GRAND RAPIDS — A four-year study into northern Minnesota’s little-known spruce grouse population has found the birds are still part of a genetically healthy, interconnected population that’s not yet isolated by declining pockets of habitat.

That's good news for the bird that lives in dense forests of conifer trees — black spruce, jackpine and balsam fir — across the state’s northern tier of counties, mostly north of U.S. Highway 2.

ADVERTISEMENT

Because the bird lives in such wild areas, and in habitat often too dense for people to even walk through, the bird has been studied very little over the years.

But a joint effort by scientists at the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, the University of Minnesota and the University's Raptor Center — with help from the state’s grouse hunters — has found the birds are still in generally good shape even as their habitat contracts north.

“There is still a fairly large, interconnected population of spruce grouse in northern Minnesota,” said Charlotte Roy, grouse research biologist for the DNR. “The takeaway here is good news.”

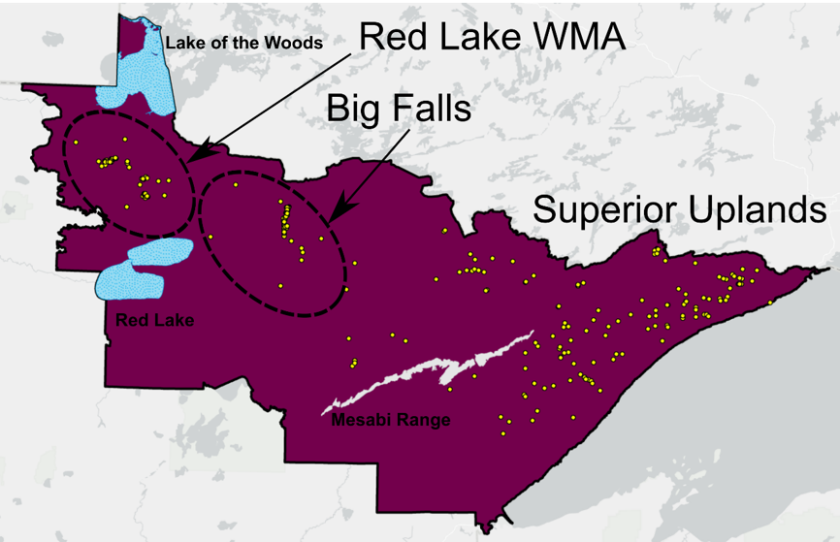

The study, with results just coming out, looked at both spruce grouse range, based on how many and where their droppings were found, but also spruce grouse genetics based on tail feather samples collected by hunters and turned in to the DNR, and by grouse that were being monitored with radio telemetry at two locations: the Red Lake Peatlands and state forests in Koochiching County near Big Falls.

Grouse hunters sent in 158 tail feather samples over several seasons, with the feathers used to track the gene pool.

Another part of the effort sent wildlife biologists across northern counties into the woods late each winter to count spruce grouse poop pellets on top of snow, a move intended to determine both the current range and, to some extent, population density. It was the first time the DNR figured out a reliable way to tally the birds that don’t drum like ruffed grouse, don’t vocalize like songbirds and aren't seen out in the open enough to accurately count visually like pheasants or ducks.

“It turns out that in late winter, early spring you can find that stuff everywhere,” Roy said of spruce grouse poop. “Assuming there are birds in the area.”

ADVERTISEMENT

In coming years, the poop pellet index could be used to determine whether the population is increasing or decreasing in any given area, although it’s too soon to tell now. Biologists have no clue how many spruce grouse are in Minnesota, although they are sure that the bird has moved out of north-central Minnesota, probably due to declining habitat.

Fifty years ago, reports of spruce grouse in north-central Minnesota and even south of Duluth were common. But not anymore.

“We don’t have any reports and didn't get any tail feathers, from anywhere south of Duluth. About the farthest south was maybe the Leech Lake or Cass Lake areas,” Roy said.

A map of where tail feathers were collected shows nearly all were taken in Cook, Lake, northern St. Louis, Koochiching and Lake of the Woods counties where dense conifer stands are still common.

Spruce grouse have declined so much in Michigan and Wisconsin that hunting them is no longer allowed there, and the birds are on those states' lists of protected species. Oregon, too, stopped hunting them 45 years ago due to population concerns.

In Minnesota, spruce grouse aren’t nearly as popular among hunters as ruffed grouse or pheasants. But hunters here have harvested anywhere from 7,000-19,000 spruce grouse each year for the past 13 years, Roy said, an estimate based on surveys mailed to hunters. That's more than sharp-tailed grouse in most years.

ADVERTISEMENT

Forest habitat is key to bird’s future

While it’s unknown if warmer temperatures have a physical impact on spruce grouse, scientists have noted the birds tend to range farther to find mates — a good thing — during years with colder springs.

It’s also expected that spruce grouse habitat, sub-boreal forests, is expected to retreat rapidly north — mostly out of Minnesota — as temperatures and precipitation patterns shift. That has scientists concerned that lack of conifer habitat may be an issue for the bird in coming years.

Audubon Society scientists have used computer models to simulate future conditions across spruce grouse range in North America. They found that warming temperatures under climate change could lead to an 84% reduction in spruce grouse habitat across the continent, pushing the birds out of the continental U.S. entirely and leaving suitable habitat only in Canada.

The key for the bird's future in Minnesota, Roy said, is for foresters to manage the land to include large, connected blocks of very dense conifer forest, not always the most desirable for other forest demands like the wood products industry. That dense forest provides not only food but also roosting habitat, including thermal cover from the coldest nights of winter, as well as places to hide from predators like hawks.

The study results “indicated that forest management practices that promote dense vegetation structure may benefit spruce grouse, especially a dense mid-canopy layer,” researchers concluded. Thick evergreens 15-50 feet tall are best. “Forests that are difficult for people to walk through … and for goshawks to fly through,” Roy added.

The study found that spruce grouse have lower survival after timber harvest, but that may be due to indirect effects of timber harvest, such as harvest-related changes in predators — such as increased predators near logged areas — rather than habitat loss.

With decreased conifer forest expected as climate change intensifies “climate change could potentially threaten the persistence of the single interconnected population.”

ADVERTISEMENT

How can spruce grouse be helped to continue thriving?

“We suggest that forest management to promote dense understory structure in boreal forest may provide climate (refuge) for various species of early successional forest wildlife” like spruce grouse, the study concluded.

Other key researchers on the project included Julia Ponder, director of the university’s Raptor Center, and Cody Aylward, a former postdoctoral scientist at the University of Minnesota. The spruce grouse research was funded by the DNR and by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources with dollars from the Environment & Natural Resources Trust Fund, which gets money from the state's lottery profits.

About spruce grouse

- Size: 16-19 inches long, just over one pound — similar in size and shape to the ruffed grouse.

- Coloration: Black, gray and brown banded with white. Darker than ruffed grouse; head is a colorful mix of red, yellow and white, especially during the spring mating season.

- Sounds: Both sexes make a soft clucking sound. Females make a soft territorial cantus call in spring that attracts males to display.

- Nesting: Spruce grouse mate in April or May. Hens lay up to 12 eggs on the ground that hatch in 24 days. Chicks can fly in two weeks but stay with their mother for about three months.

- Food: Spruce, balsam and jack pine needles and buds. Young birds eat mainly insects in summer.

- Winter survival: Prefers to roost nightly in deep snow but will settle for thick conifers that can provide thermal cover and cover from predators.

- Predators: Great horned owls, goshawks, martens, fisher and foxes. Some hunters pursue them but most are taken incidentally by ruffed grouse hunters.

- Nicknames: Spruce hen, fool's hen, fool's grouse because they often are not wary of people and don’t fly when people approach. But researchers say that's not because they are stupid; they just live in dense evergreen forests and don't get attacked by predators very often.

- Hunting: The season and limit is the same as ruffed grouse and runs through Dec. 31. A daily limit of five birds of either type, combined.

- Table fare: Some people insist the spruce grouse meat has an off-taste, like pine needles, while others argue it tastes just as good or better than ruffed grouse.

Source: Minnesota DNR, Audubon