BRAINERD, Minnesota — For over 100 years, the Northern Pacific Railway connected the Great Lakes to Puget Sound on the Pacific, powering through the Twin Cities, Brainerd, Fargo, Duluth and more.

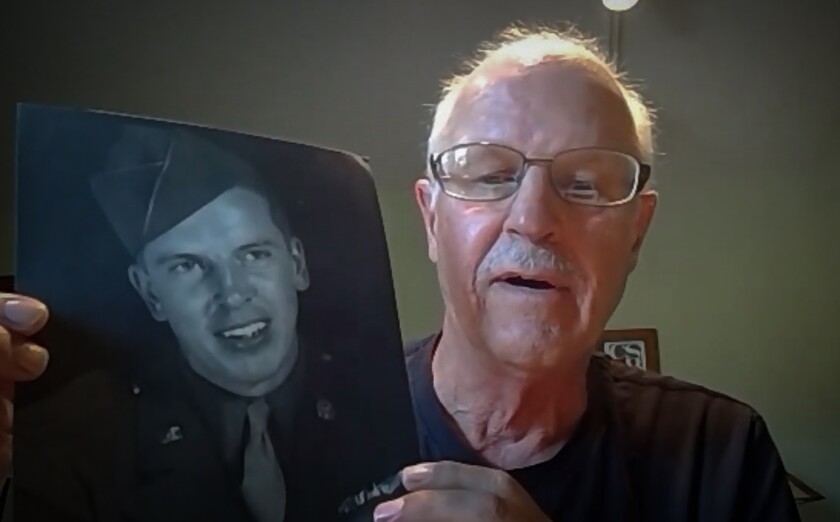

But when Brainerd resident Dan Hegstad went looking for a video on the history of the railroad, he came out empty handed — so he made his own.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Main Street of the Northwest — The Story of the Northern Pacific” aired on Lakeland PBS on June 1 and is now available for free on

Hegstad first suggested a documentary on the Northern Pacific to Lakeland PBS in 2015 when he was the station manager. Seven years passed, and it hadn’t been made. He asked if they would apply for grant funding and let him produce it.

After retiring as station manager, Hegstad found a hobby in photography and videography and transformed it into a freelance business. Affordable editing software and high quality video cameras enabled him to produce a project that would’ve required trucking $100,000 in equipment and a full crew just a few years ago, he said.

“It just wasn’t possible before. It didn’t matter whether you wanted to or not,” Hegstad said. “You would have had to have sponsors and tens of thousands of dollars in funding — just not doable.”

Lakeland PBS received money from Minnesota’s Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund, which has financed over $770 million worth of projects and programs. Under the grant, Hegstad had one year to finish the documentary.

By 2022, he had made considerable progress researching the railroad, but he hit the jackpot with the Northern Pacific Railway Historical Association convention.

Hegstad connected with several experts at the NPRHA’s 2022 convention in Baxter who would go on to participate in his documentary. The NPRHA alternates its annual conventions between the eastern and western ends of the railroad.

ADVERTISEMENT

Sylvan Township has hosted a series of lectures on area history in recent summers, and Hegstad said about 100 people spent one nice night in July learning about ox carts. There he met Jeremy Jackson, a historical researcher who told him about the Northern Pacific.

Enthusiasm of railroad fans

Rochelle, Illinois; Galesburg, Illinois; Fort Madison, Iowa; and Tehachapi, California are probably unknown to most people, but any serious rail fan would recognize them as some of the best train watching locales in the country, Hegstad said.

Besides creating great train-spotting opportunities, railroads have built up the cities they pass through, especially the Northern Pacific.

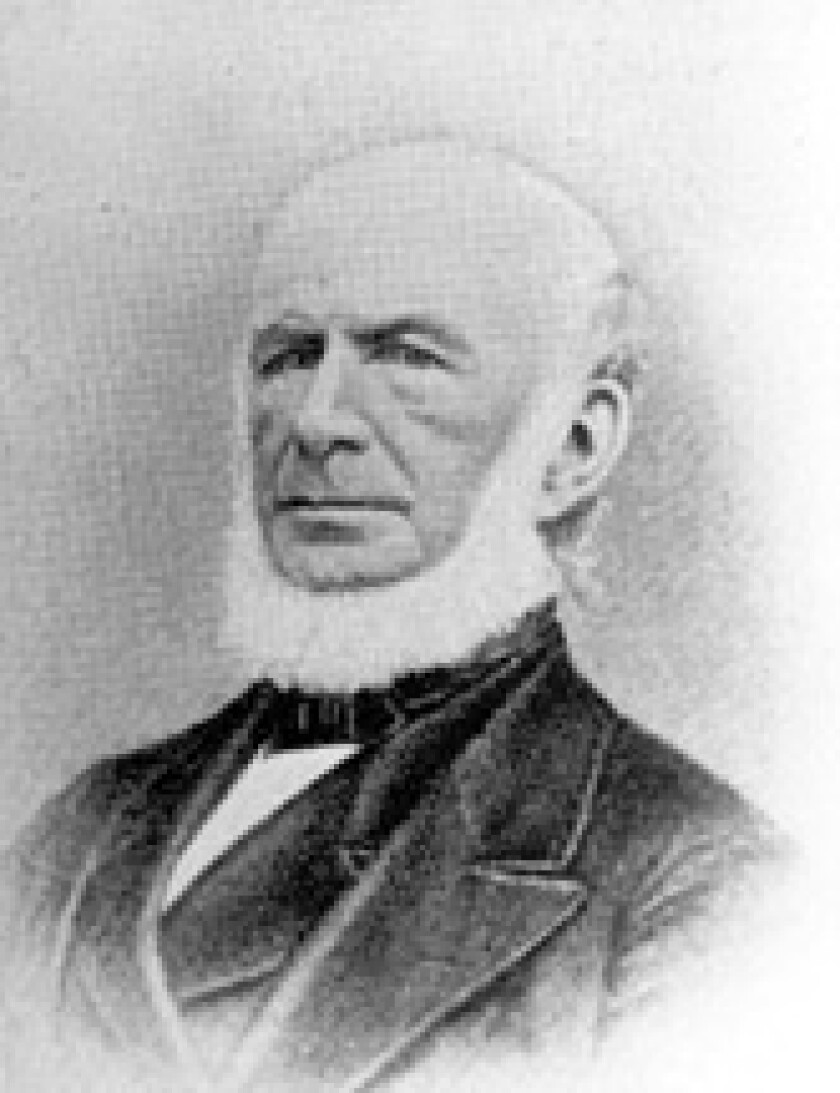

J. Gregory Smith, president of the Northern Pacific Railroad, both selected Brainerd as a point for the railroad to cross the Mississippi River and gave it its name, after United States Senator, and his father-in-law, Lawrence Brainerd.

Other cities — such as Fargo and Moorhead — are also connected to the Northern Pacific Railway in more ways than just being located on the train routes. The cities of Fargo and Moorhead were named for William G. Fargo and William G. Moorhead, who both served as director of the Northern Pacific Railway.

Railroad fans, or self-proclaimed “foamers,” are on the high end of Hegstad’s scale from negative one to four when it comes to trains. Hegstad’s sister is a negative one, he says, and she hates when trains are noisy and block intersections.

Hardly anybody is a zero, or neutral, about trains, Hegstad says. From there, the enthusiasm evolves from passing interest to being able to reference exact pages in train magazines from half a century ago, which he recalled happening when he spoke with Bill Kuebler, one of the featured speakers in the documentary.

ADVERTISEMENT

Hegstad met Kuebler, who shared much of the Northern Pacific’s history in the documentary, at the convention last fall.

“Bill told me he really liked it, and that was a good compliment because he didn’t have to do that, and he was genuine,” Hegstad said. “Getting praise from him mattered a lot.”

Now, Hegstad is at the point where he says he will drive places just to watch the trains.

Being able to identify the make and model of any locomotive, and giving a decent guess as to when it was built, is the marker of the most hardcore fans, according to Hegstad. And if they don’t have the knowledge off hand, they certainly know how to find out.

“It’s just amazing,” Hegstad said.

Hegstad plans to attend the NPRHA convention in Tacoma this year, so he can thank those who participated in the documentary and helped identify mistakes during the editing process.

ADVERTISEMENT

Making the documentary

The 90-minute documentary was originally intended to be an hour, but Hegstad requested more time when he realized he had collected enough information to keep the story long and compact.

“From what I hear, I guess I hit the sweet spot of what’s interesting without going too far into the weeds,” Hegstad said.

The first thing convention-goers told Hegstad when he asked what he should say about the Northern Pacific is that it was like a family. Some spent decades working for the railroad alongside people they’d known for most of that time.

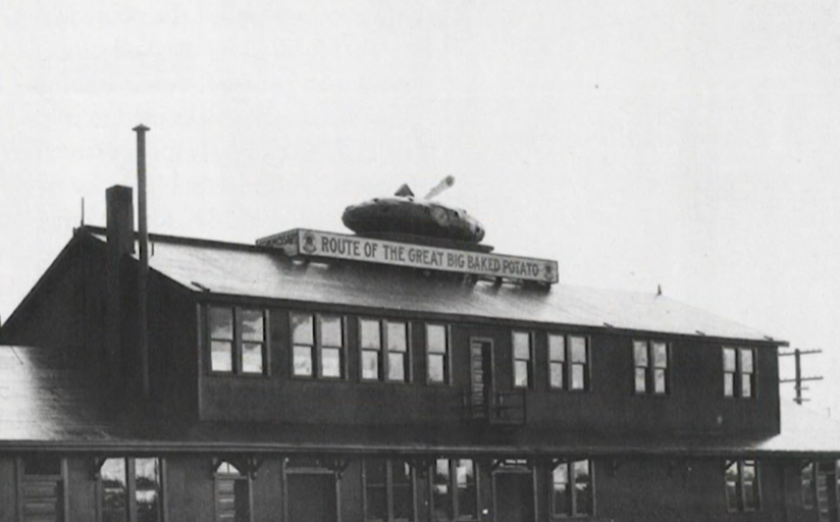

One of the most interesting chapters in the Northern Pacific story is that of the Great Big Baked Potato, Hegstad said. To attract customers, railroad companies wanted to have unique attractions — for the Northern Pacific, that was the baked potato.

Hegstad recruited his friend Rebecca Timmins to sing the sheet music he had uncovered. She brought on Nancy Albertson to play the piano accompaniment.

Wikipedia’s article on the Northern Pacific was another source of information Hegstad used. The photographs and other primary sources featured in the documentary came from individuals, and Hegstad said no one denied him permission.

One question people often raise is the railway’s black and red logo, Hegstad said. The company published a pamphlet on it, and he chose to include the background in the documentary.

ADVERTISEMENT

“By the time I was done, and hit the final save, and sent it off… I was kind of sad to be done,” Hegstad said. “It was very bittersweet.”

Hegstad hoped the film would appeal regardless of anyone’s interest in trains, and he said he’s had people who are not interested in trains tell him they enjoyed watching it.

“Everybody’s interested in history a little bit,” Hegstad said.

In the future, Hegstad hopes to share the story of the “Blueberry War,” , then Crow Wing Village, wherein two mixed European-Ojibwe brothers were accused of murdering a village girl who mysteriously disappeared in 1872. The governor deployed the Minnesota National Guard, for the first time, to offset fears of retaliation from nearby tribes.

But when the National Guard arrived, the troops discovered they were there to trade their blueberry harvests, and thus the story was dubbed the “Blueberry War.” Historian Jeremy Jackson is writing a book on the story, Hegstad said, and after it’s complete, they would like to collaborate on a film.