FARGO — Two Fargo women have spent most of their lives praying for their brother's freedom.

Betty Ann Peltier Solano, 77, and her sister, Sheila Peltier, 59, are anxiously waiting to learn if their older brother, Leonard Peltier, will be granted parole next month after 47 years in federal prison.

ADVERTISEMENT

This could be his last chance at freedom, Peltier Solano said.

“I just feel so sad,” she said. “So much time has passed. He’s been in there so many years. I don’t know how to describe it. I just feel lost. I just hope and pray, hope and pray. That’s all I can do.”

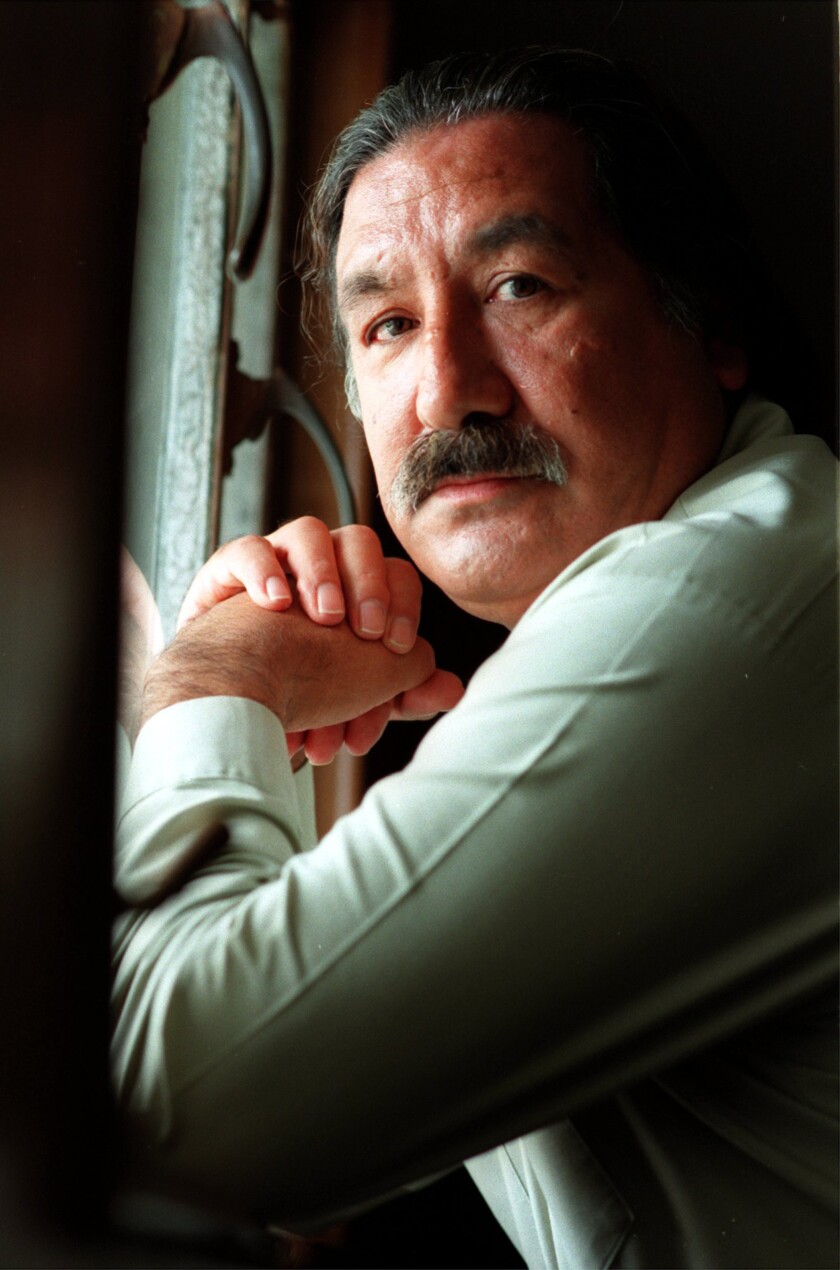

Leonard Peltier, 79, an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, is serving two consecutive terms of life in prison for aiding and abetting in the murders of two FBI agents during a 1975 shootout on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in southwest South Dakota.

His incarceration has garnered global attention with questions about the fairness of the trial and the racial tension of the time rousing the cry of "Free Leonard Peltier."

Tensions running high

In the 1970s, Leonard Peltier was a member of the — a national organization founded in Minneapolis that

His conviction came on the heels of the on the Pine Ridge Reservation. During the occupation, hundreds of activists gathered for a 71-day standoff with the U.S. government — including swarms of FBI agents — demanding the government uphold its treaty obligations to the Lakota people.

Tensions were still running high by 1975. Reports from Pine Ridge during the 1970s depict a war zone; between 1973 and 1975, there were 60 unsolved murders.

ADVERTISEMENT

Violence at Pine Ridge goes back to the 1890s, when following a government ban on the tribe’s religious practices.

For Leonard Peltier's sisters, the systemic inequities that led to their brother’s conviction by an all-white jury in Fargo are still visible today, with Indigenous deaths and disappearances going unsolved and a

'It’s been really painful'

Peltier Solano sat down with The Forum at her south Fargo home on June 17, one week after her brother’s parole hearing.

The walls and shelves were covered in family photos and artwork Leonard Peltier painted in prison.

“It’s been pretty rough knowing he is in there and there ain't nothing you can do,” Peltier Solano said. “Almost his whole life, you know?”

It’s been decades since Peltier Solano and Sheila Peltier saw their brother in person. He was sent to a Florida prison, making it difficult for his family to visit.

The sisters live with the shadow of their brother's incarceration hanging over them.

ADVERTISEMENT

“It’s been really painful. Really, really painful,” Peltier Solano said.

This is Leonard Peltier's first chance at parole since 2009. Given his age, it could be his last.

The parole board must decide whether he will be released by July 11, Sheila Peltier said, and the wait has been nerve-wracking.

Still, all you can do is hope, she said.

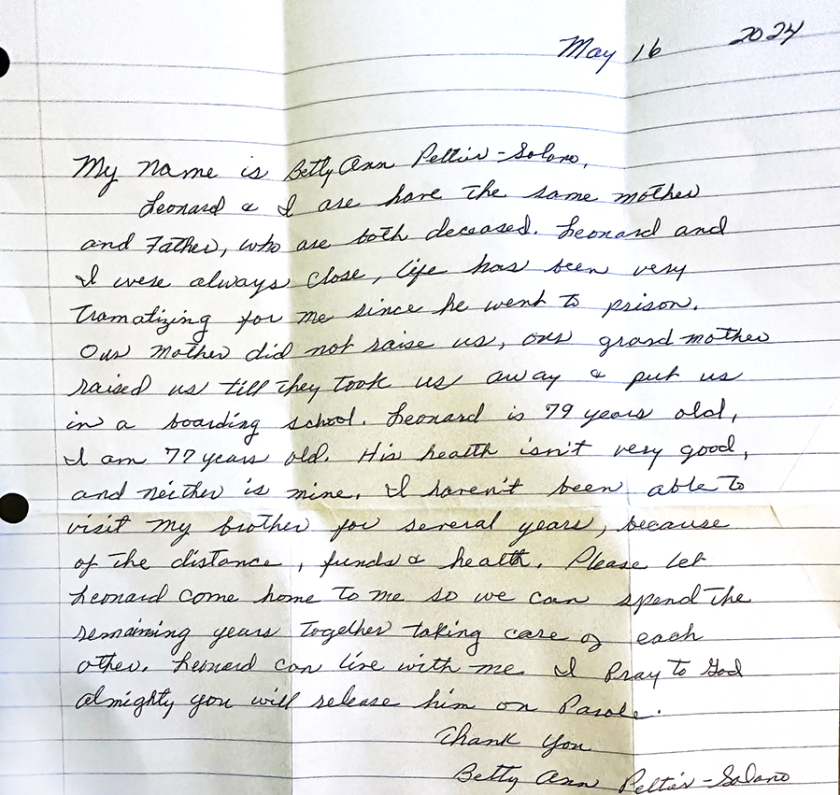

Peltier Solano wasn’t allowed to speak to the parole board on behalf of her brother last Monday. Not being able to go there and speak was “just another letdown,” she said tearfully after a lengthy pause.

She sent a letter instead.

“I hope he gets out. Otherwise, with his health, he’s not going to be alive very many more years,” Peltier Solano said. “I was hoping we could spend our last years together. That would be nice.”

ADVERTISEMENT

'Remorseless killer'

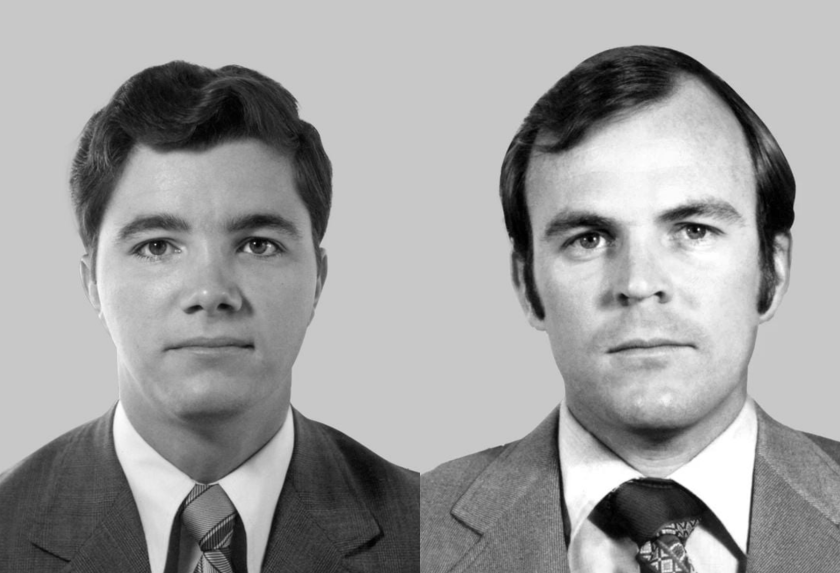

The murders of FBI special agents Ronald Williams and Jack Coler occurred on the warm afternoon of June 26, 1975, when they stopped a vehicle during their search for a man with an outstanding warrant.

Witness testimony later identified Leonard Peltier and two others as occupants of the vehicle, according to the FBI. None of them were the man the agents sought, but the situation turned deadly.

When the shootout ended, three men were dead: Williams, Coler and 23-year-old American Indian Movement member Joseph Bedell Schultz, a citizen of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe. Schultz was not involved in the initial traffic stop, according to the FBI. After the shooting started, nearby people came and shot at Williams and Coler.

After fleeing to Canada and being extradited to the United States, Leonard Peltier was tried in Fargo and found guilty of both murders. Federal prosecutors later changed his charges to aiding and abetting in the two murders.

Some have alleged trial misconduct in Leonard Peltier’s case, including claims witnesses were coerced into testifying against him.

Often referred to as a political prisoner, Leonard Peltier was the only person in the vehicle convicted following the murders.

At 47 years behind bars, he has already served a longer sentence than most people convicted of murder.

ADVERTISEMENT

However, the FBI stands firmly opposed to his release.

“(Leonard) Peltier is a remorseless killer who brutally murdered two of our own before embarking on a violent flight from justice,” FBI Director Christopher Wray wrote in a letter to the parole board. “Throughout the years, Peltier has never accepted responsibility or shown remorse. He is wholly unfit for parole.”

All claims that Leonard Peltier is unjustly incarcerated are “meritless,” Wray wrote.

Coler’s younger sisters stand against Leonard Peltier’s parole, as well, Wray said.

Coler's family members "have never really had a chance for closure,” his sisters said, according to Wray. “We are subjected to hearing and thinking about him (Peltier), reliving that time more often than we should. Parole hearings, Pardon and Clemency requests, books, movies, etc. Nothing has changed regarding this case in the last 47 years.”

Leonard Peltier has remained insistent that he is not guilty, and activists have echoed his cries.

Since his conviction, a long list of people, tribes and organizations have called for Leonard Peltier’s release, including the former prosecutor in the case, members of Congress, Amnesty International USA, Pope Francis, the Dalai Lama, the National Congress of American Indians and dozens of tribal nations — including his own.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 2022, a

The UN working group alleged the FBI targeted Leonard Peltier because of his political activism in promoting Native American rights and said FBI agents harassed him.

They also said the judge presiding in the case previously used anti-Native American stereotypes during jury instructions and that Leonard Peltier’s attempts at parole over the years were quashed, in part, due to anti-Native American bias.

'They made it sound like we were savages'

In Peltier Solano’s living room hangs a photo of herself and Leonard Peltier as children back home on the Turtle Mountain Reservation.

Leonard Peltier is the oldest of 10 children, she said.

Peltier Solano was too young to remember the day that she and Leonard Peltier were taken away from their grandmother and sent to the Wahpeton Indian ��������.

to wipe out Indigenous cultures. Children were taken from their families and communities for years on end and forced to assimilate into European culture.

Many children died at these schools, according to the and others were traumatized.

Not every student had a bad experience, however. Thinking back, Peltier Solano doesn’t remember that time as terrible.

The same can’t be said about Leonard Peltier, who was nine years old when he was brought to Wahpeton.

“Leonard had it rough there,” Peltier Solano said. “They were mean to the boys.”

by on Scribd

The siblings were there for years.

When they left, Peltier Solano was sent to a Fargo orphanage while Leonard Peltier went west to fight for Native rights, she said.

After he was arrested, Peltier Solano attended every one of her brother's court dates.

Sheila Peltier was 12 when her brother went to trial in Fargo, and she remembers how “hostile” the atmosphere was.

The jury was hustled from the courtroom at the end of every day to a bus with blacked-out windows, she said, with people saying, “Indians were going to attack.”

No one there wanted to hurt anyone, Peltier Solano said. Everyone was there to make sure Leonard Peltier got a fair trial. She remembers being astounded by the way the prosecutor was painting him.

“They made it sound like we were savages,” Peltier Solano said, “Like they had to watch out for the Indians.”

'Biggest Indian reservation in the country'

The Peltier family has lost two family members to violent crime.

“American Indian and Alaska Native people are at a disproportionate risk of experiencing violence, murder, or going missing and make up a significant portion of the missing and murdered cases,” according to the

Elmer DeCoteau and Conway Wessels were both killed. Thinking about her nephews brings Sheila Peltier to tears, becoming too choked up to discuss it.

Neither man saw justice, she said.

“They (law enforcement) never found his killer, either,” Peltier Solano said of Wessels. “Probably didn’t even look.”

The system fails to protect Indigenous people, Sheila Peltier said, and steps in with thunderous justice when a white person is killed.

Indigenous people in the United States are “vastly overrepresented” in the prison system, according to the They are imprisoned at four times the rate of white Americans per capita.

“Leonard says the biggest Indian reservation in the country is the U.S. federal penitentiary system,” Dawn Lawson, assistant director of the Leonard Peltier Ad Hoc Committee, told The Forum.

Having been on both sides of the court system — both as the family member of two victims and the sister of a convicted man — Sheila Peltier doesn’t understand how the families of Coler and Williams can be content with her brother's continued incarceration.

“My heart goes out to their families, of course,” Sheila Peltier said. “I’m not saying anything bad about Williams and Coler's family.”

Leonard Peltier's guilt has never been proven, Sheila Peltier said, and if someone was convicted of her nephews’ murders, she wouldn’t feel happy about that without proof they did it.

“The FBI wanted somebody to pay,” Peltier Solano said.

The U.S. has been trying to wipe out Native Americans and their culture since the first settlers came here, Sheila Peltier said. They’ve tried everything from to and now, rampant incarceration.

“Indians never die,” Sheila Peltier said. “They just fade away.”

Leonard Peltier's life now

At 79, Leonard Peltier is navigating multiple health concerns, according to the Leonard Peltier Official Ad Hoc Committee, including diabetes, vision loss, heart problems and lingering effects of COVID-19.

“Leonard – an Indigenous activist, artist, and great-grandfather- will be 80 years old in September,” said a June 7 statement from the “He has multiple debilitating and painful conditions, some life-threatening, that are not being treated in federal prison. Leonard Peltier is one of the longest held political prisoners in the world, in his struggle to defend his people against genocide.”

If he isn’t granted parole this month, they will appeal and keep fighting, Lawson said.

While awaiting his parole decision, Leonard Peltier’s legal team is working to get him transferred to a medical facility in Rochester, Minnesota, and

“I just hope he gets out,” Peltier Solano said. “I hope people just keep on doing what they are doing. Praying for him and just being there for him so he knows he is not alone.”

Through it all, his sisters said, Leonard Peltier has kept his sense of humor. Spending all those years locked up alone takes a powerful mind, Sheila Peltier said.

“That’s the Indian sense of humor,” she said. “If you don’t have your sense of humor, what do you have?”

A family's hope for the future

Leonard Peltier hopes to return to Turtle Mountain Reservation and spend his remaining years with his family.

“He’s mentioned that when he gets out — he doesn’t say 'if,' he says 'when' — he wants to go back home and spend a few days in the woods and in the wilderness,” Sheila Peltier said.

Both sisters hope to visit him frequently at their shared birthplace to make up for years apart and get to know their brother again.

Looking back, Peltier Solano’s favorite memories with her brother were driving around the reservation in his convertible with the top down and the wind whipping through their hair.