Could climate change turn Minnesota into Kansas?

Lee E. Frelich, director of the University of Minnesota Center for Forest Ecology, addressed this question during his presentation on Saturday, Sept. 13 at Itasca State Park in Park Rapids, Minnesota.

ADVERTISEMENT

Frelich explained that the park lies near the convergence of three biomes: boreal forest, temperate forest and prairie.

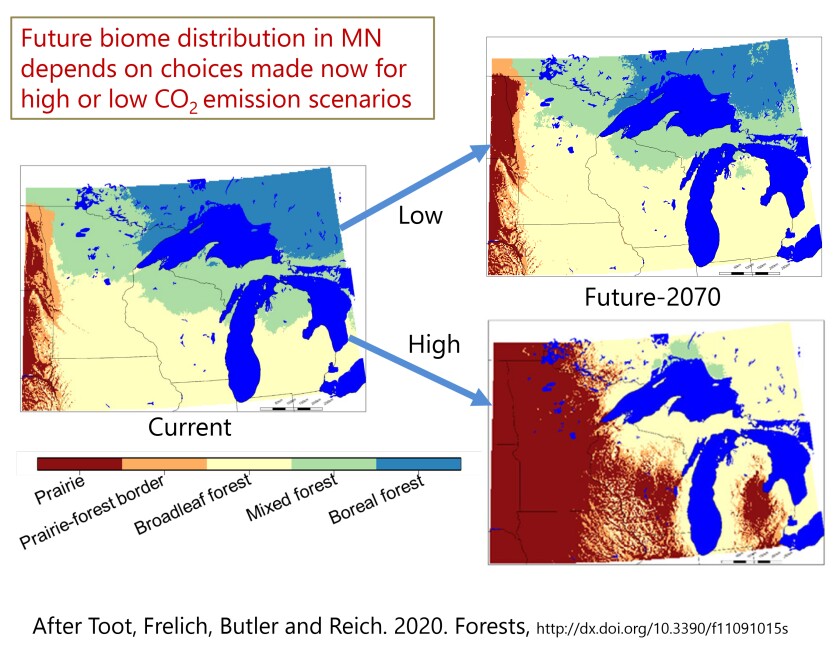

Scientific research is exploring how those biomes could shift in low- versus high-warming scenarios.

A 9- to 10-degree increase in summer mean temperatures “would make this place like north-central Kansas,” he said, whereas a 4- to 5-degree increase will change the landscape to something similar to Granite Falls, Minn. Frelich said Itasca State Park would then become “prairie, with light vegetation” between oaks.

“There’s a few preliminary indications that maybe we’ll be able to avoid the high scenario, but if we look at the high scenario, we would expect all of our tree ranges to shift north by about 300 miles,” he explained.

“Minnesota is the edgiest state in the union,” he continued, adding almost every tree species native to Minnesota has its range limit in the state.

When summer mean temperatures are between 64 and 65 degrees, both boreal and temperate saplings grow equally well in northern Minnesota, Frelich said.

A study has shown, he said, that as summer temps rise, temperate species thrive. Examples are bur oak, red oak, basswood, sugar maple, red maple and yellow birch.

ADVERTISEMENT

This means Itasca Park would lose boreal species, like black spruce, white spruce, balsam fire, jack pine, red pine, quaking aspen and paper birch. Boreal species prefer cooler summer averages, below 59.5 degrees.

Temperate forests are already “invading the understory of boreal forest” in Minnesota and Wisconsin, according to Frelich.

“It’s pretty strong here,” he said of the park’s region, but not as strong as what’s happening in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area.

Another study found that “precipitation minus evapotranspiration” is the most important factor in transitioning from forest to grass.

“In other words, if it rains more than the water evaporates, you get forest. If there’s more evaporation than precipitation, then you get grassland,” Frelich explained.

The prairie forest-border depends on whether the soil is sandy or silty or near a large body of water, he added.

By 2070, Minnesota could see more prairie push into the western part of the state as mixed-boreal forest recedes in the low CO2 emission scenario. In the high emissions scenario, Minnesota could convert to 90% prairie, Frelich said.

ADVERTISEMENT

It’s not too late to decrease CO2 emissions, he noted. He suggested the following:

- Eat more plants.

- Use more energy-efficient cars and buildings

- Stop deforestation

- Plant trees and restore the natural ecosystem.

Loss of conifers to insects, fire, wind

Summers have become wetter, Frelich said. While the annual average precipitation is up, ”it’s much more unevenly distributed. You get a big flood, then you don’t rain for a couple months.”

Insect infestations become more common because trees are unable to acclimate to the fluctuating moisture and defend themselves, he said.

Norway or red pines are particularly hit hard by fungal diseases, as an example.

Wind storms and fire are expected to be more common in a warmer climate, possibly accelerating change, he explained.

Very early, warm springs also “upset the mechanisms that trees have for deciding when to come out of dormancy,” Frelich said, citing the impact of a record-high spring in March 2012. This is called “phenological disturbance.”

When trees bloom too early, they may all die at once, he noted.

ADVERTISEMENT

Between 2041 and 2070, the number of weeks per year with fire risk is anticipated to increase 600% in northeastern Minnesota.

In Canada, 45 million acres burned during the 2023 fire season, according to Natural Resources Canada. That was 5% of all forest in Canada compared to the average of 5.1 million acres, or 0.6%, from 1983 to 2022.

If contemporary fires are too intense or too frequent, Frelich said “legacy-lock” boreal conifers will die where they had been dominant for 7,000 to 10,000 years. They will be replaced by oak, birch and aspen. This is happening in Minnesota, Alaska, Saskatchewan, Russia and Scandinavia, he noted.

Indigenous people in Minnesota are conducting prescribed burns under red pine forests to preserve that legacy-lock. In Cloquet, Frelich said, the Fond du Lac Nation did a burn to remove ladder fuel. It’s “the best hope” for saving red pines, he said, like those in Preacher's Grove at Itasca State Park.

As northern Minnesota’s forests change, wildlife will change with it, he added.