ST. PAUL — When notorious bank robber John Dillinger cracked his Lincoln Court Apartments door 303 to pepper the hallway with his Thompson machine gun on March 30, 1934, he did more than release a hail of bullets toward federal agents and a police officer.

He broke a cardinal rule, one that exposed a well-known-but-rarely-discussed conspiracy leading all the way to the top of the St. Paul Police Department.

ADVERTISEMENT

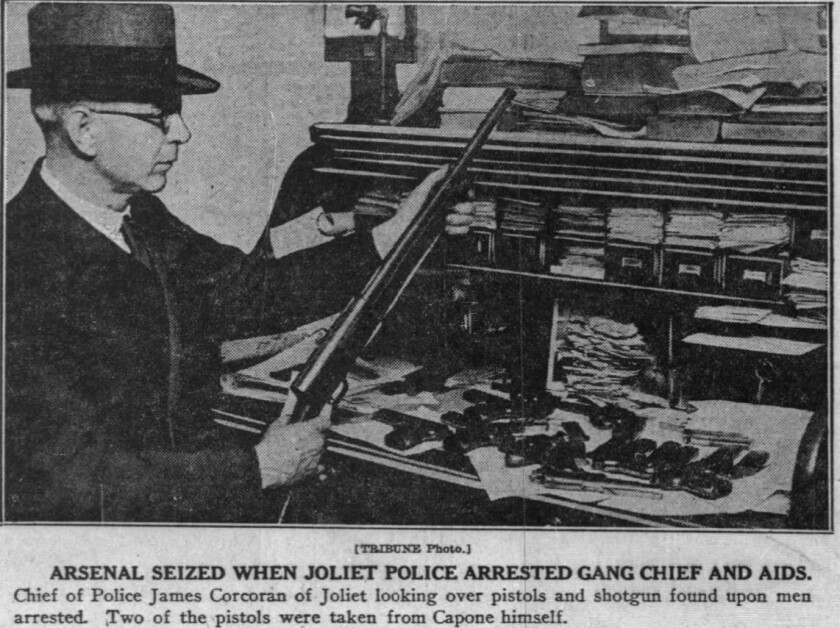

For more than 30 years, the St. Paul Police protected organized crime, offering the city as a safe haven for criminals and gangsters like Dillinger and the beautiful Billie Frechette, Al Capone, Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd, Ma Barker and her boys, George “Babyface” Nelson and Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, so nicknamed for his sinister smile.

In return, gangsters, bootleggers and bank robbers of the Prohibition and Great Depression eras promised to behave in St. Paul. They planned their heists and kidnappings inside their hideouts, and committed the crimes in places elsewhere like in Chicago, or Indiana, or Ohio or Kansas.

Before 1900, St. Paul had a seedy reputation. Originally called “Pig’s Eye” after trader Pierre Parrant, the first settler, the city was renamed in 1841 after a church was built. In the old days, it was a wild western river town rife with murders and robberies, but everything changed when a man named John J. O’Connor became the chief of police in 1900, according to the St. Paul Police Historical Society.

O’Connor, “the Big Fellow," ruled with an iron fist. From his first day in office he consolidated power, created richly upholstered police ambulances, and formed the “Handsome Squad,” sometimes called the by the press, which was made in his image.

He also appointed his charismatic brother, O'Connor, known as the of St. Paul” as the police commissioner.

“He is, as was said, a big man, with a big head; an eye that twinkles in just ordinarily but terrorizes the wrongdoers; a jaw drawn in lines that show the force and doggedness behind the easy-going manner; he is alert and quick in motion, and sharp and decisive in action,” according to the St. Paul Police Historical Society.

A police detective since 1881, O’Connor served until 1912, then he was reappointed to the chief position two years later and served until his final resignation in 1920, dying four years later.

ADVERTISEMENT

St. Paul residents experienced unprecedented peace while O’Connor was police chief, which continued after his death.

O’Connor’s reforms expanded across the first three decades of the 20th century, and his department arguably became the most corrupt police force in the United States, according to “Historical Perspectives on Organized Crime and Terrorism.”

The Layover Agreement

To make the city safe, O’Connor first networked with gangsters of the Upper Midwest, making them deals they couldn't refuse.

All criminals had to do was check in with the police, agree to keep their hands clean while inside St. Paul, and pay a bribe, according to — researcher who spent years researching the city’s relationship with gangsters.

To carry out his plan, O’Connor needed a go between. He found one in William “Reddy” Griffin from within the criminal ranks who worked as the gatekeeper, Society. Criminals were met by Griffin at times by the congested train station, then taken to the Hotel Savoy in downtown St. Paul, according to MinnPost, an independent online newsroom. Griffin’s job was to keep a tally and collect bribes.

“There were bribes like crazy. There was a financial incentive,” Maccabee said.

ADVERTISEMENT

When Griffin died in 1913, “Dapper” Dan Hogan took over his role, according to MinnPost. He died in a car bomb in 1928.

“For the good people of St. Paul, this was not a secret. It was not hidden. Everybody knew that the fix was in between the underworld and the overworld,” Maccabee said.

“What is so fascinating about the O’Connor system — some people call it the Layover Agreement — was that crooks would commit crimes elsewhere and then layover in the city of St. Paul … but one reason was to reduce crime in St. Paul,” Maccabee said.

For some, it was O’Connor’s greatest achievement. O’Connor was hailed as honest, competent and shrewd, the reported. “No one official has done more to make this city where the highest standards of law and order were maintained than Chief O’Connor."

“Never in the history of Saint Paul has human life and the property of citizens been so safe, and the virtue of women so assured.”

“There is a wonderful story, that I think journalist, said: a pickpocket snatched a purse from a woman in St. Paul and the underworld tracked him down, beat him down, and brought the purse back to the police station. They were planning multi-million dollar robberies and kidnappings, they didn’t want a car theft or a purse snatching to get in the way. Ostensibly, you could leave your car unlocked in St. Paul in the 1920s and 1930s, and ostensibly, that was the reason for this deal,” Maccabee said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Speakeasies and more

While a shrewd detective and chief, O’Connor also had a darker, stranger side. He banned public kissing and dancing cheek to cheek. At times he personally beat down criminals who broke the agreement, according to multiple newspaper reports.

His wife until 1922, Annie B. Murphy, reportedly was a madam who out of the popular Bucket of Blood Saloon, a notorious bordello at 222 Eagle Street, according to “Historical Perspectives on Organized Crime and Terrorism,” by of criminal justice at Metropolitan State University.

O’Connor also owned a lucrative horserace gambling business, according to Densley. And he refused to enforce gambling, prostitution and Prohibition laws.

“As far as I can tell, during Prohibition, half of Minnesota was making illegal hooch, liquor, and half of Minnesota was buying and drinking illegal liquor. The cliche is that it was the most unpopular law ever passed,” Maccabee said.

“And there were not dozens, but hundreds of speakeasies in St. Paul during Prohibition. A lot of the bootleggers became the gangsters of the 1920s and 1930s, think of Al Capone. Once Prohibition was repealed, all that money evaporated. Some bootleggers went legit,” Maccabee said.

Like the famous store, Haskells, founded by Benny Haskell, a Prohibition bootlegger turned upstanding citizen of the Twin Cities, Maccabee said.

During the Prohibition, the hooch was stored in soft limestone caves along the Mississippi River, which was historically uses to store cheese, grow mushrooms, and was cool enough to store beer.

ADVERTISEMENT

Gangsters filled the caves with illegal beer, and then for decades after the repeal of Prohibition, the caves were used as nightclubs. The caves — called Wabasha Caves — are still there today.

‘Lesser of two evils’

O’Connor argued that his quid-pro-quo system eliminated major crime and kept St. Paul residents safe, in the Star Tribune on July 5, 1924.

“There are thieves here and there always will be thieves here and in every other city. Some are infinitely more square in keeping their word than some of our supposedly best citizens. If they behaved themselves, I let them go; if they didn’t, I got them. I chose the lesser of two evils,” O’Connor was quoted as saying.

After O’Connor retired, the corruption continued and St. Paul became a “poison spot of crime,” according to many newspapers of the time.

When Prohibition ended in 1933, the city’s criminals looked for new opportunities. No longer able to make money selling illegal liquor, many turned to kidnapping for ransom. In June, the reportedly led by Ma Barker kidnapped president William Hamm Jr.

In January 1934 the gang struck again, this time carrying off Schmidt Brewing Company heir Edward Bremer. The kidnappings alerted the nation and forced the federal government to intervene.

ADVERTISEMENT

While gangsters like Dillinger used the city of St. Paul as a sanctuary, they and police arsenals and successfully broke out of multiple jails from September 1933 until July 1934 outside the city, according to the FBI.

‘Hate-hate relationship’

The Bureau of Investigation, or BOI, was the precursor for the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and was led by J. Edgar Hoover. At the time, they had limited powers, and to make any arrests agents had to be accompanied by local police.

St. Paul’s situation became increasingly frustrating to federal revenue and BOI agents, Maccabee said.

“Hoover and his baby department couldn’t even arrest you without bringing a police officer with them. They were outgunned by the bad guys. The cars that the FBI drove were ludicrous, Dillinger had faster cars. As far as funding, there was very poor financing for what became the FBI. Hoover used the Dillinger gang, the Barker-Karpis gang, the kidnappings, the bank robberies … to make the case that America needed a national police force which it did not have. And he was successful,” Maccabee said.

But before the FBI grew its teeth, the relationship between St. Paul police and the FBI was a “hate-hate relationship,” Maccabee said.

“The St. Paul Police Department would warn the gangsters, saying that the FBI was going to raid your house, you had better leave,” Maccabee said, adding the head of the city’s police kidnap squad, Tom Brown, was the conduit to the gangsters who actually pointed out who could be kidnapped.

Dilllinger’s shootout with police and federal agents and subsequent escape in 1934 signified an end to the gangster era and attracted media attention.

"Why do these dangerous gangsters all head for St. Paul when they want to hide out from authorities or take a rest?" the Pioneer Press editorial board asked in 1934. "Why is this city the happy hunting ground for kidnappers, thugs, thieves and machine gunners?"

Eventually, Dillinger was caught and other gangsters were killed or sent to Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary.

In May 1934, anti-crime crusader and editor of the St. Paul Daily News, Howard Kahn, hired criminologist Wallace Ness Jamie, one of Chicago’s “secret six” who tackled Capone’s criminal empire, to expose the police-underworld corruption, according to the St. Paul Police Historical Society.

He installed bugs, or listening devices, in the police headquarters, to record more than 2,500 incriminating conversations, which led to the agreement’s exposure and disciplinary actions against officers, including Police Chief Michael J. Culligan and at least a dozen others.

Brown, the kidnap squad leader, was exposed in 1936.

“The O'Connor system was over and Saint Paul was no longer a criminal haven. For many decades, it was an unspoken chapter in the city's history. Most of the known gangster hang-outs were either demolished or replaced under new ownership,” the reported.

“What is the lesson in 2024? The O’Connor system was set up more than a century ago. It’s a big lesson, we in America have repeatedly thought we could find common ground with criminals,” Maccabee said.

“The O’Connor system isn’t a precautionary tale; it’s been repeated since then,” Maccabee said.