Hospital for electroshock therapy and psychiatric evaluation.

That hospital stint only strengthened her resolve. Her fourth escape with Brunelle launched them into a fugitive road trip straight out of a Hollywood action film.

On Feb. 2, 1949, Larrabee and Brunelle donned overalls and farm jackets, pried open a nailed-shut basement window, and disappeared into the night. They hit the road under new identities ŌĆö Mr. and Mrs. Patrick Farrell.

On the run

ShakopeeŌĆÖs superintendent, Clara Thune, had a hunch that the pair was headed to California, either the northern or southern part of the state.

Historian Ehrenhalt noted in a Minnesota Historical Society publication, ŌĆ£MNopedia,ŌĆØ that during World War II, Larrabee had worked as an arc welder in San Francisco, and Thune stated that Larrabee was ŌĆ£acquainted with the colony of homo sexuals [sic] in Los AngelesŌĆØ and could show up there as well.

Thune reached out to law enforcement officials from San Diego to San Francisco. But the pair threw authorities off the scent, heading first to Sacramento, where LarrabeeŌĆÖs sister sheltered them. From there, they drifted to Seattle, where they settled for a while, Larrabee running a gas station, Brunelle sewing in a dress shop.

It could have been their happily ever after, but visiting an old friend in Minneapolis spelled their downfall. The friend tipped off police, who traced their black 1936 Plymouth coupe ŌĆö hubcap missing ŌĆö to Sioux City, Iowa. On Oct. 3, 1949, their road trip ended abruptly as officers swooped in, sending them back to Shakopee.

ADVERTISEMENT

A final bid for freedom

They gave it one last shot later that year, but their fifth escape was short-lived. After being recaptured once more, they finally resigned themselves to finishing their sentences. By 1952, they were both paroled and heading in different directions ŌĆö Larrabee to Washington, Brunelle to Minnesota, where she married a man named George Venne.

But their story didnŌĆÖt entirely end there. In 1953, Brunelle made one final, defiant move ŌĆö leaving her husband behind in St. Paul and driving more than 1,600 miles to Seattle, where she and Larrabee found each other once again.

Records indicate that the couple lived together there and later in Minneapolis.

ItŌĆÖs difficult to tell whether Larrabee and Brunelle stayed together after the 1950s. They couldnŌĆÖt be legally married, and detailed census records after 1950 are not readily available online. (According to the National Archives, 1960 Census records will not be released until 2032.)

However, several newspaper stories throughout the 1960s show Larrabee once again running afoul of the law on charges of writing bad checks. Records indicate Larrabee died in 1995, while Brunelle appears to have survived well into the 21st century.