ST. PAUL — Several skeptical justices on Monday appeared to suggest that a Chisholm, Minnesota, man may have been denied the opportunity to present a full defense to charges that he raped and murdered a woman in 1986.

The Minnesota Supreme Court also posed numerous questions to attorneys about the use of a decades-old DNA specimen that helped identify Michael Allan Carbo Jr. as a suspect in the murder of Nancy Daugherty.

ADVERTISEMENT

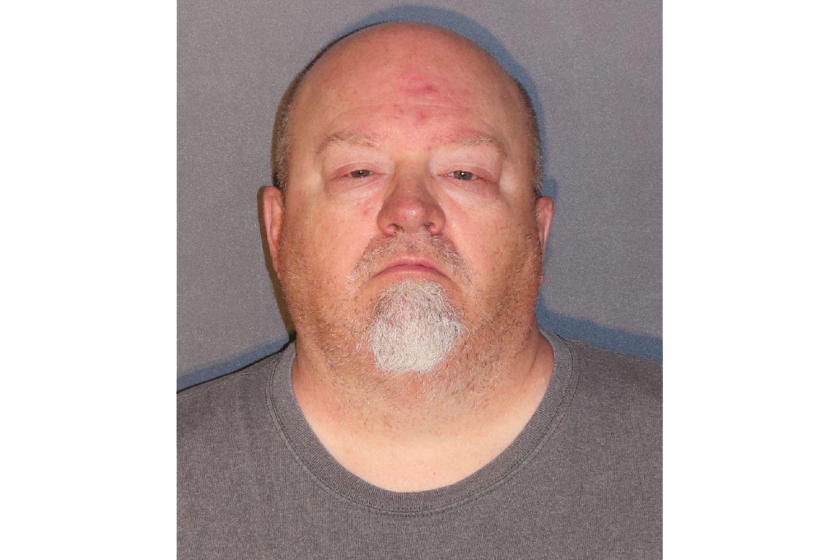

Carbo, 55, is serving a life sentence with the possibility of parole after 17 years after a Hibbing jury last year found him to be responsible for killing the 38-year-old mother of two when he was 18.

In appealing, Carbo is challenging two key decisions from Judge Robert Friday. One upheld the constitutionality of a genetic investigation that ultimately led to his arrest, while the other prohibited defense attorneys from introducing evidence of an alternative perpetrator.

Was 'wrong standard' applied to other man?

DNA from several sources at the crime scene, including semen, were conclusively shown to be a match with Carbo. His DNA was also found under Daugherty's fingernails, and authorities said there were signs of a struggle both inside and outside the house.

The defense didn't deny that Carbo engaged in sexual intercourse with Daugherty but asserted he was not the man who killed her. Attorneys repeatedly sought to present evidence pointing to Daugherty's friend and onetime lover, Brian Evenson, who was otherwise the last known person to see her alive.

The defense said Evenson's hair was found in Daugherty's bedroom, where she was killed, and a neighbor had seen a vehicle matching his in the driveway around the time of the murder. He reportedly sent her numerous letters expressing jealousy after they broke up, including one in which he wrote: "There are times that I think about you that I get so mad I could wring your neck."

Evenson, according to the defense, also acknowledged having a temper and stated in a 1998 interview with law enforcement: "I've often wondered, 'Jeez, did I wake up in the middle of the night, drive over here and kill her, go back to bed and not know it?'"

Judge Friday would not allow the evidence at trial, calling it "mere speculation and bare suspicion," and again stood by the ruling at sentencing when he rejected a defense request for a new trial.

ADVERTISEMENT

"He was using the wrong standard," Justice Paul Thissen said Monday. "He was saying the defendant has to prove it was his vehicle, not that there's some suspicion that it was his vehicle. ... You don't have to prove that it was, in fact, the case. You have to just prove that there's an inference that can be drawn from certain facts that he could be one of the suspects."

Justice Gordon Moore suggested there was "tangible evidence located at the crime scene," raising the issue "beyond just motive of unrequited love."

"If this isn't enough, I think there's a question about whether or not anybody gets to an alternative perpetrator defense," Justice Barry Anderson added.

Assistant Minnesota Attorney General Peter Magnuson defended the ruling, saying the issue was "exhaustively addressed" by Friday. He said another judge might have ruled another way, but the decision could only be overturned if the district court clearly abused its discretion in some way.

"(Carbo) is asking this court to take one statement in a letter and one statement in his fifth interview, and we're going to strip it of all context," Magnuson said. "We're going to put those words up and say, 'Boy, that sure is incriminating.'

"The district court didn't do that here. The district court found that this wasn't a threat. It's one phrase in one of 11 letters. And let's look at it in real time. Did (Daugherty) perceive this as a threat? No, she regularly went out for dates with him. She regularly went out for dinner. She went out for drinks. She allowed him in (to her house)."

Was DNA search a privacy violation?

The court, meanwhile, seemed to be debating where to draw the line on the DNA issue in a case that was believed to be the first of its kind in Minnesota.

ADVERTISEMENT

Carbo was never a suspect in the cold case until Chisholm police sent a sample to a private company, Parabon Nanolabs, to conduct a genetic investigation. The company compared it against samples maintained in private databases — mainly contributed by users conducting family research — to build a family tree and identify Carbo, who grew up within a mile of Daugherty and continued to reside in the small town.

Investigators then obtained samples from Carbo to confirm that he was a match for the man who left his DNA at the crime scene.

Judge Friday, while expressing a level of concern about the use and regulation of the emerging technology, said he had no basis to throw out the evidence. He ruled Carbo lacked an expectation of privacy on evidence he "abandoned" at the crime scene and his relatives consented to having their DNA added to the databases.

Appellate public defender Adam Lozeau said the process is unlike traditional DNA tests that would simply determine if two samples were contributed by the same person. He said the investigators, through the contractor's efforts, were able to identify Carbo's ancestors dating back hundreds of years, predict his physical characteristics and even create an image of his anticipated appearance.

"I don't think it's reasonable to think well, just because biological material was left somewhere he was voluntarily relinquishing an expectation of privacy and anything that can now or can later be learned about him from scientifically analyzing that DNA," Lozeau said, noting DNA technology was in its infancy and not widely appreciated by the general public in 1986.

Lozeau said the state and federal supreme courts have previously upheld that testing blood is itself considered a "search," requiring a warrant, even if law enforcement already lawfully had the blood in its possession. He acknowledged the DNA issue hasn't apparently been addressed by any court, but the standard applied to blood should logically be extended.

Magnuson, however, argued that the U.S. Supreme Court has made clear that advances in DNA technology should be embraced when they allow for "more precise identification of guilty parties and for exonerating the not guilty."

The state attorney suggested the defense position was illogical, with Carbo voluntarily leaving a biological specimen at the scene but claiming he maintains an interest in the data contained within that specimen. He added that semen should be treated differently than other bodily samples.

"(Carbo) clearly could have avoided leaving this evidence behind," Magnuson said. "This wasn't like the skin cells that you're leaving all the time, or hair drops out all the time. This was a specific, volitional act, and it's not something that's going to commonly be left at the scene."

ADVERTISEMENT

Anderson suggested it wouldn't be a "major step" for police to simply get a search warrant for a sample already in its possession. But he also appeared to question the practicality, as investigators in the Daugherty case never even suspected Carbo before developing the profile.

The Supreme Court, which automatically hears appeals of first-degree murder convictions, took both issues under advisement. There is no definitive timeline for a ruling, but it generally takes at least several months.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Minnesota filed an amicus brief in Carbo's favor on the DNA issue, while the Minnesota Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers supported his appeal on the alternative perpetrator evidence.

Carbo remains at the Minnesota Correctional Facility in Rush City.