DULUTH -- In the fall of 1941, just before the U.S. entered World War II, hunters in Minnesota went afield and shot 1.8 million pheasants, the most ever.

That was just 25 years after the birds, natives of China, were successfully introduced to the state in 1916, and only 17 years after the first Minnesota pheasant hunting season was held in 1924.

ADVERTISEMENT

It was an amazing explosion of upland game and hundreds of thousands of people took advantage of it by hunting the colorful ringnecks, days when the Minnesota pheasant opener rivaled the deer and walleye openers for interest among the public. There were up years with dry, mild summers and some down years with heavy snows or spring blizzards. But the number of pheasants and hunters stayed pretty steady once the troops returned from WWII.

In 1956, Minnesotans shot 1.04 million pheasants. And in 1961, 270,000 pheasant hunters went afield in Minnesota and shot 1.3 million birds.

Flash forward to 2018, however, and a vastly changed Minnesota agriculture landscape had squashed those numbers to a fraction of their highs: Only 45,000 hunters went afield and managed to harvest only 172,000 roosters. (It’s not just a Minnesota problem. South Dakota hit a peak pheasant harvest of 7.5 million in 1945 and had dropped below 1 million by 2013.)

What went wrong?

In a word, farming. Millions more acres of row crops added over the last 70 years — mainly corn and soybeans — has meant millions fewer acres of habitat where pheasants and other wildlife can live year-round.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 1941, Minnesota farmers planted 4.7 million acres of corn and soybeans, federal agriculture statistics show. By 1956, that had nearly doubled to 8.5 million acres. By 2018, Minnesota farmers planted 15.6 million acres of corn and soybeans — up 11 nearly million acres since 1941.

Some of those 11 million acres were converted from other crops, like wheat. But many acres were previously unplowed pasture, hayfields, fencelines, hilly land, ditches and other grasslands — as well as wetlands, thousands of acres of wetlands drained and plowed — that had been habitat for pheasants, butterflies, songbirds and other wildlife. Department of Agriculture data shows there are a combined 6.5 million more acres of all major crops they track now than in 1941.

RELATED: Read more hunting stories on Northland Outdoors

Other farming changes are involved. Pesticides that kill crop-eating bugs also kill the bugs that pheasant chicks depend on. And herbicides that kill weeds and improve yields, allowing far more crops to be grown on each acre, have rendered cornfields less suitable for wildlife.

“When I’d hear my grandpa talk about shooting all those pheasants in the old days he always talked about how weedy the cornfields were — big foxtail and other weeds,’’ said Greg Hoch, prairie habitat supervisor for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. “Now, the fields are so clean, it’s hard to find a weed.”

ADVERTISEMENT

More food and fuel, less wildlife habitat

Minnesota farmers are helping feed and fuel the world — making beef cattle and hogs fatter, producing corn syrup for our soft drinks, ethanol to run cars and soybean oil that powers diesel trucks — at a pace unparalleled in the past. But the price has been far less wildlife habitat. Most row crops cover the land only in summer and fall until harvest, and then plowing leaves a black dirt landscape void of wildlife habitat until the next spring. Winter and spring habitat is critical for wildlife survival.

Tim Lyons, Minnesota DNR upland game research scientist, said the trend to far fewer but far larger farms, and toward more cash-crop farms and fewer dairy farms, has contributed to the decline in grassland as farmers converted pastures, hay and oat fields to corn and beans. (In 1941, Minnesota farmers planted 4.2 million acres of oats that often remained on the land through winter. By 2018, that dropped to just 180,000 acres.)

“There’s been a huge change in the landscape over the years. It’s not just the size of farms, but the type of farms,’’ Lyons said. “We went from having millions of acres that were covered year-round to millions of acres that are bare ground and black every fall and winter.’’

While weather and predators have an impact on pheasants and other farmland wildlife, they mostly account for annual blips in populations, often more local than regional, biologists say. The worst impacts of a blizzard or ice storm usually hit over several counties. But there is an uncanny correlation between how much habitat is on the landscape statewide and how many pheasants are there.

In the late 1950s, the federal Soil Bank program of the Eisenhower administration saw millions of acres of land taken out of crops nationally and restored to grass. The program led to an almost immediate upswing in pheasants, with an average of 1 million shot in Minnesota through the 1960s.

That lasted until the program fell out of favor, replaced with a Nixon administration policy in the 1970s encouraging farmers to pull up their fences, plow their back 40s and plant every inch of land they could. The U.S. was going to outproduce the Soviet Union and feed the world. And Minnesota pheasants plunged to an average annual harvest of just 200,000 in the 1970s.

Farmland wildlife and the people who pursue them received a gift in 1985, when the federal farm bill included a provision to pay farmers across the U.S. to not plant crops on up to 40 million acres. Hundreds of thousands of farmers enrolled in the new Conservation Reserve Program aimed at reducing a surplus of commodity crops, reducing soil erosion, improving water quality and increasing wildlife habitat.

ADVERTISEMENT

It worked better than anyone could have expected. As more Minnesota farmers enrolled, more pheasants were produced. In 2007, Minnesota had 1.83 million acres enrolled in the federal CRP program and 118,000 hunters bagged 655,000 roosters, the most in more than 40 years.

It didn’t take long, however, before Congress and many farmers lost interest in CRP when corn prices were skyrocketing. Nationally, enrollment in CRP dropped from more than 37 million acres in 2007 to 24 million by 2012, more than 13 million acres of habitat lost — much of it in prime pheasant range — an area the size of New Jersey and Connecticut combined.

More habitat, more pheasants, more hunters still possible

By 2015, Minnesota was down to 1.1 million acres of CRP and just 63,000 hunters bagged 243,000 birds. The 700,000 acres of habitat lost over just eight years saw hunter numbers cut in half and birds bagged cut by 62%.

“That shows you how farm policy, habitat, tracks with pheasant numbers,’’ Hoch noted. “That period — 2006, 2007, 2008, those high CRP years — were really the glory days for most Minnesota pheasant hunters who are still active.”

But Hoch and others say Minnesota can get back to the glory days for pheasants. Probably never the 1940s or '50s, but maybe back to 2007 levels of habitat and birds.

ADVERTISEMENT

“That’s sort of our goal. Maybe 750,000 (roosters harvested annually) is attainable if a lot of things come together at the same time — farm policy and weather. But I don’t think we could ever get back enough habitat to get to 1 million pheasants shot in Minnesota again,’’ said Eran Sandqusit, Minnesota coordinator for Pheasants Forever, a nonprofit group aimed at increasing habitat for wildlife. “The good news is that we know the answer. We know how to get there. We just need to get more grass and flowers on the landscape, and make the grass and flowers we have now more productive, and the birds will follow.”

Over the last decade, Pheasants Forever has been buying about 4,000 acres of land annually to set aside for habitat and hunting in the state. The state of Minnesota, using Outdoor Heritage Fund sales tax revenue and other money, has been buying up to 10,000 acres annually for new and expanded wildlife management areas. But over the same period, the state was losing 100,000 acres of habitat annually as farmers pulled out of CRP.

The 2018 Farm Bill increases the CRP cap from 23 million to 27 million acres nationally by 2023 — good news for habitat, but still far short of the 35 million acres conservation groups had lobbied for. That’s added about 10,000 acres of habitat back in Minnesota, but still far short of the 2007 level.

State efforts are trying to make up for the loss of CRP grassland. The state’s Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, Reinvest In Minnesota program and Wetland Conservation Act all offer funding to buy easements or permanent title to agricultural land to convert it to habitat. But pheasant supporters say it won’t be until Congress becomes more conservation minded that farmland wildlife will fully bounce back. It’s a tough row to hoe with ag industries lobbying for more crops.

“Until we see a major increase in CRP we'll just see incremental change in pheasant numbers,’’ Lyons said. “DNR and the (conservation organizations) are pulling all the levers we can. But it’s just a fraction of the acres the federal government can bring in.”

ADVERTISEMENT

In the meantime, Pheasants Forever biologists and agronomy experts, as well as state and local soil conservation officials, are working with farmers to show them which of their acres are most profitable and which acres they plant are actually losing money because fertilizer, fuel, pesticide and other costs are so high. One Iowa study estimated 10 million acres across that state that farmers currently plant in corn and soybeans are costing the farmers more money than they make selling the crop.

“It’s 10 acres here, 20 acres there … But imagine, across a state, it could really add-up,’’ Hoch said. “That could be millions of acres in Minnesota, too, taken out of production and put back into grass, helping the farmer’s bottom line, helping flood control and soil conservation, and really helping wildlife.”

Pheasants Forever in recent years has pivoted its focus to concentrate more on private land, which is the vast majority of acreage in the pheasant range, working with farmers to keep grass on their land. Sundquist said seemingly simple changes in agriculture tactics, like waiting until spring to remove last year’s crop residue and to plow, could make a difference for wildlife. While many farmers say they plow in the fall to speed spring drainage, some studies show land that’s left covered over winter often filters spring runoff faster than black dirt.

And Sundquist said elected officials and policymakers need to rework agriculture policy to encourage conservation, like filter or buffer strips near waterways, rather than simply more production.

“It seems like we’re producing more corn and beans than the world needs, and we’re driving the price down, which doesn’t help the farmer any,’’ he said. “Let’s farm the best and buffer the rest.”

Hoch said the benefits of more farmland wildlife habitat can help bolster the rapidly declining number of pollinators, bees and butterflies, across the region. And grassland habitat can help people, too, filtering nitrates out of water, storing carbon to slow climate change and reducing flooding.

In Worthington, the city was running out of clean water from its well. One answer would have been to spend millions of dollars to pipe water in from far away. But the city instead purchased farmland on top of the drainage area that seeps into its well. More than 500 acres of the most vulnerable soils in a water-well protection area were purchased and converted to grasslands, which reduces erosion and runoff and helps conserve water while providing habitat for pheasants and other wildlife. Another 900 acres of nearby land also have been protected.

“People call me the DNR pheasant guy, but really a lot of my time lately has been on pollinators,’’ Hoch noted. “There are so many societal benefits when we restore habitat, restore grass to the landscape. It’s not just pheasants that benefit.”

Minnesota 2020 pheasant season

- Starts: Oct. 10

- Ends: Jan. 3

- Hours: 9 a.m. to sunset

- Limit: Two roosters daily until Nov. 30; three daily after that

- Resident small game license: $23

- Pheasant stamp: $7.50

- Walk-in access validation: $3 (Allows access to 30,000 acres of private land enrolled in program.)

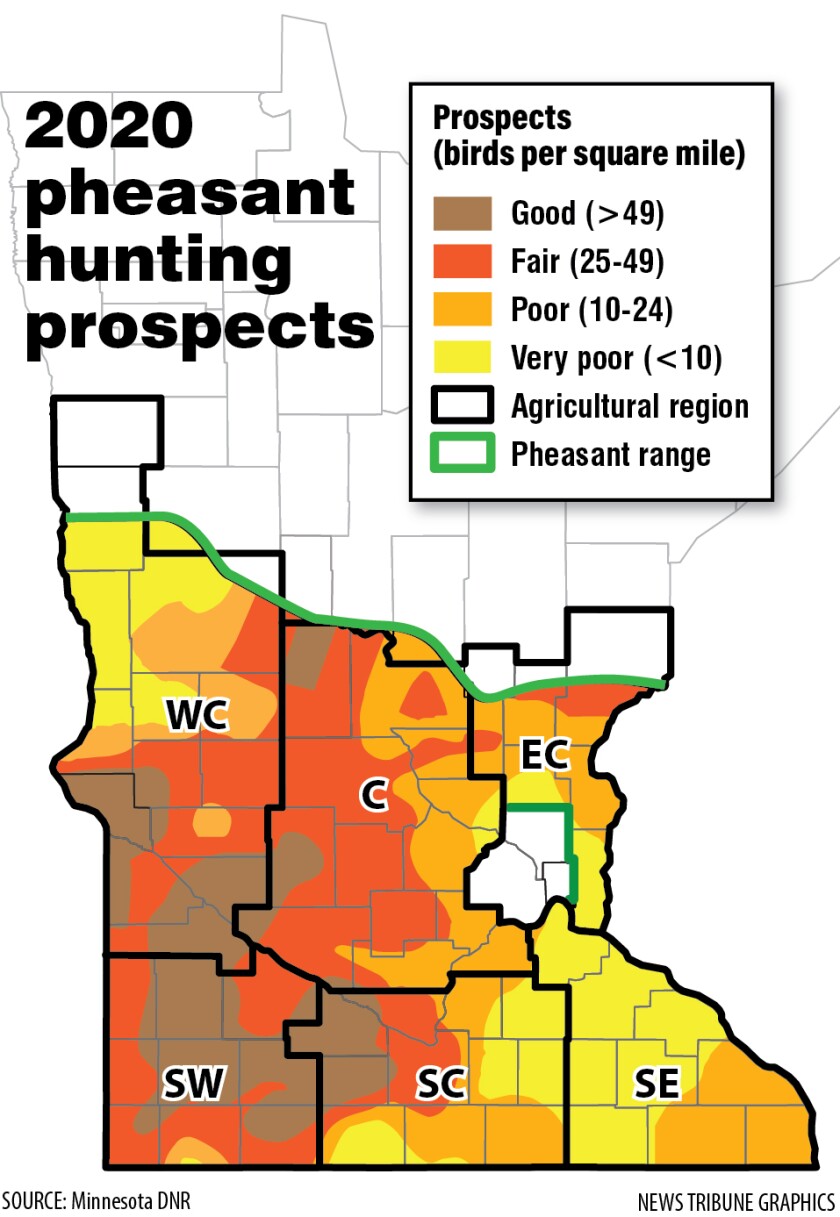

- Outlook: Better than last year, with roadside surveys showing a 42% increase over 2019 and 37% over the recent 10-year average. The best areas are the southwest and east-central counties.

- Perspective: The 53 birds counted per 100 miles on average this year is a fraction of the more than 300 birds per 100 miles counted in the 1950s and about half the recent highs of over 100 birds per 100 miles as recently as 2007.

For more information: