This is Part 1 of the Minnesota Vice series.

OVER ANDROS ISLAND, THE BAHAMAS — Vincent Tirado was descending to a landing in the Bahamas when the call came in: A chase is on, bring the chopper.

ADVERTISEMENT

Tirado, co-pilot in the dark-olive-drab UH-60 Black Hawk, quickly worked out his new flight direction and his helicopter thwack-thwacked its way back into the hot sky, heading due north.

It was just about 1 p.m. on April 23, 1983. A Saturday.

Tirado, a pilot for U.S. Customs, hunted for drugs and drug smugglers. Drug interdiction, it was called.

His helicopter was new to the Customs arsenal, on loan from the Army, part of President Ronald Reagan’s new South Florida drug task force.

Every day, Customs was sending up pilots like Tirado to patrol the sky off the east coast of Florida, north and south of Miami, scanning for suspicious airplanes.

Today, a fellow Customs aircraft was tailing a suspect plane just east of Florida, over The Bahamas — an archipelago nation of some 700 islands.

Tirado’s Black Hawk could cruise at about 175 mph, faster if needed, so it quickly closed the distance to the radioed-in coordinates.

ADVERTISEMENT

Tally ho. There they were.

Tirado could see the fast, twin-engine Customs pursuit plane following a smaller, single-engine, high-wing Cessna 210, glinting in the distance, its light skin striped with blue.

Its tail number was N6608C, or as a pilot would identify it over the radio using the phonetic alphabet: "6608 Charlie."

Tirado fell in behind them—close but not too close. The Customs pilots' job was to tail the Cessna, keep it under observation, see what it would do next.

The Cessna was heading north-northwest, in the general direction of Grand Bahama Island, flying steady and true. It was entirely possible its pilot wasn’t aware he was being tailed.

Tirado watched as the Cessna turned then, curving west toward Florida, visible on the horizon.

Interesting. Very interesting.

ADVERTISEMENT

The two Customs aircraft trailed behind the Cessna as it cruised in the sky about the Atlantic Ocean, toward the U.S. coast, about 150 miles away.

The miles melted away under the hot sun. The Cessna could potentially outrace Tirado’s Black Hawk, but if the pilot decided to run, it would be difficult to outrun the speedy and radar-equipped Customs plane.

Then again, sometimes smugglers in these small planes would try to evade authorities by shaking them off, flying so slow it would force faster pursuit aircraft to overfly them and circle back, opening chances to escape.

That’s where Tirado’s helicopter might come in handy — it could fly as slowly as needed.

As Florida grew larger in Tirado’s windshield, another Customs twin-engine aircraft came into view. This was pilot James McCawley.

McCawley had taken off from Florida and now joined the chase just off-shore, pulling in behind Tirado’s Black Hawk — a three-aircraft Customs air force strung out behind a small Cessna.

Landfall. Florida. The Cessna’s shadow cuts across the beaches of Boca Raton, just north of Miami.

ADVERTISEMENT

It was now 3 p.m. Tirado had been tailing the Cessna for nearly two hours, waiting, watching.

The Customs pilots knew this was a critical moment in the chase, the moment when the Cessna pilot — making landfall — might first break the law.

“The law requires that they stop at one of the first airports with Customs service, which means, basically, Miami, Fort Lauderdale — Key West if they’re coming from that direction,” McCawley said in later court testimony. “If they overfly those airports, they are already committing a violation of the law.”

This Cessna was now 15 miles inland and was well past those airports. This was not a normal flight path for a pilot, say, casually returning from a vacation in The Bahamas.

The Cessna’s wings flashed in the sun. It was turning again, a big sweeping right turn, almost a full circle. McCawley knew that move.

“It permits him to pretty well view the whole surrounding area to see if there are other aircraft in the area,” he said.

The pilot likely now knew the feds were tailing the Cessna.

ADVERTISEMENT

The pilot turned again, heading off-shore, flying uncertain, erratic almost, far above the breaking waves. The plane then turned back toward Florida then doubled back again toward the Bahamas.

“On the way there, it was flying through clouds, flying very slowly, making turns,” McCawley said.

All this added up to one conclusion.

The Cessna pilot was trying to flee.

TWO YEARS EARLIER - April 1981, Princeton, Minnesota - 2,500 miles away from Miami

Bob Manary really wanted to get this guy.

It was a cool spring day in Princeton, Minnesota, April 14, 1981. A Tuesday.

Earlier you could’ve seen your breath in the chilly air. It was a bit warmer now, but the wind still buffeted Manary’s car, a nondescript, unmarked sedan owned by his TV station, WCCO, based in Minneapolis, about 50 miles to the southeast.

ADVERTISEMENT

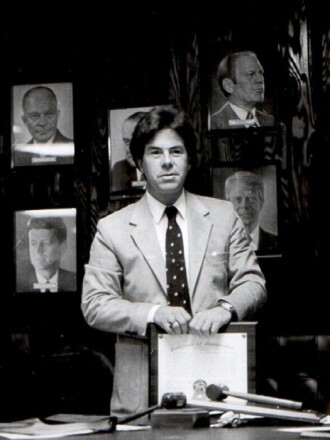

Manary, 41, was a photojournalist, a wielder of one of those big shoulder-mounted TV cameras. Dave “Nim” Nimmer, a WCCO reporter, was riding shotgun. They were following a mystery man by the name of Casey Ramirez, looking to interview him.

Ramirez was riding in the back seat of a 1957 Chevy driven by Airport Commission Chairman Dick Nelles, a local insurance agent.

Manary and Nimmer had just spotted Ramirez and were now tailing him. Manary, keeping pace with the Chevy, leaned forward for a closer look, curious, trying to see this mystery man, who didn’t look back.

This wasn’t going to be a long chase. This was Princeton, after all, a small town of 3,000 people on the Rum River, surrounded by dairies and farm fields.

There weren’t many places for them to go. Few streets. And Manary knew them all well.

****

Manary was Princeton born and raised. He was born in 1940, then joined the Navy after graduating high school, flying F-4 Phantom fighter-bombers in Vietnam and elsewhere before returning home to Princeton in 1962.

He started a local newspaper, grew it into an award-winning operation, then sold it to the competition. But journalism was in his blood.

Now he lived in Minneapolis, working as a TV news photographer for WCCO, a CBS affiliate, Channel 4 on your TV dial.

It suited him. WCCO had earned a reputation for its fearless news team.

“I was sent all over the world — all over the world,” Manary recalled in a recent interview. “Places that you were shot at many times, the Berlin Wall and things like that.”

Manary earned the nickname “Bullet Bob” in the newsroom because of how often he ended up in the middle of the action. He was a magnet for it.

Nimmer, an experienced reporter about the same age as Manary, had agreed to join his colleague on his drive back to his sleepy hometown to liven up an otherwise slow news day, to look for this guy named Ramirez. It sounded like it could make for a good story.

“‘CCO was, at the time — any story you could come up with, a good story — ‘go for it,’ and it could be any place in the world,” Manary said.

So of course, with Bullet Bob’s strange luck, he and Nim found themselves in a low-grade car chase in small-town Minnesota, chasing this mystery man.

****

The old Chevy stopped in front of Nelles’ office in downtown Princeton. From a distance they saw Ramirez and Nelles head inside.

Manary remembered then — the office used to be a restaurant. It had a backdoor into an alley. He dropped off Nimmer out front. Classic pincer movement. Nimmer went through the front door; Manary pulled around the corner into the alley.

His hunch was correct. There he was, Ramirez, the mystery man, apparently fleeing.

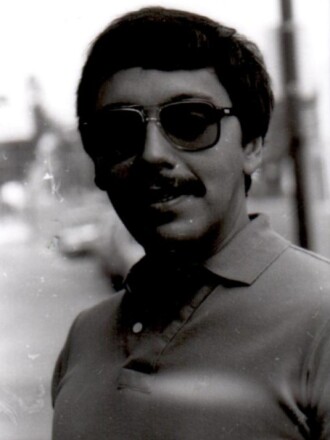

He was in his 30s, of medium height, Hispanic features, straight dark hair, well dressed — a blazer over a polo shirt unbuttoned at the neck.

Manary pulled his unmarked car alongside Ramirez, all casual, and offered him a ride.

He jumped in, anxious, hassled, grateful against the cold. Manary introduced himself as a local, name only.

Ramirez lit up, flashing a big smile. “Oh, I know you,” he said, with an accent that sounded like New York City.

No you don’t, Manary thought.

Ramirez asked for a quick drive into the country, to escape some out-of-town TV news crew seeking an interview.

Manary confessed the truth: He was from WCCO, actually, that TV news crew. So how about that interview?

Ramirez reluctantly agreed to an on-camera interview, but on one condition: Don’t show my face.

Manary agreed.

He didn’t know much about Ramirez, really. He knew he was from out of town, seemed to already be good friends with Mayor Richard Anderson and some other big shots, and he had recently spent thousands of dollars on Princeton town projects.

He also had a certain way about him.

“Casey — you’ve got to understand — he was very charismatic,” Manary recently recalled. “If he was talking to you here, he could win you right over.”

Ramirez had asked for the interview to take place in the office of Jerry Davis, the manager of the Princeton Co-op Credit Union, downtown.

There, the WCCO duo got set up. Ramirez settled into a chair. It would be his first time on camera like this. It wouldn’t be the last.

****

Manary had read about Ramirez's big spending in Princeton. Everyone in town had. It had been front-page local news.

In December 1980, the Princeton Union-Eagle reported about Ramirez’s plans to buy some airport land for about $42,500. It wasn't clear what he wanted to do with it, exactly.

By March, Ramirez was generating bigger headlines — spending big money, making big promises.

Ramirez was "a man in his early 30s, and holder of at least ...$1 million through air charter service and a computer corporation," wrote Princeton Union-Eagle reporter Joel Stottrup, in news coverage about the airport. Ramirez claimed to have "offices in Miami, Phoenix, Hawaii, London and elsewhere."

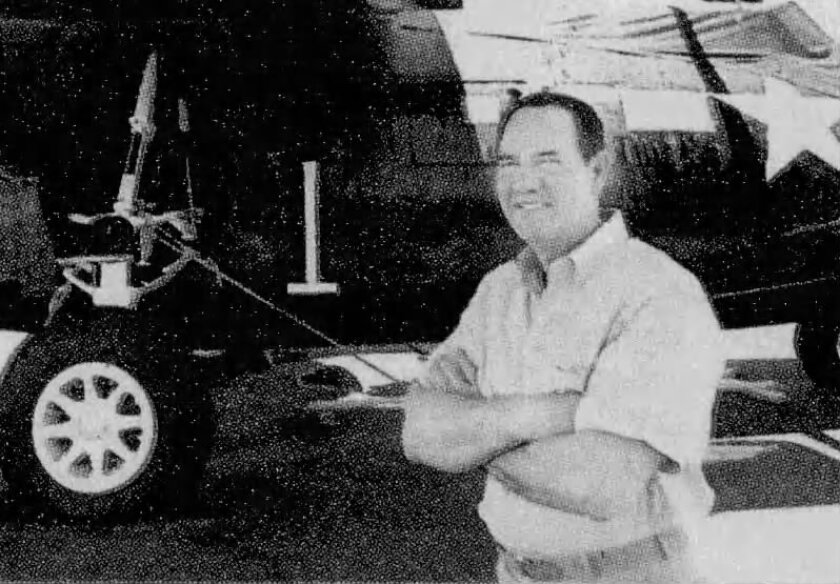

Ramirez was named the town’s newest airport commissioner. After all, he seemed to be very interested in bailing out the town's airport, which despite town leaders' hopes of building it up, had become something of a municipal money pit

"It was nothing — just kind of a grass field," Manary remembered in a recent interview. “Casey [said], 'I’ll do Princeton a great favor and build you a great big nice runway.'"

On March 2, 1981, Ramirez took his fellow airport commissioners and dozens of other Princetonians out to the The Farm Supper Club on Highway 95 for an official "meeting" featuring prime rib, champagne and entertainment.

“About 100 people that ‘he wanted to get to know better,’” wrote Stottrup, who was there to cover the meeting.

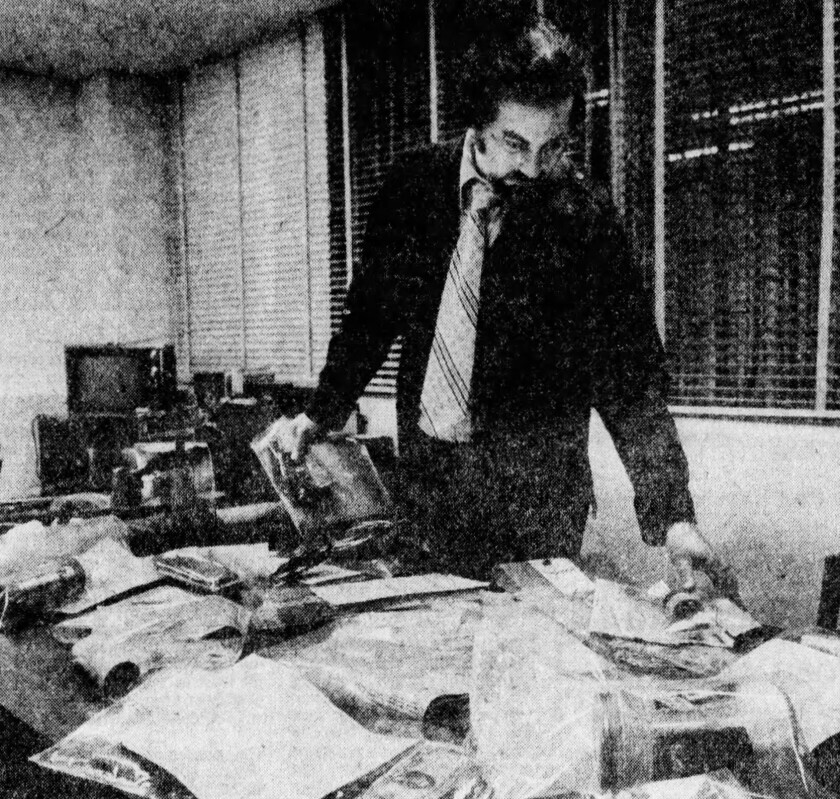

The reporter snapped a photo of Ramirez that was published in the paper. A mustachioed Ramirez was sporting a jacket and tie, dark glasses, laughing at a banquet table, holding court.

He was flanked by big-shot Minneapolis criminal defense lawyer Ron Meshbesher, his wife Patti and Princeton Mayor Richard Anderson.

"Ramirez added a flavor to the commission meeting that some may not have been accustomed to,” wrote Stottrup. “The flavor was an offer of quick solutions in the form of money to problems that the commission has been struggling to solve for months because of lack of money."

The airport wasn’t the only thing Ramirez was bankrolling. In the weeks after The Farm dinner, Ramirez agreed to back a $400,000 interest-free loan to fund construction of an municipal ice arena and offered $100,000 in fancy newfangled computers for City Hall.

To Manary, it all sounded suspicious. Where was all this money coming from? Why was he putting it into the airport, City Hall and an ice arena?

He worried Princeton was getting played by a smooth operator.

“If you didn't know, you'd like the guy. He's, like, doing all these nice things for people and that sort of thing,” Manary recalled later. “But I'd been around the horn for a few times, and yeah — by time he got there, I knew what to watch for.”

Manary was protective of Princeton. It wasn’t just his hometown — it was a special place.

“We always felt that growing up in Princeton was the best place in the world. Looking back on it today, I would not want anything changed,” he said in a 1992 written recollection. “The world was not so complicated. We didn’t have to worry about crime and drugs like today’s children must do every day. We knew some of that was in the far off city but [it] couldn’t affect us.”

But just about the time Ramirez popped up in Princeton, the town felt vulnerable to Manary.

City Hall was having a hard time with its finances, and not just because of the airport. A newly completed highway bypass had sucked business out of downtown, just when the national economy was stuttering, giving Princeton a one-two economic gut punch.

****

Manary looked through his camera lens at Ramirez, and zoomed in—a tight shot. Ramirez, knowing his face was obscured, looked right into the camera.

Nimmer asked the big questions: Why Princeton? Who are you? What’s with all the sudden generosity?

Ramirez said he had first come to Princeton because it was the home of the Richard and Lois Bredemus family.

Their daughter, also nicknamed Casey, had saved his life while Ramirez was in the Navy, he said. He had first visited to pay her back.

As to all his money, he claimed he had won a patent on an aircraft wing part while playing poker, then was able to lease it for $5 million, which he invested in other business ventures.

Ramirez bobbed his head sideways, his eyes shifting behind his large dark glasses. A flash of a smile.

“I come to Princeton here, they didn’t care what my name was, who I was — they were basically interested in my integrity … It was very touching,” he said from the shadows, that touch of an NYC accent.

“We don’t have the problems out here of a lot of other communities, a lot of other countries,” he said. “We’re very fortunate....So I consider myself fortunate to be part of this community.”

The interview made Manary even more suspicious. And he wasn't alone.

THAT SAME MONTH — DEA Resident Office, Minneapolis

Michele Leonhart was back home but she felt out of place.

There she was, 25, sitting alone at a desk in the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency's Minneapolis Resident Office, its local field office. Apparently this was to be her new desk.

This was Leonhart’s first day at her first duty post as a DEA special agent.

"I was in my suit, and had my little briefcase," she recently recalled.

She had arrived at the office early, only to wait until a secretary arrived and let her in—nobody else in the office.

So where was everyone?

She had grown up in and graduated high school in White Bear Lake, Minnesota, then got her associate degree in criminal justice from Lakewood Community College, before going up north to Bemidji State University.

She had always wanted to be a police officer. She applied to the police departments in the 20 biggest U.S. cities, and all said no except one: Baltimore. Now those had been some mean streets — very different from back home in Minnesota.

In Baltimore, she learned fast, made plenty of arrests, impressed a lot of people. She decided she wanted to catch big fish with a national agency, so she attended the DEA academy, and graduated at the top of her class.

She had earned the right to pick her first duty post.

It had to be Miami, right? South Florida? That’s what everyone thought was the natural choice.

****

South Florida in early 1981 was the hottest of spots for an ambitious new DEA agent. It was the front line in an escalating battle against international drug smugglers, who seemed to have endless resources, a predilection for violence and a bottomless supply.

Cocaine was coursing through America’s blood in 1981, much of it funneled from South America through South Florida, America’s toe into the Caribbean.

“In the drug world, everything revolved around Florida back then,” Leonhart recalled in a recent interview.

The smugglers were getting bolder by the day. Gone were the days when human "mules" would try to bring in small amount of cocaine on (or in) their person. The operations to meet the seemingly inexhaustible demand.

One had even opened a transshipment point on a tiny island in The Bahamas — white sand with a 3,300-foot crushed-coral airstrip, less than a two-hour flight from Florida.

Pilots in small planes were flying in bales of pot and kilos of cocaine. Some would drop the drugs to speedboats to make delivery runs into secret coves on the coast.

Others flew straight into the Sunshine State, dropping off loads of drugs at airstrips guarded by nobody but gators in the nearby swamps.

The authorities were catching more and more of the deliveries but were also sure they were missing a lot of what was coming in.

Cocaine seizures in the Miami area totaled 850 pounds in 1979. In 1980, authorities .

In January 1981, the Miami News depicting that month's drug seizures in Dade County, which encompassed Miami.

With the rising tide of drugs Where there was drugs, there was money, and where there was money, there was crime.

The DEA was doing what it could. It was an eight-year-old agency in 1981, at the forefront of President Richard Nixon’s War on Drugs. But it had languished in the ‘70s as America's attitude toward drugs moved toward acceptance, including decriminalization of cannabis.

Cocaine seemed like the next big thing. For users, it provided a short, euphoric high. Many considered it just as harmless as pot.

For sellers, cocaine was easier to transport, and pound for pound, significantly more coveted, more lucrative.

Yet cocaine remained expensive to get. It was difficult to source and hard to make.

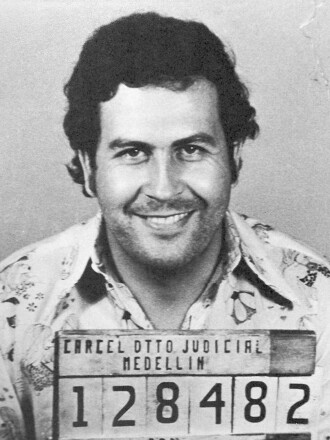

But the growing Medellin Cartel in Colombia — led by a mustachioed up-and-comer named — had refined ways to make cocaine in bulk.

Now the cartel's challenge was to find ways to get its production past law enforcement into the United States, where there was endless demand—tens of millions of Americans eager for the next big high.

Every step of the cocaine production and delivery process generated a spider web of crime and misery. The supply lines were secured by violence, human suffering and corruption: lot of people, by force or by choice, looking the other way.

Reagan, the newly elected Republican U.S. president, seemed eager to bring the full force of the government against the wave of cocaine then arriving in South Florida. The DEA would be on the forefront of this battle. All hands on deck.

****

Leonhart, the newly minted DEA agent, had earned the right to pick her first post.

So assignment: Miami it was, right?

She decided to go a different way.

“I picked Minneapolis,” she said. “It’s the only reason I ended up in Minneapolis. I figured [if] I was going to clean up the streets, I wanted to clean up in Minnesota — I wanted to go back there and do what I could.”

Now her first case seemed to be figuring out why the Minneapolis DEA office was empty.

She didn’t need to sit long. Her new boss, Resident Agent in Charge Jim Braseth, walked in. Everyone was at a picnic, he said — she should go home and change.

At the picnic, Braseth wasted no time telling Leonhart about his plans for her first assignment. He wanted her to go undercover to investigate some mystery man up the road in the small town of Princeton.

“This 'mysterious benefactor,' as they called him,” Leonhart said.

WCCO TV had just done a news report about him. He didn't seem to have any job or clear source of money, yet was ostentatiously wealthy. He went by the name Casey Ramirez.

But before he told her all that, Braseth had a question for Leonhart.

He knew how to set the hook.

“Hey, how’d you like to meet a millionaire?”

Notes: This article is based on interviews for this series with Leonhart, Manary, Nimmer and Don Shelby, as well as Ramirez trial transcripts and associated papers housed in the collections of the National Archives branch in Chicago, a 1992 recollection column by Manary, microfilmed copies of Princeton newspapers housed in the collections of the in St. Paul, Princeton Union-Eagle photos archived by the in Princeton, for 1975-1980 and 1980-1985, a about the drug war in South Florida, clips of WCCO news broadcasts The 1995 PBS Frontline series and the 2020 book “ by Nicholas Griffin. Ramirez never responded to multiple interview requests. Stottrup declined to be interviewed. Deceased include Braseth (2000), Meshbesher (2018) and Nelles (2020).