ROCHESTER — Among those who work in the child care industry in Southeast Minnesota, a general consensus prevails: The system is broken.

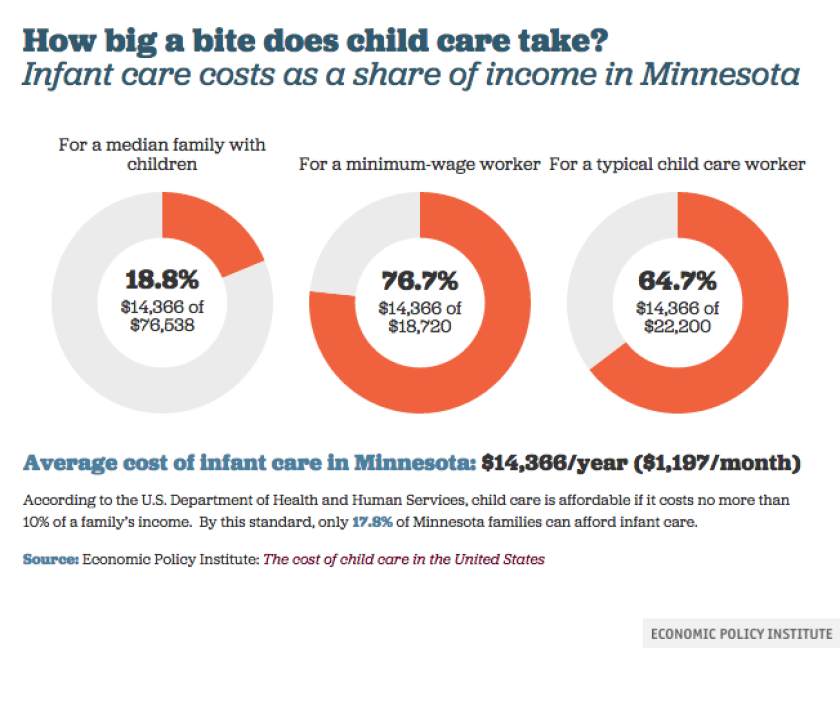

The crisis is reflected in a conundrum. While parents pay top dollar for day care, sometimes amounting to one parent’s salary, day care staff are barely paid subsistence wages.

ADVERTISEMENT

What accounts for the disconnect?

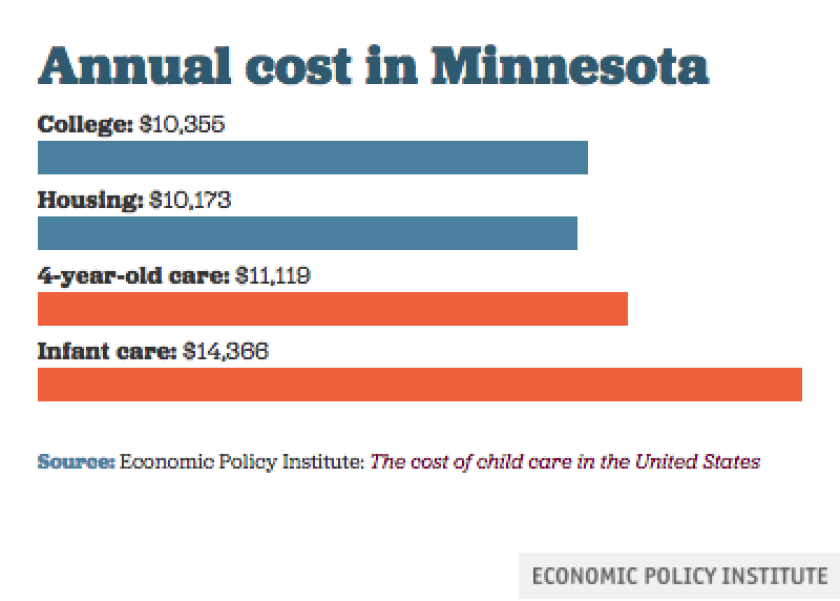

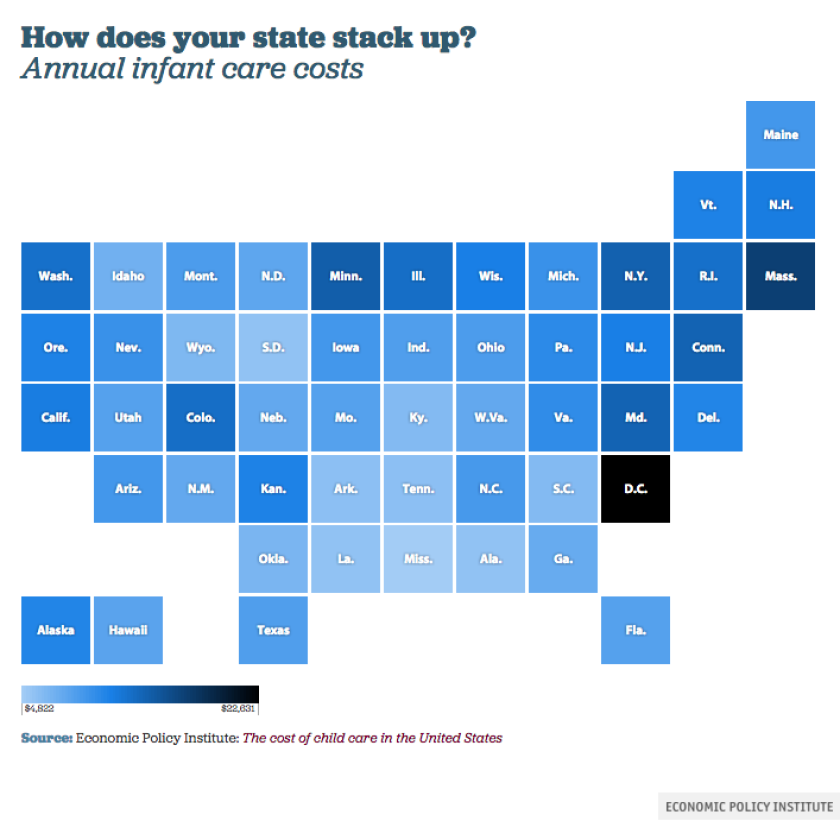

The average annual cost of infant care in Minnesota is nearly $23,000, according to a recent report by the Economic Policy Institute, ranking Minnesota third-highest among U.S. states for the cost of care. The study notes that infant care costs $9,500 more per year than in-state tuition for a four-year public college.

At the same time, providers are struggling with staff shortages, driven by bare-bones pay that makes it hard to attract workers and that keeps providers from operating at full capacity. The average wage for a child care worker in Minnesota is $16 per hour, one of the lowest wages for jobs that require a high school diploma. Retail work offers comparable wages and a lot less stress, providers say.

The result: A desperate day care shortage prevails, deepened by an exodus of family child care providers as the rules and regulations that govern day care have become more onerous and punitive, providers say.

Fifteen years ago, Olmsted County was once home to more than 500 family day care providers, a child care expert said, citing one study. Today, there are fewer than 250.

“We’ve got desperate shortages,” said Jon Losness, retired executive director of Families First of Minnesota, a nonprofit organization focused on early childhood education and child care.

“I tend to believe that markets work generally, but in the child care business, the market doesn’t work,” he said. “Families are paying as much as college tuition to send their child to child care, yet the workers are making wages that qualify them for free and reduced lunches and all sorts of assistance programs.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Providers cite three factors for the escalating costs of child care: the nature of the work itself, the lack of public financing, and burgeoning costs of complying with state rules and regulations.

Operators point out that day care is people-intensive work. The bulk of their budgets is devoted to hiring people. Centers aren’t supported with public financing like schools and colleges. Those costs are thus borne by parents. So centers are thus caught in a tricky balancing act between being mindful of what parents can afford and the growing costs associated with complying with policies and requirements, including paperwork and documentation, imposed by the state.

And unlike a public school classroom of, say, one teacher to 25 students, day care ratios are far smaller: one teacher for every four infants.

And unlike public universities with their summer breaks, day care centers operate year-round, and long hours are the norm. Teachers can spend as many as 10 hours a day with children.

It’s not unusual for centers to find their profit margins hovering from minuscule to nonexistent.

“Some months, we make money, some months we don’t make money,” said Karin Swenson, director of Meadow Park Preschool and Child Care Center, a nonprofit. “We hope at the end of the year that we break even or make a little bit more so that we’re able to give just a couple of percentage points in raises to staff.

“It’s an equation that doesn’t work, because on one side, many of us are not at full capacity because we don’t have staff. And we don’t have staff because the wages are low,” she said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Providers say one of the biggest hurdles they face today is a heavy-handed regulatory environment that, perversely, saps time and energy away from the work of caring for children and adds to their costs. Centers and family providers say the rules have become numerous, burdensome, punitive and, in some instances, contribute little to a child’s safety.

During inspections by licensors overseen by the Department of Health and Human Services, centers can be cited for having too few blocks for children to play with (the rule requires 200 blocks per group). Centers can be written up for leaving unattended mops in the lunchroom or towels on the bathroom floor.

Handy wipes are used extensively at centers, but a center can be dinged if a child can reach for and access the cloth on their own. If it’s handed to them, it’s OK. Licensors deem a wipe lying around a “hazardous object.”

Some rules don’t withstand cost-benefit analysis. Centers, for example, are required to have a dentist on record for an infant.

“In my 13 years of doing this, I’ve never needed it, but I’ve spent a lot of time tracking down a dentist for each infant,” said Teresa Bahr, owner and director of Early Advantage Development Child Care Center.

Complying with the rules and regulations and the way they are interpreted often translates into a growing amount of staff time spent on filling out paperwork, diverting from the care of young children.

The way the violations are described in reports can make the infraction seem worse than it really is, providers say. Chapstick found in a cubby can be described in an inspection report as unauthorized medication put within reach of children.

ADVERTISEMENT

“It’s gotten so far beyond what it was when I started,” Swenson said. “A lot of the laws are the same, but it’s the interpretation that’s been added in there. And it’s just taken off, and it’s gotten to be crazy.”

The citations can do more than reputational harm. Inspection records, including citations, are posted on the Department of Human Services and Parent Aware websites.

And those reports can impact the ability of providers to obtain insurance.

Amy McAndrews, director of First Steps Academy, said she has hired more people with “zero experience with children because I need bodies in these classrooms. Otherwise, I have to terminate care for our clients."

The growing number of rules and requirements puts pressure on these new employees. Instead of engaging with the children, staff are stepping away to check cubby areas “three times a day because who knows how many kiddos put chapstick in their pocket before they come to school,” Andrews said. “And it’s too much pressure for them.”

Oftentimes, providers say, the big picture about whether a day care provider offers an environment for children to grow and thrive gets lost in the attention paid to smaller, less consequential issues.

“When the (licensor) walks in, are the children engaged? Are they happy? Are the adults happy and engaged with the children?” said Jackie Benoit-Petrich, executive director of Civic League Day Nursery in Rochester. “Is there warmth and care and love in the classroom?”

ADVERTISEMENT

Providers say they aren’t arguing for no regulations. Day care centers and family providers should be regulated. The state has an interest in protecting and keeping children safe. But there’s a difference between rules that enhance the well-being of children and those remotely connected to their safety, said Jennifer Parrish, a Rochester family child care provider.

“There’s a difference between saying we need to have outlets plugged and we need to have, you know, we can’t have pet danders in the house. Pet dander. Yes, that was one of the things that they were proposing last year,” she said.

Child care operates at a key intersection in American society. It is critical for the area’s workforce. Parents can’t go to work if they can’t find available day care for their children.

For a long time, the state resisted providing financial assistance to day care. Then the critical role providers play was thrown into sharp relief when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. And money began to pour in to providers in the form of stabilization grants to keep them open.

“All of a sudden, all our doctors and our nurses and essential workers had to go to work during COVID. And, oh my gosh, we need to keep day care centers open. So, all of a sudden, they gave us money,” Benoit-Petrich said.

That support continued in the form of the Great Start Compensation Program, whose direct payments allowed eligible child care providers to bolster staff compensation and benefits.

The dwindling number of day care options means that parents, friends and neighbors are taking care of children while their parents work.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I’ve been doing this for 21 years,” Parrish said, “and I’ve never seen more unlicensed and unregulated care than I see right now, because of the shortage and because of the high cost of center care. There’s just not enough family child care programs out there for most families who don’t qualify for assistance.”

Providers have been working hard for change. One change on the horizon is the manner in which providers are regulated. Come July, the process of evaluating providers will shift from the Department of Health and Human Services to the newly formed Department of Children, Youth and Families.

In time, providers hope that the focus by licensors will narrow to health and safety issues, while programming would become the domain of an accreditation body, such as the National Association for the Education of Young Children. The hope is that these modest steps would set the stage for more substantial reform.

But it would start with how licensors approach their work. “They need to work with us more,” Swenson said.

One goal of such reform, Swenson said, would be to bring greater rationality to the work of making day care accountable and end the piecemeal approach in which operators are answerable to multiple agencies.

The history of such reform efforts has not always been a happy one. Past “modernization” efforts have taken wrong turns, at least in the eyes of providers, resulting not in less regulation but more.

In much the same way that colleges are accredited, such a process would emphasize best practices for providers and open the way for mentoring and coaching instead of just punitive measures.

Off in the horizon is an even bigger dream: that providers would receive public financing like schools and colleges. But it’s hard to imagine that happening any time soon, given the bleak fiscal condition of the state and the country.

“I want this system transformed before I retire,” Swenson said. “We need to see a major transformation before I walk out the door. That’s my mission. I’ve seen over the years how things have changed and gotten so far out of control.”