DULUTH — Ask Minnesotans today to reflect on the legacy of the late Rudy Perpich, and you'll hear a lot of things. Notably, though, there's one word you won't hear.

"We described the 80 counties of Greater Minnesota as 'Outstate,'" remembered Tom Anzelc. "Rudy hated that. He just hated that, and wherever he went, he said, 'Look, we are one state, and we are Greater Minnesota.'"

ADVERTISEMENT

Anzelc was a Hibbing teacher in the late 1960s, he said, when he met Perpich and "immediately was caught up by his charisma, his fun, carefree attitude, and his love for the Iron Range." Anzelc would go on to work in multiple state and local government capacities, including when Perpich served as governor of Minnesota.

Forty years ago this week, on Nov. 2, 1982, Perpich was elected to the state's highest office in a remarkable political comeback. The first and only governor from the Range, Perpich would ultimately become Minnesota's longest-serving governor.

Northland historians agreed the time is ripe to revisit the life and career of a distinctive figure who helped shape the way Minnesotans think and talk about their state.

An Iron Range political dynasty

"It'll be hard for any Iron Ranger to ever get elected governor, on any party's ticket," said Aaron J. Brown, a writer and college instructor who was born, raised and still lives on the Range. Perpich was the only one to date, and "he may hold that title for a good long time."

Born in a three-room house on Carson Lake in 1928, Rudy Perpich was the child of one first-generation Croatian immigrant (his father, Anton) and another who was second-generation (his mother, Mary, who was 17 years old when she gave birth to Rudy). Perpich became part of a local political dynasty that could be regarded as Kennedy-esque, at least in some respects.

"Well, they weren't rich bootleggers," Brown said with a laugh. Anton Perpich was an influential labor organizer, and his four sons grew up talking politics at the dinner table. "Rudy was the most successful of them," continued Brown, but three of the four (Rudy, Tony and George) would serve in the Minnesota Senate.

Rudy Perpich, who practiced dentistry before pursuing elected office, rose to power at a heady time for Minnesota politics.

ADVERTISEMENT

He first became governor in 1976, when Perpich was serving as the state's lieutenant governor. Walter Mondale was elected vice president on a ticket with President-elect Jimmy Carter, clearing Mondale's U.S. Senate seat. Wendell Anderson, then serving as governor, resigned the position in order for Perpich to take that office and appoint Anderson to the Senate.

Perpich ran for a full term in 1978, but lost in what ecstatic Independent-Republicans declared the "Minnesota Massacre." Nearly the entire Democratic-Farmer-Labor ticket lost that fall, "a historic turnaround in the once DFL-dominated state," wrote Perpich biographer Betty Wilson.

While the victorious Gov. Al Quie served a turbulent term rocked by budget crises, Perpich took a Control Data job that sent him to Europe. "We were begging him to come back," remembered Anzelc. "He was reluctant at first, and then he'd come home and he'd meet with us, and he'd talk about the future."

Eventually, Perpich decided to throw his hat back in the ring for a chance to succeed Quie. "That 1982 comeback was historic," Anzelc said. "Out of the box."

'The people's governor'

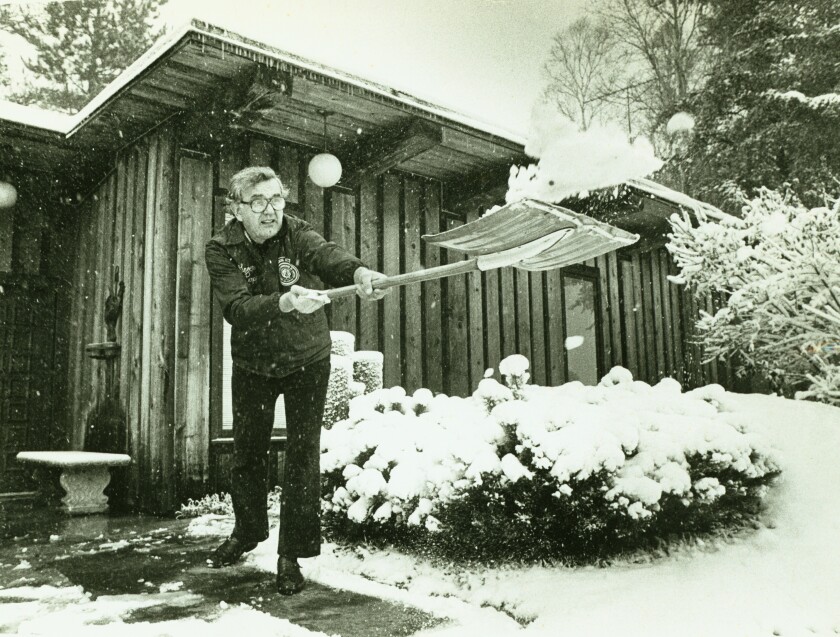

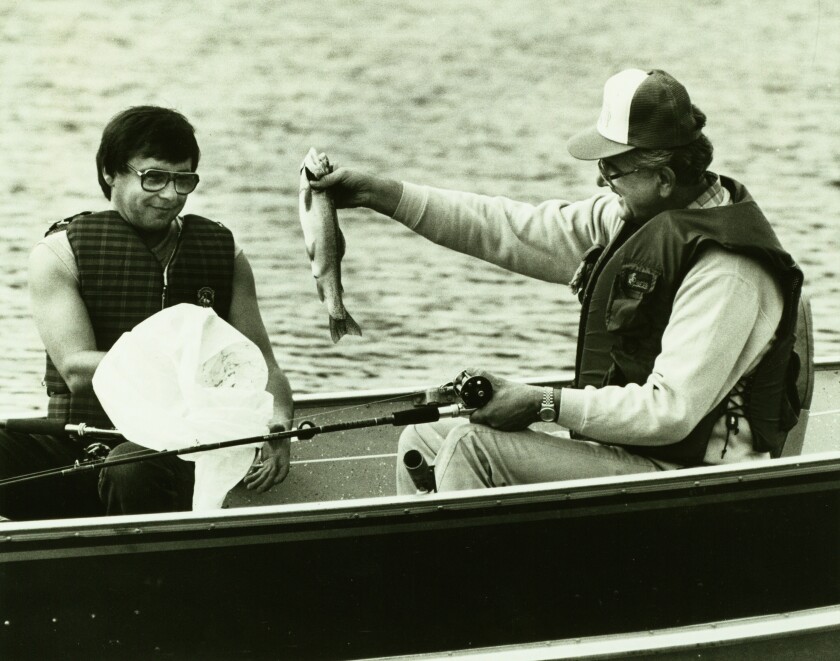

On the morning of Nov. 3, 1982, media converged at Rudy Perpich's cabin on Lake Esquagama, where the newly declared governor-elect demonstrated his northwoods bona fides.

"Posing for two photographers," reported the News Tribune's Ann Glumac, "Perpich hauled wood, lugged his canoe from the lakeshore and shoveled inch-thick snow — all the while commenting on its beauty."

Perpich cut a unique figure, both charismatic and eccentric. "God, he was a handsome dog," Sandy Keith, who was elected lieutenant governor in 1962 with Perpich's support, told Wilson. "Tall, very black hair, a beautiful wife."

ADVERTISEMENT

At the same time, "We knew he was quirky. We knew he was not afraid to rub the establishment (the wrong way)," said Anzelc. "When he got an idea, he developed it and took it as far as he could take it, but he was pragmatic enough to realize when it became hopeless."

"He also was loquacious," Brown said. "If you have a thick Range accent, which is kind of an amalgamation of all the immigrant accents put together, you don't sound like the modulated voices of news anchors or big-city lawyers. He was an Iron Range dentist who talked like an Iron Range dentist."

Perpich's penchant for ambitious concepts, and a persona that could read as offbeat, led to the coinage of a derogatory moniker that stuck. "He was known for his unconventional ideas," wrote the Associated Press in "and some critics even called him 'Governor Goofy.'"

That term was used in the headline of a 1989 Newsweek article that claimed Perpich's "idiosyncratic charm may be wearing thin," attributing the unflattering nickname to Minnesota Republicans. Perpich blamed future Fox News CEO Roger Ailes, then a media consultant, for planting the story; Newsweek denied that was the case.

A more sympathetic way to regard Perpich was as "the people's governor," to quote the term Wilson chose for the subtitle of her 2005 biography, "Rudy!"

"He was always concerned about the needs of the people, always. They were at the center of who he was," said Iron Range historian Pam Brunfelt. "It wasn't just the Iron Range. It was everywhere in Minnesota. He traveled more in the state of Minnesota than any previous governor had, and he was always out and about among the people."

Making Minnesota 'Greater'

There was a time in the state's history when "Greater Minnesota" wasn't a place, it was an aspiration.

ADVERTISEMENT

In the first decades of the 20th century, civic boosters regularly stepped on soapboxes to call for a "greater Minnesota": greater in population, greater in influence, greater in culture. In the 1920s, a Greater Minnesota Association was founded to promote tourism, immigration and general economic development. Newspapers promoted a Greater Minnesota Week, and in 1930, Gov. Theodore Christianson proclaimed a Greater Minnesota Day.

The Depression muted those calls, and new buzzwords eventually took the place of the once-potent "greater Minnesota" message. A few decades later, "Greater Minnesota" had evolved into a geographic designation. When the term occasionally popped up in the 1960s and '70s, it was sometimes used to describe the entire Upper Midwest, in the sense that people today might include Hermantown and Two Harbors in the "greater Duluth area."

By the 1980s, the term was finally coming into widespread use in the sense we know it today, sparking some sardonic observations from metro residents who caught the rhetorical implication. "You stand a good chance of being corrected around the Legislature if you call the nonmetropolitian area 'Outstate,'" reported the Minneapolis Star and Tribune in 1987.

"But if it's Greater Minnesota out there, what is it in the Twin Cities area?" continued the paper's "Inside Talk" report. "Rep. Linda Scheid, DFL-Brooklyn Park, apparently has come up with the answer. She referred to the seven-county area as 'Lesser Minnesota' while talking to her DFL colleagues this week."

"If there's a transition from 'Outstate' to 'Greater Minnesota,' there's some symbolic recognition inherent in that," said University of Minnesota Duluth historian Erik Riker-Coleman last week, reflecting on the change. "It's interesting that that has prevailed, in spite of the reality that in the intervening years, 'Outstate' or 'Greater Minnesota' has become even smaller relative to the population. The state has become more urban or suburban, more centralized than ever before."

High hopes for a reimagined Range

The new name was written into law, in a sense, with the 1987 creation of the Greater Minnesota Corp. A state-funded enterprise, GMC was intended "to help establish permanent diversity and stability for the rural economy," wrote biographer Wilson. By 1989, though, Perpich tired of wrangling with the Legislature over funding for the project and set his sights instead on an independent institute.

GMC looked like a political failure for Perpich, but it became the nonprofit Minnesota Technology, Inc., providing technology assistance to thousands of manufacturers by the end of the 1990s.

ADVERTISEMENT

"He was a futurist," said Anzelc about Perpich. "He never talked about last week, ever."

"He was trying to make Minnesota a big player in international markets," said Brown. "That predated a lot of the globalization that we experienced, and I don't think anyone could call him goofy for thinking that Minnesota should be selling products in the world economy."

Raised to be skeptical of mining companies' promises, Perpich doubted the Range's future could be built on the extraction industries that had fueled its growth.

"You have to keep in mind," said Anzelc, "that the Perpich brothers threw rocks at the Great Northern trains when they were hauling the iron ore off the Iron Range and shipping our wealth out east without paying their fair share in taxes."

"I don't believe he felt confident that his beloved Iron Range was going to be able to keep up, being a natural resource area far from the marketplace," Anzelc said. "He put taconite tax money into projects that he felt would diversify the Iron Range economy, and frankly, he got excoriated for it. ... He tried to make chopsticks; he tried to do a whole host of other things to create jobs."

The state-assisted Hibbing chopsticks plant became a much-discussed experiment, seen by some as emblematic of Perpich's laudable aspirations to diversify the Iron Range economy and by others as a quixotic boondoggle. Cal Ludeman, Perpich's Republican opponent for reelection in 1986, "ran television and radio ads lampooning the chopsticks venture," wrote Wilson, "showing people with chopsticks fumbling with fried chicken and Jell-O."

Perpich won that election, but the plant closed in 1989, its owners unable to compete in the Asian marketplace with Chinese plants using much cheaper labor. "I always point out that at least for a time, the chopsticks factory did produce chopsticks," said Brown. "You look at economic development proposals now, and quite often you're talking about millions of dollars changing hands and it's all prospective. Nothing ever actually happens of it."

ADVERTISEMENT

End of an era

A recurring theme in accounts of the Perpich era is the governor's complex challenge as a transitional figure in Minnesota history. A product of the rapidly-passing era of labor power on the Iron Range, Perpich pointed to a future of technology and trade that didn't arrive soon enough for him to welcome it, and might never bear the benefits he hoped to see the Range reap.

Riker-Coleman pointed to an observation by the late Hy Berman, one of Minnesota's most knowledgeable historians. In Berman used the word "tragic" to describe the situation Minnesota's pro-union governor found himself in during the 1985-86 Hormel strike.

"He didn't have any options," explained Berman about Perpich calling in the National Guard to keep the Austin meatpacking plant open. "He, as governor, was honor-bound to call out the Guard in case there was a breach of the peace in the state that couldn't be handled by local authorities, and the local officials requested it." The result, in Berman's view, was Perpich symbolically presiding over a historic labor loss caused by forces beyond the governor's control.

Perpich lost his shot at a third term in the 1990 election, a race upended by accounts of Republican nominee Jon Grunseth trying to pull a swimsuit off of a teenage girl at a 1981 pool party. State Auditor Arne Carlson took Grunseth's place in the race, creating a political matchup that would be unimaginable today: an economically liberal Democrat who was anti-abortion (Perpich, the first and still the only Catholic governor of Minnesota) facing off against a moderate Republican who was pro-choice (Carlson, taking a position that increasingly put him at odds with his own party).

"Carlson was arguably the more socially liberal candidate in that race," said Riker-Coleman, noting that Carlson also supported gay rights initiatives. Perpich, Riker-Coleman explained, "really represented the early 20th century farmer-labor roots of the DFL tradition, more so than a later 20th century pluralist cultural liberalism."

(Contacted by the News Tribune, Carlson declined to comment for this story, saying that as a former political opponent, it would be inappropriate for him to assess Perpich's legacy.)

While Perpich seriously mulled another comeback attempt in 1994, he ultimately declined to challenge Carlson's successful reelection bid. Perpich would die of colon cancer just a year later, in 1995.

'Kind of a visionary guy'

"Everybody tends to remember the version of Rudy that they want to remember," reflected Brown, noting that some people remember Perpich as a unifying moderate, while others cite his economic liberalism. "Today, people remember how it felt to have an Iron Ranger as governor, and they liked that feeling, even if they may or may not have agreed with his politics."

"I was in college. I graduated from Virginia High حلحلآ» in 1975," remembered Brunfelt about Perpich's rise to the state's highest office. "I was so proud of him. He was such a whirlwind of energy, and he made the state what it became. He never forgot where he came from, he never forgot how important education was."

"He was kind of a visionary guy," Brown said. "You can look back at a lot of the things he was called 'goofy' for, the Mall of America and some other things, and say that, you know, they did have some staying power."

"The press and the government laughed at him when he said he wanted to bring Gorbachev to the Twin Cities," said Brunfelt, "and by God, he pulled it off."

"When you look at what is working and the new businesses around the country," said Brown, "these businesses that have grown since Rudy Perpich was governor, you're looking at companies that have exploited the idea of selling on world markets and treating the world as one big customer base, not as separate nations. And I think that's what Rudy was trying to talk about, too, in his thick Iron Range accent that not everybody took very seriously."

"Among Range people, among Minnesotans, they accomplished so much," said Anzelc about the Perpich brothers. Anzelc recalled Rudy Perpich citing an ethnic slur that was sometimes used against Central European immigrants. "He would say to me, because I'm the son of immigrants as well, 'Sometimes they think that I'm just a dumb hunky. But I'm not. I'm going to be governor.'"

"He was a Minnesotan through and through," said Brunfelt. "He was proud of the state, and he was proud of what we accomplished, and he wanted people to know that there was more to the state than the Twin Cities."