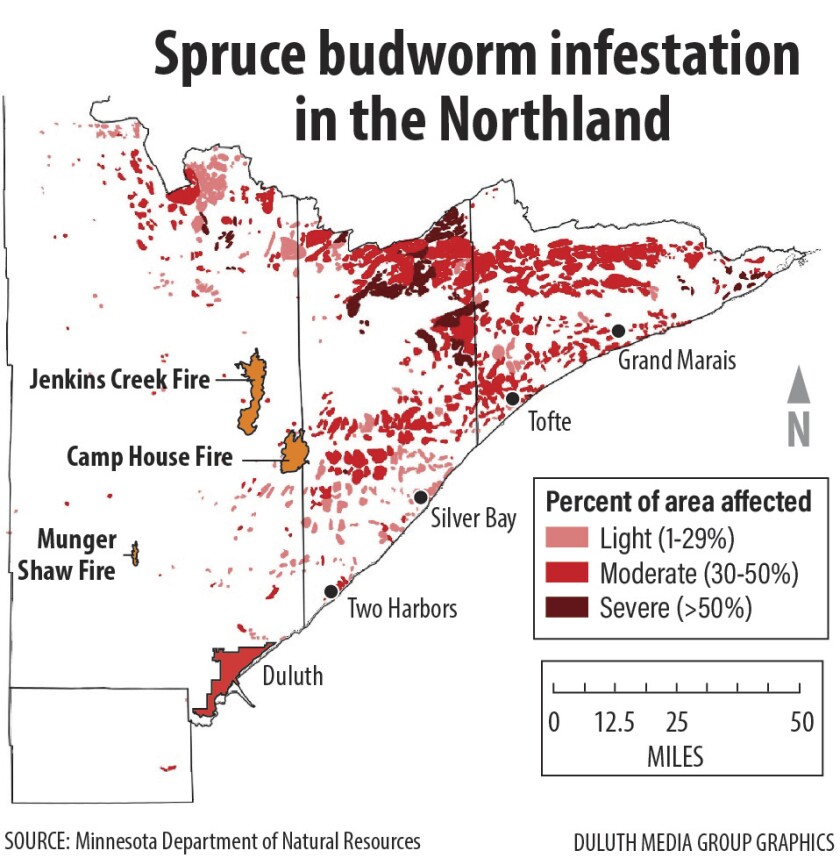

BRIMSON, Minn. — As wildfires spread north of Duluth earlier this month, updates from fire officials on the largest two — Jenkins Creek and Camp House fires — often included a line noting the fire was burning through “a landscape heavily impacted by the spruce budworm.”

A large outbreak of the eastern spruce budworm — a caterpillar native to the region that feeds off balsam fir and white spruce trees — is defoliating the trees and stressing or killing them, which can then help fuel wildfires.

ADVERTISEMENT

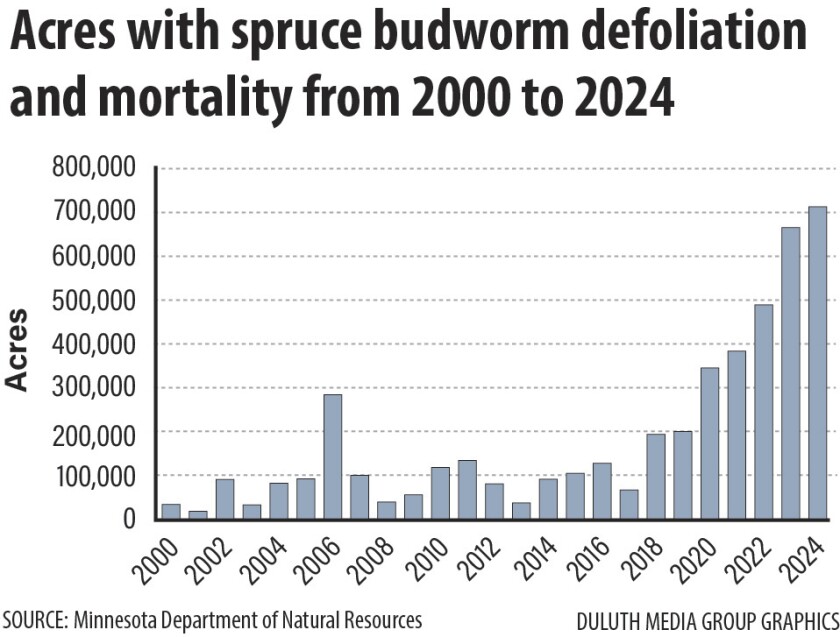

Last year, the budworm affected some 712,000 acres, or 1,100 square miles, of Minnesota forests, almost all in the state's Arrowhead region, the largest area since 1961, according to Eric Otto, a forest health specialist for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources in northeastern Minnesota. If you look at the last four years, it’s affected almost twice that area, according to the DNR’s most recent

“Spruce budworm, currently, is probably one of our biggest forest health issues, especially in regards to the amount of acres it damages each year,” Otto said.

In its caterpillar form, the spruce budworm eats away at the needles of white spruce and balsam fir. (Despite its name, it prefers — and does the most damage to — balsam fir.) Then, as a moth, it lays its eggs on the needles of those trees.

An outbreak in a specific area can last 6 to 10 years, which is about as long as the trees can withstand the budworm’s feeding, according to the DNR.

Otto said that when that food source is gone, the budworms move to an adjacent area, causing an outbreak there. After a 30-to-60-year cycle, they’re back at that first area.

That’s about as long as it takes the balsam fir in the understory to mature, replacing the trees that died in the last outbreak, and for the budworm population to take over again, said Anna Stockstad, an extension educator focused on forest ecosystem health with the University of Minnesota Extension.

Otto said the region last saw an outbreak in the 1990s.

ADVERTISEMENT

Too much balsam fir

Budworm or not, balsam fir is good at spreading fire thanks to its flammable needles, low branches and resinous bark, Otto said.

Those properties act as a ladder fuel, spreading flames from the forest floor to the canopy, where trees otherwise resistant to low-intensity fires can catch fire.

“Even if we didn’t have this spruce budworm outbreak, with the way the forest is composed, we would probably still have these fires,” Otto said, noting the fires were likely human-caused, during exceptionally dry and windy conditions.

But, Otto said, the budworm outbreak probably altered the fire behavior, as dead balsam fir are particularly dry in the spring, some 5 to 8 years after dying from budworm. It isn’t until 10 years or so after the balsam firs die that they start to decompose, increasing their moisture content.

There’s now an overabundance of balsam fir, the budworm’s preferred meal, thanks in part to fire suppression during the 20th and 21st centuries, Stockstad said.

Without regular, low-intensity fires clearing a mature forest’s underbrush, where shade-tolerant balsam firs thrive, the tree species can build up.

ADVERTISEMENT

“So this means we have a lot of dense mature balsam fir on the landscape, which is just like candy for spruce budworm,” Stockstad said. “And so when we have more of the food source for spruce budworm, we’re going to see higher population in spruce budworm itself.”

As the region’s paper mills have shrunk or closed, so too has the market for balsam fir in northeastern Minnesota.

The closure of Duluth’s Verso paper mill in 2020 left UPM Blandin in Grand Rapids as the last mill buying fir in the region, but it’s too far from the budworm outbreak, Otto said.

While some loggers can bring balsam chips to Minnesota Power’s Hibbard Renewable Energy Center in Duluth, which burns wood waste to produce electricity, Chris Dunham, the Nature Conservancy’s associate director of resilience forestry in northeastern Minnesota, said that “doesn’t match the demand in any way, shape or form.”

Still, Stockstad said landowners should consider removing dead balsam, which could be chipped, piled to make wildlife habitats, or, under the right conditions, burned.

Then, landowners can start to consider planting other species of trees.

Striving for a diverse forest

Foresters don’t want to eliminate balsam fir — or even budworms — altogether. Instead, they want more of a variation of tree species, particularly those that can survive low-intensity fires and withstand a warming climate.

ADVERTISEMENT

Dunham and the Nature Conservancy, which partners with government agencies and private landowners, are in the midst of planting 2.5 million trees in northern Minnesota this year. Species include red oak, bur oak, white cedar, yellow birch, tamarack, black spruce and white pine.

“Diversity is the superpower of the forest,” Dunham said. “That’s what enables us to hedge our bets against what is likely coming down the pike. We want to be diverse so that if there’s something that affects another species, we’re not just putting all our eggs in one basket.”

But planting millions of trees is just the first step.

Dunham said crews then must monitor and maintain planting sites for 7 to 10 years to make sure they survive, by pruning for blister rust, clearing brush and guarding against deer.

White pine and white cedar are “absolutely beloved by deer,” Stockstad said, making it hard to establish those species without fencing and other protection. Meanwhile, balsam fir is not a preferred browse species for deer, allowing the tree species to flourish.

“We can’t just cut it and walk away,” Dunham said. “It’s going to take some intervention and investment.”