ROCHESTER, Minn. — Over the beeps and clicking of her dialysis machine, LaQuayia Goldring shared how her life has been affected by waiting six years for a kidney transplant.

“I’m in the category of a waiting and ailing patient. I’m trying desperately to avoid being a dying patient,” Goldring said at a May congressional hearing about inefficiencies in the organ transplant pipeline. “It seems like I’ve been let down by the system.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Goldring, a 31-year-old Kentucky resident, is one of 33,000 Black patients waiting for an organ transplant. In Minnesota, 352 Black patients sit on the list, 13% of the state’s waitlist. That’s nearly double their representation in the population.

Black patients are three times as likely as white patients to have kidney failure, yet these patients are less likely to be identified as transplant recipients. Inequities across racial groups permeate the health care system, contributing to higher numbers of people of color suffering from diseases that often lead to an organ transplant. Researchers are still measuring how many people die before even being listed.

A more diverse donor pool helps more waiting patients get the organs they need to survive. Specifically in the field of organ transplants, patient activists say organ procurement organizations (OPOs) may be the key to improving trust and donation rates among people of color.

These taxpayer-funded organizations are tasked with educating communities about donation and reaching populations that are typically underserved in health care. The federally designated OPOs also coordinate the transfer of organs from the deceased to transplant recipients. Right now, they’re falling short, missing up to , according to one government report.

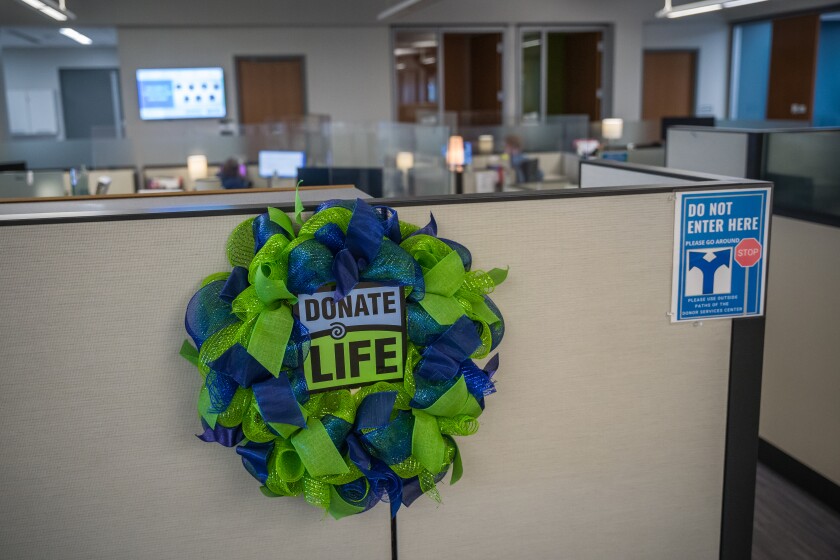

Minnesota’s OPO, LifeSource, is trying to improve diversity within and outside of its organization, while also confronting and a . Leaders who have worked in the field for decades say that as these organizations face new scrutiny, it may be the ideal opportunity to finally confront longstanding racial disparities.

Building trust

When someone dies with organs that are fit for donation, the OPO sends a representative to discuss the possibility of donation with the family. It's a delicate conversation, and needs to happen within a tight timeframe after the patient is declared dead.

"My team could sit on the phone with them for an hour, if that's what they needed. If emotionally they needed to process and tell stories to them about their loved one," said Laura Svoboda, who leads the family support team at LifeSource. The team transitioned to connecting with families over the phone during the pandemic, but have since returned to visiting hospitals in person.

ADVERTISEMENT

MORE: Read Organ Failure, parts 1 and 2

Bridging that gap can be harder if there are racial differences, says Laura Siminoff, dean of the College of Public Health at Temple University and researcher who has studied the transplant field and health care inequities for more than two decades.

“It is a more complicated process to talk with Black families about the opportunity for donation. Why? Because they hold a deep, deep distrust of the health system. Why? Because they’ve been discriminated against and their experiences within the health system are not great,” said Siminoff.

It’s a gap that the LifeSource team has observed. Svoboda said there is a greater suspicion among people of color that medical staff tried everything they could to save their loved one.

“We do, at times, see a larger number of communities of color wonder if their loved one was treated to the full level that they should have been,” said Svoboda.

ADVERTISEMENT

This is one of the persistent myths surrounding donation: that a medical team won’t work as hard to save a patient who is an organ donor. Mayo Clinic even set up a that addressed this concern and several other common misconceptions about donation.

"When you go to the hospital for treatment, doctors focus on saving your life — not somebody else's," reads the page.

LifeSource has long sought to address this distrust. In 2003, the OPO started a campaign to partner with Minneapolis community health clinics “to increase knowledge and support for donation in the African American community,” said LifeSource’s CEO Susan Gunderson. In order to better reach African American families in the Twin Cities, LifeSource also launched its Barbershop Conversations program in 2008, a collaborative of local barbers in the area who would convey information about donation to clients. In 2016, it started the "Talk Donation" campaign to increase donation in the American Indian community.

The Minnesota OPO ranked 34th out of 52 such organizations for its ability to convert African American organ donors, according to an analysis from University of Miami and Emory researchers. The analysis examined the 2010 to 2018 timeframe.

'Every time someone dies the phone rings'

Procurement organizations such as LifeSource have made a greater effort to bring community leaders in to educate staff on cultural empathy over the last decade, and especially the last two years. But often, the staff who work closely with families are too busy to attend.

Sheryl Raygor used to work at LifeSource in a job where she’d connect with families of the deceased to see if they may consent to tissue donation. Raygor, a woman of color herself, appreciated the organization’s efforts to bring speakers in to discuss how to communicate with families of different backgrounds.

ADVERTISEMENT

However, she worked on such a chronically understaffed team that employees couldn’t sit through these speakers.

“I think (LifeSource was) trying to do their best. It's just that information wasn't always absorbed by my team, because if you couldn't make the meeting because you were on the phone, you didn’t get that information,” said Raygor. “More required competency of cultural awareness, those types of things would have been a lot more beneficial to the department.”

LifeSource at a glance

LifeSource is a nonprofit organ procurement organization founded in 1989 and headquartered in Minneapolis.

LifeSource is under contract with the federal government to facilitate transplants across its 226,487-square-mile service area, serving 7.5 million people in Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota and western Wisconsin.

Since its inception, LifeSource said it has facilitated 17,000 organ transplants and reached 1 million tissue and corneal transplant recipients.

ADVERTISEMENT

Raygor left the company in 2018 because she did not feel it was a supportive environment for people of color, due to comments a coworker made about the Black Lives Matter movement and because of the treatment of her colleagues who were people of color.

LifeSource’s CEO said the company is focused on improvement in its racial equity initiatives and internal staff recruitment.

“We work to create and maintain an environment which is supportive of people of color and are focused on expanding diversity of our workforce. I am proud that in recent years we have increased the diversity of our team,” wrote Gunderson.

Brianna Doby has reviewed hundreds of calls that tissue donation coordinators made to families. In her work advising OPOs, she's used her analysis of the calls to improve compassionate approach and, ultimately, donation rate. She was also a contractor for LifeSource from 2013 to 2015.

She’s found that while organizations may have an interest in providing education for employees, they often don’t allow staff who communicate directly with families to attend those important events, because they’re working a call center every hour of the day.

"When I met people working in communication centers, I found that they were understaffed, underpaid,” said Doby. “You work in a place where every time someone dies the phone rings. That is a truly extraordinary thing.”

Rejecting the 'cookie cutter' mold

It’s a necessary but difficult task to implement effective racial diversity initiatives in a system where there is so much disparity and mistrust, said Janice Whaley, CEO of Donor Network West in California, the first Black female to fill such a role. The system hasn’t historically provided successful blueprints for empowering people of color to donate, she said.

ADVERTISEMENT

“That cookie-cutter type approach doesn't work anymore. And a lot of OPOs struggle with making the transition, or even how to make this transition,” Whaley said.

Researchers and OPO leaders themselves have identified the delicate balance these organizations need to strike. Staff must encourage donation but not push families, seek to gain a diverse donor pool but not exploit the loved ones of deceased people of color, and incentivize workers to continue performing well without making a numbers game out of it.

Whaley found sustainable ways of increasing her organization’s success with communities of color shortly after taking on the role of CEO. Since 2018, her OPO has increased donation rates in the Black community by 70%, with Pacific Islanders by 56% and within the Asian population by 64%.

“At the end of the day if we don't increase the number of people of color donating, we're never going to eliminate the waitlist,” said Whaley. She added that while race matching is not required for organ donors and recipients, patients of similar backgrounds may be more likely to successfully match.

One of the keys to her organization’s success was having the right staff member respond to the hospital to assist a grieving family. She encouraged her family support teams to consider who on the team could best interact with a specific family instead of simply sending out the next available staffer. Whaley engaged with a group of volunteer “ambassadors" to help connect with families of different backgrounds that the team may not be able to reach.

“There has to be cultural humility, and there also has to be our ability to really hone in and understand the needs and the diversity of our community and tap into non-traditional ways of getting people to start the conversation,” Whaley said.

At LifeSource, leaders from different backgrounds are seeking to encourage donation within their communities. Dr. Thomas Wyatt is a Hennepin Healthcare emergency room physician and an advocate for health education in the American Indian community. He’s worked with members of this community to identify barriers to donation.

For American Indians, Wyatt said there is discomfort with receiving personal gifts from strangers. Such cultural facets must be understood before educational efforts can be effective, he said.

“The way I kind of look at it is it's very similar to health care. It's really important (if) you're taking care of a very diverse community for most people that deliver the care, providing care, to kind of mirror that population,” said Wyatt.

That’s an area where LifeSource is looking to improve.

Of the LifeSource team, 11% are people of color, as are 23% of the 13-person executive team, according to Gunderson. She has led the OPO for 32 years and will retire next year.

The organization is striving to “ensure that our workforce looks like and represents the communities that we serve in every way from all levels from the board to the clinical advisory boards, to our frontline team members to our internal leaders,” Gunderson said.

The team of family support coordinators, which is often the first point of contact families have with the OPO, may be the most important place to start. Two LifeSource members of its 10-person support team are people of color, and one speaks a language other than English. In many cases where a donor family does not speak English, translators are employed.

“I would love to have a more diverse staff and (we) are continuing to work on that,” said Svoboda, who leads that support team.

OPO leaders say it’s been sometimes difficult to recruit a workforce that reflects its population. Yet, it is one of the most tested ways to improve donation. Research supports the efficacy of having an OPO worker of the same race approach a family, and one study indicates that translator use may lower donor authorization rates.

'A piece of the puzzle'

The largest shift in OPO regulations may provide an opportunity to have tough conversations around how the transplant system can reduce inequities. Whereas OPOs were previously judged by , their performance will now be evaluated against objective, federal death certificate data.

Congress has also held hearings and launched investigations into a select group of OPOs, with racial equity being a central part of their focus. LifeSource is one of 11 OPOs under .

It’s an overdue change in the eyes of many who have worked in the industry since organ procurement groups were established more than three decades ago.

“The system doesn’t know or believe that it’s being biased. That’s the largest problem and until the (congressional) hearings and things of that nature where their actions are pointed out to them, it’d never crossed their thought pattern that they were being covert. They were being, by design, biased,” said Jack Lynch, senior advisor for Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donation Network, an OPO in Illinois.

Lynch said the new metrics will “absolutely” hold OPOs to a greater sense of responsibility, and improve their outreach to diverse groups. “It’s a long time coming,” he said.

As OPOs have faced a reckoning over poor performance, some leaders have blamed lower donation rates among non-white people in their service area. They argued to regulators that because their organization served a diverse population, it should have race-adjusted rankings that would not penalize poor performance.

But these organizations may have had a role in damaging donation rates, according to research by Laura Siminoff. Her findings indicate that Black families are approached by OPO staff on fewer occasions than white families, and that Black families were not presented with as much information regarding the opportunity to donate organs.

Lawmakers say the issue must be addressed urgently, as the pandemic disproportionately sickens people of color.

“The COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating the need for organs now and creating an urgent health equity issue, as communities of color are disproportionately impacted by the failures of the current organ donation system and the effects of COVID-19,” said a signed by 12 members of Congress to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

It’s just another example of how health care and societal inequities are linked to the transplant system, a phenomenon Siminoff has consistently observed for decades.

“That's the tragedy of the American health system, particularly for minorities, and especially for the Black community,” said Siminoff. “OPOs aren’t going to solve that. But they do have a piece of the puzzle. And there are better ways to do it.”

How do I register to be a donor?

- You can register to be an organ donor with the national Donate Life registry or your local state registry. Both should be checked to confirm if you are a registered donor, and you can register in both.

- According to Donate Life America’s , “Any adult age 18 or older can register to be an organ, eye and tissue donor – regardless of age or medical history; 15-17 year olds can register their intent to be organ, eye and tissue donors in the National Donate Life Registry. However, until they are 18 years old, a parent or legal guardian makes the final donation decision.”

- For Minnesota residents, you can register here: .

- To register on the national registry, visit this link: . Contact customerservice@donatelife.net with any questions.