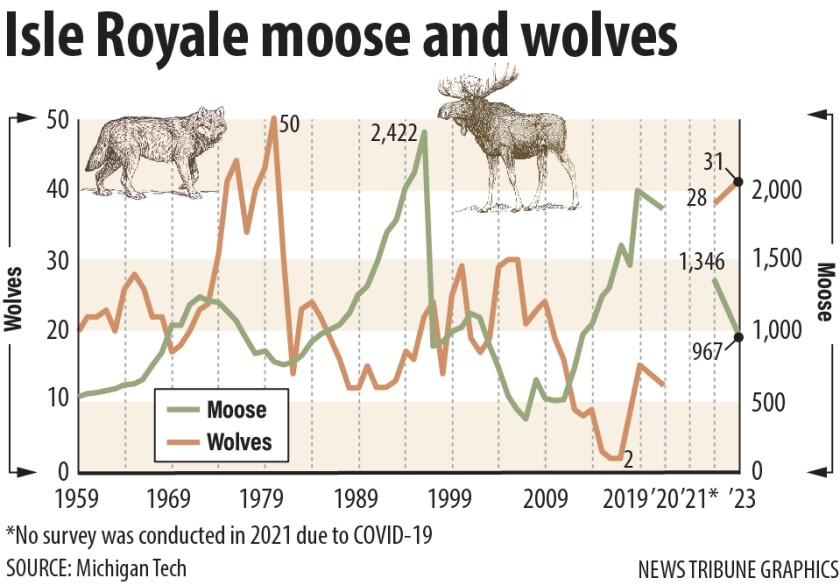

HOUGHTON, Mich. — Isle Royale’s transplanted wolf population continues to grow while the island’s moose population continues to starve and crash.

Those were the findings released Wednesday from the 64th annual winter survey held earlier this year by researchers from Michigan Technological University. It’s the longest-running research project on predator-prey relationships in the world.

ADVERTISEMENT

The survey estimated that 31 wolves live on the island, up from 28 last year. The moose count was 967, down 28% from 2022 and down 54% from two years ago — two of the steepest annual declines ever in the study.

The survey doesn’t include any new wolf pups or moose calves born this spring.

Of the 31 adult wolves on the island, all but two were likely born there, descendants of the 18 wolves transplanted on Isle Royale in 2018 and 2019 after being trapped and transported from Minnesota, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and several Ontario islands in Lake Superior.

“The reproductive success of the wolf population has steadily increased over the last five years,’’ said Sarah Hoy, a lead researcher on the project for Michigan Tech. At least three groups of wolves had new pups in 2022 that survived into winter.

Hoy said the current 31 wolves “are a great number of wolves for the island, it’s a fantastic recovery,’’ she told the News Tribune. “They have formed packs, they are killing moose, they are breeding successfully. Everything suggests the wolves are doing well, especially compared to five years ago when we had just two wolves that couldn’t reproduce.”

The dramatic and somewhat controversial National Park Service effort to bolster the wolf population came after the island’s native population had dwindled to just two wolves due to inbreeding and reproductive failure.

Wolf numbers reached a high of 50 in 1980 but fell to just two by 2016 that were unable to successfully mate. Climate change, spurring far fewer years of ice bridges between the island and the mainland, reduced the number of new wolves venturing to the island in recent decades and reduced the pack's genetic diversity. With no new wolves, the animals inbred and developed genetic deformities that doomed their survival, spurring the National Park Service's dramatic wolf reintroduction effort aimed at maintaining some natural limit on the island's moose herd.

ADVERTISEMENT

Of the 19 wolves transported to Isle Royale between 2018 and 2019, researchers observed only two still alive during winter 2023; the rest are their descendants. That’s not surprising, researchers said, because most wild wolves do not live beyond 4.5 years old. All of the 19 translocated wolves would be older than 6 by now because they were at least 2 years old when they were brought to Isle Royale, so it would be surprising if a large number were still alive.

“The Park Service goal was 28 to 31 wolves on the island, so we’ve reached that,’’ Hoy said. “The only reason it might be necessary to bring more new wolves to the island at some point is inbreeding. Most of the wolves out there now are descendants of just two wolves from Michipicoten Island, so there may be some inbreeding issues that arise from that in the future.”

Meanwhile the number of young moose seen this winter, just 1.7 % of the overall moose population, was far below the normal and helps explain why the population is crashing. Spruce budworm insects are killing balsam fir — a key moose food — and blood-sucking winter ticks are stressing moose to the point they can’t survive winter.

Of the 10 GPS-collared moose that died over the past year, 70% starved, 20% were killed by wolves and 10% died from unknown causes. That starvation rate is far higher than past years when an average of just 5% of dead moose studied had perished from lack of food. Researchers said moose were so desperate for food they were trying to strip the thin bark off aspen trees, which is highly unusual.

At 45 miles long, Isle Royale is the largest island on Lake Superior, sitting about 14 miles off Minnesota's North Shore from Grand Portage. The island is a national park and mostly designated wilderness with few human visitors in summer and none in winter. There are no other major predators on the island, no human hunting is allowed and moose are the only large prey species, making it a unique wild laboratory for the ongoing study.

Moose first came to the island around 1900, peaking at 2,445 in 1995 and hitting bottom at just 385 in 2007. Wolves are relatively new to the island, having crossed the ice from the North Shore in 1949.

The island’s rebounded wolf population is doing a number on the island’s beaver population, which is down about 50% from before wolves were reintroduced in 2018. Beavers are an important summer food for wolves when moose are harder to catch.

ADVERTISEMENT