GRAFTON, N.D. — When a group of Grafton residents excitedly prepared for the party at the Edward and Delphine Hein farm on a winter evening 92 years ago, surely they were focused on an evening of fun games, dancing, and some pleasant company to help break up the tedium of the region's harshest season.

Never could they suspect that a deadly guest would also attend.

ADVERTISEMENT

Or that within nine days of that fateful fête on Jan. 29, 1931, that guest would take the lives of 13 of the 17 partygoers.

The culprit was botulism, caused by Mrs. Hein's own home-canned peas and unwittingly served in a salad to guests at the party.

The poisoning also killed Mr. and Mrs. Hein, along with their three oldest children, aged 20 to 16. The Heins’ three youngest boys, one as young as 4, were in bed by the time the late-night lunch was served. They lived, only to lose both their parents within days.

At the time, health officials declared it the “worst botulism outbreak from a single source in a single community in American medical annals.”

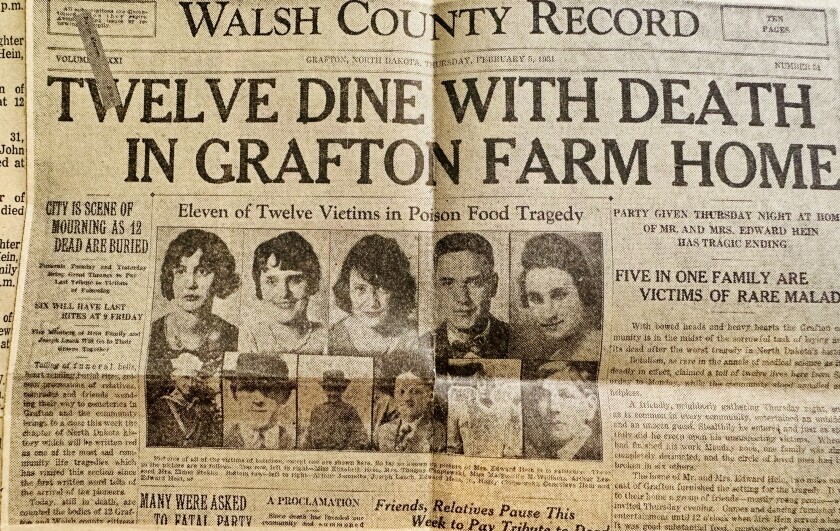

As the hometown weekly, the Walsh County Record ran photos of 12 of the 13 fallen (one of the victims was still alive as of the newspaper’s Feb. 5, 1931, publication) along with an all-caps headline: “TWELVE DINE WITH DEATH IN GRAFTON FARM HOME.”

The lunch in which death lurked

It all started out so innocently — as a show of hospitality from a well-liked and sociable family.

The Walsh County Record painted a picture of a “friendly, neighborly gathering” at the farmstead of the Edward Hein family, which lived two miles northeast of Grafton. Young singles, along with some older folks, were invited so they could mingle.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Heins held the party on a Thursday evening, during which the partygoers played games, visited, and danced until midnight.

Before sending everyone home, Mrs. Hein served a lunch of “good substantial food,” according to the Record. It consisted of buns and wieners, olives, apples, two kinds of cake, and a pea salad, which included her home-canned peas, sliced cheese and mayonnaise dressing placed on a lettuce leaf.

“It was in the salad that death lurked,” the Register reported.

The first one to fall was Arthur Jorandby, 31. A day after the Thursday evening party, Jorandby did his farm chores — although he began complaining of stomach pains. At 11:30 p.m. Friday, he called his brother and asked him to fetch his parents, “for I have awful pains in my stomach.”

A doctor was summoned, but Jorandby slipped into a 15½-hour coma before his death at 3:31 p.m. Saturday.

Although botulism was rare, Grafton physicians diagnosed it almost right away, according to The Forum. An antitoxin or serum had been developed by then, but it was rare, expensive and had to be administered early in order to make any difference.

The second victim was Harry Chapiewski, an eighth-grader from Grafton. The young man attended school as usual the next day and reportedly played well during a basketball game Friday afternoon. He didn’t mention feeling unwell until Friday evening; by 6:10 p.m. Saturday, he was dead.

ADVERTISEMENT

Lifetime friends die 10 seconds apart

Harry’s mom, Mrs. Thomas Chapiwski, was another party guest, as was Mrs. Elmer Stokke, a lifelong friend. The two women spent the day after the party “getting their ironings done” together and planning for a large family dinner.

During the dinner, Mrs. Stokke complained of dizziness, but family members thought little of it, as she frequently suffered from headaches.

By midnight, both women were confined to their beds and a doctor was called. They died “10 seconds apart” at 1:30 a.m. Sunday, according to The Forum.

The first death in the Hein family occurred at 7:30 p.m. Saturday with the passing of 16-year-old Edward Jr., followed by the death of his mother four hours later.

By Sunday night, Edward Sr. and 20-year-old Elizabeth Hein would be gone. Genevieve, 15, died the next morning.

According to Forum reports, the toxic poison “affected all of the victims in practically all the same manner, and with one exception all were conscious until the end and suffered no extreme pain. All complained of dizziness and impaired vision as the first symptoms, followed by failing sight and congested lungs."

ADVERTISEMENT

Most visited with relatives who gathered at their bedsides and forecast their own passing, The Forum reported.

Some conversed right up until their lives ended.

Mrs. Elmer Stokke simply announced to her husband, “I am going to die, Elmer.”

Elmer Stokke survived, as he never ate salad.

The toxin seemed to work at varying rates of speed in different victims. Three days after the party, Margaret McWilliams, a telephone operator, walked into the Grafton Deaconess hospital and died 3½ hours later.

Arthur Lessard, a 24-year-old cousin of Mrs. Stokke, also died that day, just five minutes before McWilliams. Joseph Leach, a 20-year-old nephew of Mrs. Hein, died a day later.

The one who 'almost' survived

Those who survived reported vomiting shortly after the tainted meal, managing to expel the lethal toxin.

ADVERTISEMENT

In fact, Winfield Ware, a 23-year-old farm laborer, was among those who doctors figured would survive, as he lived days after the others had perished. Ware told officials he ate little of the salad and got sick immediately afterward.

Although Ware began experiencing symptoms such as blurry vision and difficulty swallowing days later, doctors attributed the real issue to nervous exhaustion from the trauma of the event.

Even more tragically, a University of Chicago botulism expert had traveled to the area due to the poisoning and had brought botulism serum with him. The medical experts, however, determined Ware’s case wasn’t severe enough to warrant administering the rare and expensive antitoxin.

Ware finally was admitted to the Grafton Deaconess Hospital over a week after the party, where he continued to complain of symptoms. At 7:50 a.m. Sunday — nine days after ingesting the poisoned peas — he sat up in bed and ate a bowl of soup. Five minutes later, he died.

At the time, eight days was considered by medical experts as the maximum time after exposure in which death could occur, according to The Forum.

Ware became the 13th and final victim to mark the unluckiest midnight lunch in the state’s history.

After Ware's death, the three survivors who ate salad were given injections of the serum as a precaution.

ADVERTISEMENT

‘Please, see that mother’s wedding ring is saved’

The people of Grafton were devastated by the swath of death that swept their community.

The funerals stretched over four days, during which time the town’s mayor proclaimed a period of mourning throughout the town and directed all businesses be closed. Services were so full “that only a portion of the throng which sought to pay final tribute was able to gain admittance,” The Forum reported.

The surviving Hein children were taken in by relatives, but their lives were forever changed.

In a 1956 historical article by The Forum, reporter Phil Penas recalled the heartbreaking request made by the oldest surviving son, Dick, who was 14 at the time: “Please, will you see that our mother’s wedding ring is saved so that we have something to remember her by?”

"If only one of our sisters had lived," the boy added, "then we could have continued to operate the farm as our father has in the past."

Penas interviewed an aunt who helped take care of the boys back then. Then 82, Mrs. Charles Maresch recalled how the loss was especially difficult for the youngest, Buddy: “Buddy was not yet 4 at the time,” she recalled. “He was a shy boy, afraid of strangers, and kept asking for his mother.”

Mrs. Maresch remembered how the little boy stayed in bed for three days and refused to eat.

The older two took the tragedy with “grown-up understanding," she said. “They were eager to get out on their own,” she said.

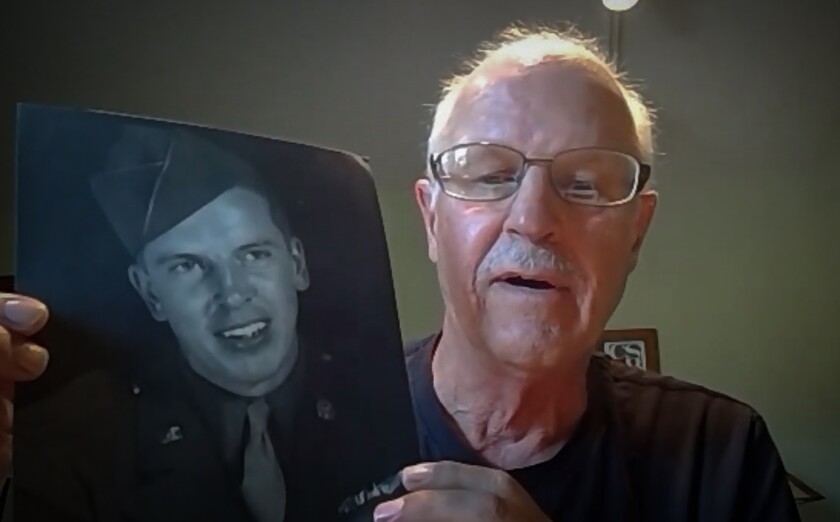

Indeed, Dick would move out of his relatives' home soon after and begin working as a laborer for local farmers. He grew up to walk in his father’s footsteps by operating his own successful dairy operation near Audubon, Minnesota. He

Middle son Wilfred "Bill" Hein was an aircraft factory worker in California in the 1950s. He and his wife had two sons and two daughters. He

Buddy Hein didn’t stray too far from home. After receiving a Purple Heart in World War II, he returned to the area, married, worked in the grain business, and had four daughters. He died in St. Thomas, North Dakota,

Rash of deaths reinforces food safety education

The "poison pea" scare in Grafton resulted in homemakers around the area eyeing their stores of canned goods with a fearful eye.

People were so scared that many dumped out all of their canned goods, even though it was amid the Depression and money was scarce. Mrs. George Harris, a relative of the Heins, recalled a period in which Grafton locals “lived only on toast and tea and oranges.”

Perhaps the one positive development amid all this loss was an

Under the right conditions — such as foods processed without enough salt, sugar or heat — the common Clostridium botulinum bacteria can Today, we know is by processing foods in a pressure canner at 240 degrees for the time recommended in a current USDA research-based publication.

But the trauma wreaked on the families and residents of this northeastern North Dakota town 92 years ago is a reminder of the most lethal and frightening "party guest" in the state's history.

"I believe it is still considered one of the largest botulism poisoning incidents in the U.S.," said Grafton resident Erin Morgan, whose grandfather was married to a Hein.

In fact, her grandfather, grandmother, mom and uncle had all been invited to the fatal party, but did not go.

Morgan said she also knew Marvin “Buddy” Hein, as he was close to Morgan’s mother and used to visit her every summer. Both Buddy and her mother died over a decade ago.

But Morgan will never forget the stories that circulated.

“I remember hearing … how one of the sisters clawed at her throat at the end because her airway was constricted from the poison,” she told The Forum. “I don’t know if that was true or not, but it certainly gave me nightmares.”