DULUTH — As kids growing up in Duluth in the 1980s, my siblings and I desperately wanted to go to the revolving restaurant at the top of the Radisson. My mom decided to use it as an incentive: We could go to the top of the Radisson, she said, when we had "top-of-the Radisson manners."

When we started to get squirrely at the table, Mom would remind us. "Kids!" she'd say. "Top of the Radisson!"

ADVERTISEMENT

The restaurant was an unusual feature even then; today, it's downright rare. A indicates the United States has only about 15 revolving restaurants that are still operational and open to the public for regular dining service.

You won't find one in Chicago, Houston or Philadelphia. St. Paul's revolving restaurant ground to a halt in 2006. In Duluth, though, the restaurant now called the Apostle Supper Club still takes diners on a 72-minute, 360-degree circuit.

On Thursday, Jan. 12, I crossed Fifth Avenue West, and pressed the "R" button on the Radisson elevator. Seated at a hightop table near the outside edge of the restaurant's ring, I looked out at the slowly passing skyline and wondered why we Duluthians don't make a bigger deal about our revolving restaurant.

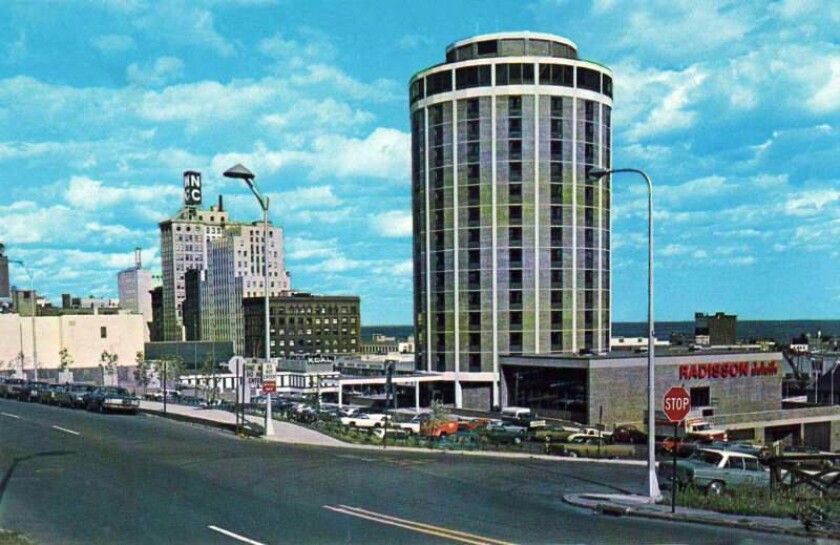

When the Radisson Duluth Hotel opened in 1970, readers of the News Tribune's opinion page might have thought the city was opening a cathedral. "As much as the new Radisson Duluth is bricks and mortar, glass and steel, it is spirit," read a May 29, 1970, editorial. "This new hotel is a commitment of a generation of this city."

You couldn't blame the paper for being excited. The new hotel, with its radical restaurant, was a crown jewel of the decade-plus Gateway Urban Renewal Project, which cleared a wide swath of what was known as Duluth's "bowery" neighborhood. Goodbye, taverns and flophouses. Hello, Minnesota's tallest cylindrical building!

"Troop pullouts grind to halt in South Vietnam" read the News Tribune's top headline on the day "a special gold-plated scissors" was used to cut the Radisson ribbon. General Manager Clark Dohm opened the front doors with a key that he then, in dramatic fashion, threw away to indicate that the hotel was permanently open. It was downtown Duluth's first new hotel in over 40 years.

"It WAS love at first sight" for the hotel's first guests, a front-page feature story declared. "The Radisson Duluth is replete with a year-round heated swimming pool and a 16th floor revolving restaurant that will make a full spin of the Duluth skyline and harbor every 60 minutes."

ADVERTISEMENT

The Apostle Supper Club, which opened on the Radisson's top floor last spring, harks back to the 1960s rather than the '70s. Although the decor is slightly anachronistic for Duluth's Nixon-era revolving restaurant, the Kennedy/LBJ years saw the peak point of excitement for revolving restaurants.

Much of the music I heard during dinner last week was released around the time Seattle wowed America with its iconic Space Needle. Built for the 1962 World's Fair, Seattle's tourist tower featured a restaurant called Eye of the Needle, advertised as revolving with such suavity that "it won't even ripple a martini."

That wasn't the world's first revolving restaurant; Germany opened one the preceding year. As far back as the Roman Empire, in fact, Nero had that archaeologists believe turned on a mechanism powered by water flowing from aqueducts.

For the game of Civilization being played by Duluth developers in the '60s, a revolving restaurant was a sign of sophistication — and a way to showcase our shoreline long before the Lakewalk and Bayfront Festival Park came into being.

"Revolving restaurants were prestigious symbols of arrival," wrote historian Chad Randl in his 2008 book "Revolving Architecture." Randl links revolving restaurants' popularity to the breathless technological optimism of the space race. Duluth's Radisson opened for business less than a year after humans first set foot on the moon.

"Designers sought to make visitors feel, if only for an hour, that they were part of an advanced age," Randl wrote. Diners felt "they were leaving the present behind and stepping into a privileged tomorrow."

The Radisson's restaurant still offers a unique window on Duluth's expansive industrial infrastructure. On Jan. 12, the red lights of the antenna farm blinked across the sky like UFO landing beacons. When my table turned to face the harbor, I watched the thousand-foot laker James R. Barker execute a neat turn before gliding under the Aerial Lift Bridge. The vessel's awesome size was particularly apparent at night, its lights spanning the length of three city blocks.

ADVERTISEMENT

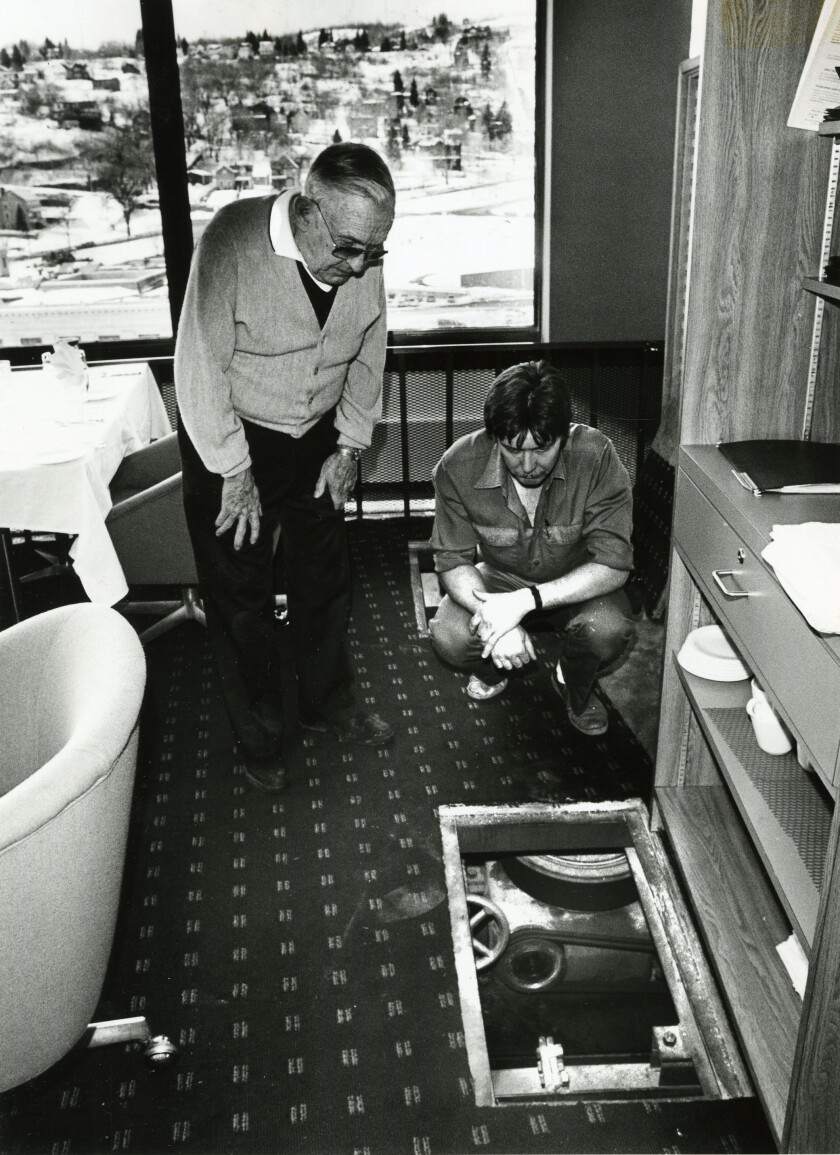

It was impossible to miss Elvis Presley in the music mix. The King stayed at the Radisson in 1976 and 1977, becoming the establishment's most famous fan. The latter year saw the hotel expand, adding 60 rooms and a parking ramp. Over the years, the hotel has seen multiple renovations and infrastructure upgrades, including the 1999 addition of a "Skunnel": the portmanteau designating a skywalk tunnel connecting the hotel to the Duluth Public Library.

The restaurant was the site of a dinner date in last year's holiday movie "Merry Kiss Cam," though its rotation was turned off during filming for the sake of continuity. The filmmakers behind 2017's "In Winter" kept the restaurant spinning for a surreal effect, but the scene they shot there didn't make the final cut.

The former Top of the Harbor restaurant became JJ Astor in 2010, surviving the pandemic but closing in 2022 as Purpose Restaurants came in with the tropics-themed Apostle Supper Club. “We wanted this to feel very vibrant, very summery,” owner Brian Ingram said at an opening event. “Our menu kind of reflects that.”

While I watched Duluth slowly slide by Jan. 12, I enjoyed an order of pickle-brined fried chicken with skin so thick and rich that the meat was essentially a side dish. I peered into the windows of the Maurices headquarters and down into the stacks of the public library. I caught glimpses of the Depot's Great Hall, and watched lines of cars snaking up Mesaba Avenue.

The ride was as smooth as Seattle's Space Needle once promised, an occasional creak the only audible indication that my table was advancing at the rate of about 1/20th mph. "Sometimes I wish it went faster," said my server. Personally, I was fine with it. No need to strain the mechanism of Duluth's midcentury marvel.

The novelty of revolving restaurants was already starting to fade by the time Duluth's Radisson opened. Just four years later, a similar venue built in Bloomington, Minnesota, became an office instead when no restaurateur would take the lease. America's culinary culture was becoming more sophisticated, and diners were losing interest in novelty restaurants where the food was often priced well above its quality.

Duluth's revolving restaurant may no longer be particularly on-brand, and you may or may not find the food to be worth the splurge, but the next time you're extolling our city's attractions, spare a thought for our most spectacular vestige of the space age: a beacon of progress during a couple tough Duluth decades when inspiring signs were few and far between.

ADVERTISEMENT

This is a city that takes care of its history. Our trains still roll, our bridge still rises, and even The NorShor Theatre, which was showing "A Man Called Horse" when the Radisson opened, has been restored to newfound glory.

On top of all that — literally — Duluth is one of just over a dozen cities in America where you can walk into a restaurant and be asked a question like the one I heard when I emerged from the elevator Jan. 12, wearing a sportcoat and marshaling my very best top-of-the-Radisson manners.

"Would you like to be at the bar," the host inquired, "or would you like something rotating?"