Reporter Trisha Taurinskas unpacks the North Dakota mystery in this multiple-part series.

Read more here: https://www.inforum.com/news/the-vault/police-file-reveals-flawed-investigation-into-1996-missing-persons-case-of-north-dakota-mother-and-son

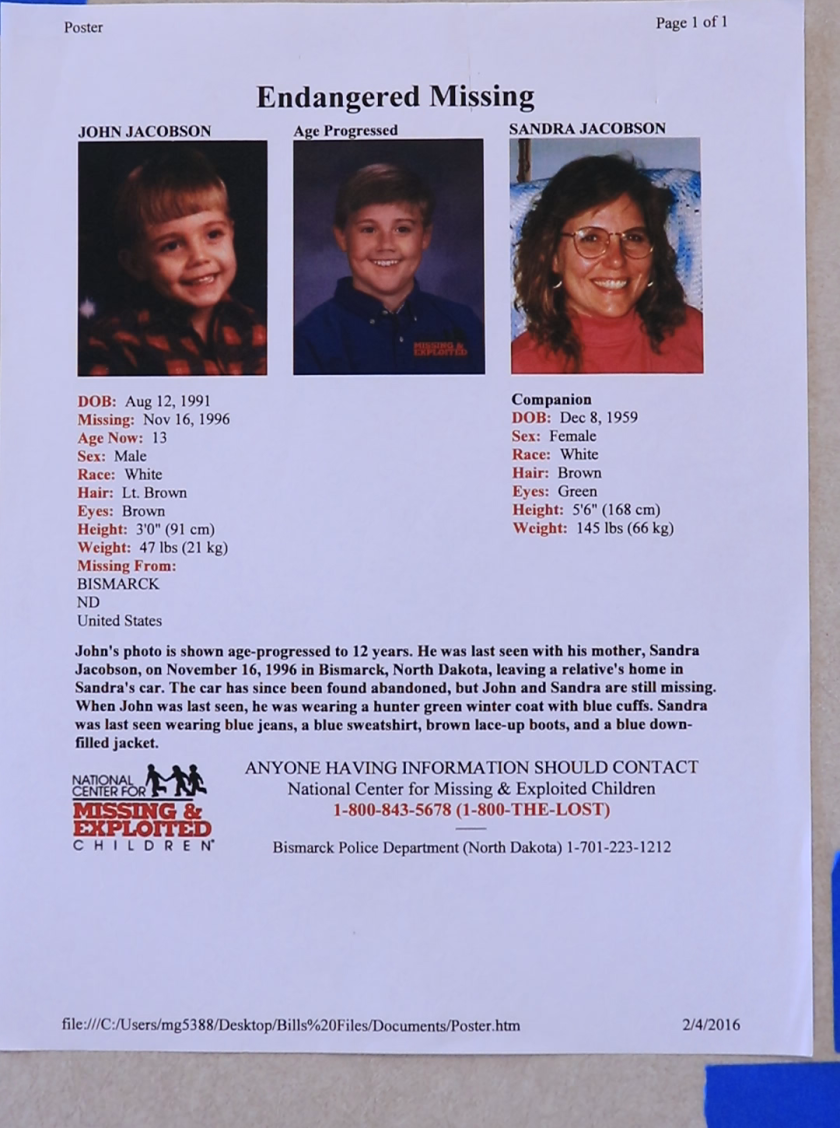

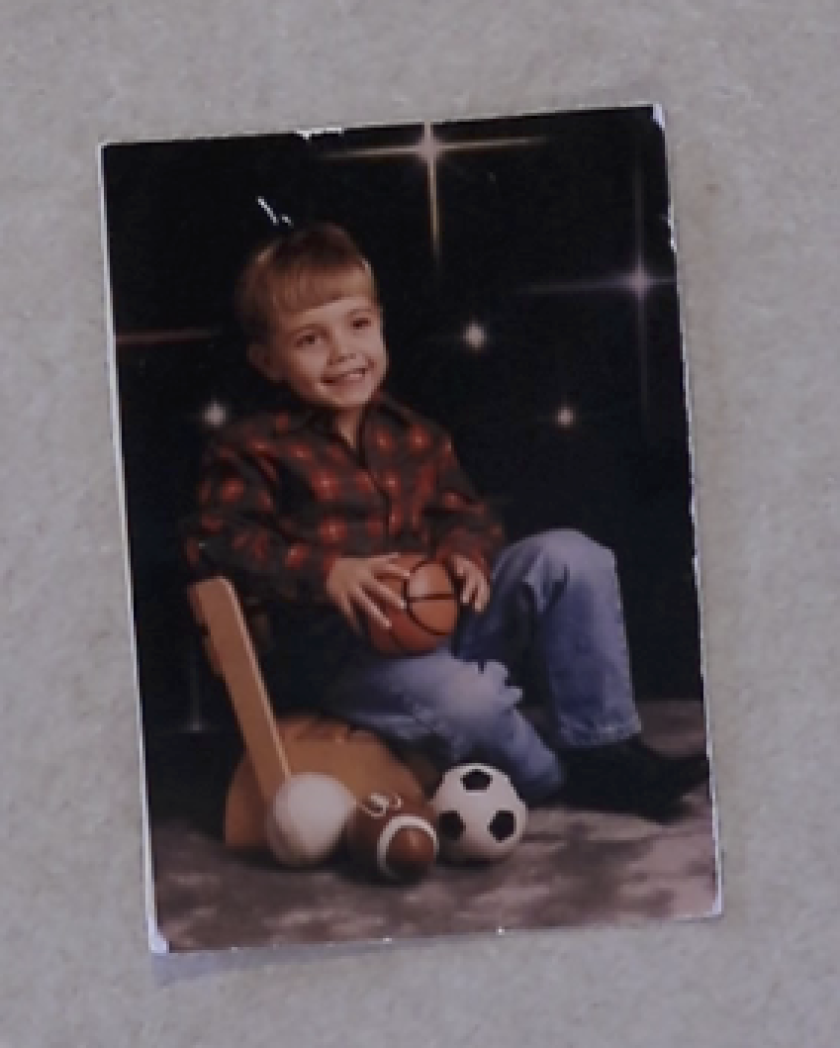

Editor's note: This is the first in a multiple-part series examining the investigation into the 1996 disappearance of 35-year-old Sandra Jacobson and her son, 5-year-old John Jacobson. To read part 2, go here.

BISMARCK ŌĆö Sergeant William ConnorŌĆÖs phone rang on the afternoon of June 2, 2004. On the other end was a representative from the Missing and Exploited ChildrenŌĆÖs Center, who believed they may have had ŌĆ£a hitŌĆØ ŌĆō a clue ŌĆō on a 1996 missing persons case from his jurisdiction.

ADVERTISEMENT

It concerned the case of Sandra Jacobson, who on the evening of Nov. 16, 1996, left her parentsŌĆÖ Bismarck home, along with her 5-year-old son, to get gas. Her Honda Civic, found the following morning near the Missouri River in BismarckŌĆÖs Centennial Park, contained her purse, which included, among other items, a checkbook logging a Nov. 16 transaction to a local gas station.

In the phone call, the Center alerted Connor that there was a person named Sandra Jacobson living in Mandan, a town located just across the river from Bismarck.

While the hit turned out to be a dead end, it began a years-long quest by Connor to re-examine the investigation.

The police file from this case, recently obtained by Forum News Service, reveals what Connor found: a missing persons investigation that left key questions unanswered, vital evidence unaccounted for and potential suspects cut loose.

While the file does not indicate a guilty party, it does pose some hard questions: Did the Bismarck Police DepartmentŌĆÖs initial investigation into the disappearance of Sandra and John Jacobson look at all possible angles? Or did it miss asking some crucial questions?

Revisiting the case

On the morning of Sunday, Nov. 17, 1996, Bismarck Police officers discovered a gray 1990 Honda Civic parked alongside the Missouri River in Centennial Park ŌĆö its driverŌĆÖs door cranked wide open.

ADVERTISEMENT

With high winds and temperatures well below freezing, an open door was a sign to law enforcement officers that something wasnŌĆÖt quite right.

They were correct.

Officers discovered keys in the ignition and a purse sitting on the passengerŌĆÖs seat, but their efforts to search the area for the driver came up short. A light dusting of snow that fell overnight erased any hope for footprints leading them to the truth.

The discovery of the car was the start of a missing persons case that would haunt the Bismarck Police Department for decades.

A reactionary focus on the river

Detective Tim Turnbull walked in the doors of the Bismarck Police Department on the morning of Monday, Nov. 18 and was greeted with a missing persons report filed over the weekend.

In the report, Turnbull learned that a mother and son from Center, North Dakota, had been reported missing by Bernice Grensteiner, Sandra JacobsonŌĆÖs mother. Grensteiner told the Bismarck Police Department that her daughter was having mental health issues when she left the evening of Nov. 16 to get some gas. She hadnŌĆÖt heard from them since.

There was something else in the report that stood out to Turnbull. A woman who identified herself as Sandra Jacobson had called the Bismarck Police Department hours before she went missing, claiming a loved one was in danger at the hands of a satanic cult.

ADVERTISEMENT

That set off a train of thought for Turnbull, who assumed a distraught and mentally ill woman had snapped, leading her down a dark path that ended in the frigid waters of the Missouri River, her 5-year-old boy in tow.

Right away that morning, he called up the Burleigh County SheriffŌĆÖs Office and asked them to start searching the river. The initial investigation into their disappearance, led by Turnbull, had begun.

A missing alibi gone unnoticed

Later that day, Turnbull met with Sandra JacobsonŌĆÖs husband, Alan Jacobson, who arrived at the police station fresh off a flight from a business trip in Missouri. He had been told the day before that his wife and son had been reported missing.

What Turnbull didnŌĆÖt know when Alan Jacobson walked into his office on Nov. 18 was that things had been rocky for the couple. At the time of the disappearance, Sandra Jacobson and her husband were in the midst of a separation. Their 5-year-old son, John, was living with his mother in Center, located 40 miles outside of Bismarck.

In multiple interviews conducted by investigators throughout the years, her parents, relatives and close friends said Sandra Jacobson believed she was days away from a divorce ŌĆö a process she claimed was being handled by her soon-to-be ex-husband.

Subsequent investigations would reveal no evidence of the initiation of a divorce process. Alan Jacobson never mentioned the divorce to Turnbull, either.

Instead, Turnbull listened as Alan Jacobson told him he and his wife were separated. Although they lived apart, he told Turnbull that he had recently been having trouble with his wife, fueled by what he referred to as her conspiracy theories that he was having affairs. According to the police file, he claimed those allegations were ŌĆ£totally off the wall.ŌĆØ

Alan Jacobson went on to paint the picture of an unstable woman with periodic religious obsessions, at one point telling the detective that his wife appeared ŌĆ£glossy-eyedŌĆØ during a visit to his home the week before her disappearance.

ADVERTISEMENT

ŌĆ£He stated she got real excited and was shaking and tried to get up and leave and he grabbed her and sat her down and stayed with her until she calmed down,ŌĆØ Turnbull wrote in his follow-up report.

Alan Jacobson told the detective his wife called him at around 6:15 a.m. the morning of Nov. 16 ŌĆö the last day she was heard from ŌĆö and told him to pray for their son. Specifically, he said she requested he recite the LordŌĆÖs Prayer.

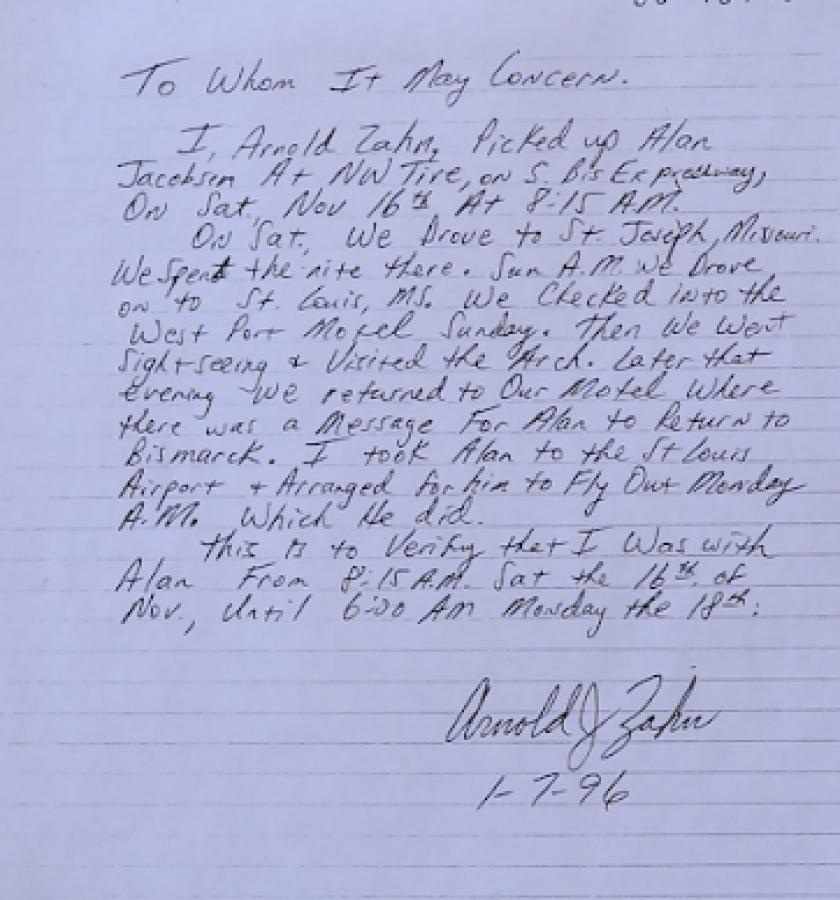

Having just returned from a trip to Missouri, Turnbull inquired as to the dates he had been traveling. According to Alan Jacobson, he left the morning of Nov. 16 and returned that day, Nov. 18, just prior to arriving at the police station.

That was, somehow, good enough for Turnbull. It wasnŌĆÖt, however, good enough for his superiors.

On Dec. 30 ŌĆö more than one month after Sandra and John Jacobson went missing ŌĆö Turnbull met with Lt. Myron Heinle and Sgt. Nick Sevart regarding the case. Concerned that Alan JacobsonŌĆÖs alibi had not been properly vetted, they came up with a new plan.

That same day, Turnbull reached out to Alan Jacobson to go over the details of his November work trip. Documents in the police file show that Alan Jacobson claimed he left North Dakota on Saturday, Nov. 16 at around 8 a.m. and rode with six other people in a van to Missouri.

ŌĆ£He stated he got to the hotel room on that Sunday, 11-17-96,ŌĆØ Turnbull wrote in the follow-up report.

ADVERTISEMENT

Turnbull followed through with calling the Westport Hotel, where he confirmed with the manager that Alan Jacobson had stayed for only a single night: Nov. 17, 1996.

While Turnbull requested the manager fax a copy of the records to the Bismarck Police Department, he was informed it was against company policy to do so without a subpoena.

According to the police file, Turnbull did not obtain information as to where Alan Jacobson stayed the night of Nov. 16, the evening Sandra and John Jacobson went missing.

Yet Turnbull indicated in his follow-up report that Alan JacobsonŌĆÖs alibi checked out.

On Jan. 7, Turnbull received a handwritten letter from Alan JacobsonŌĆÖs coworker, who wrote that the two drove together to St. Joseph, Missouri on Nov. 16, where they stayed the night. The coworker wrote they then traveled to St. Louis on Sunday, where they spent the evening sightseeing before returning to the hotel.

Turnbull did not follow up with the coworker who wrote the letter, according to the report. Questions as to where Alan Jacobson stayed the evening of Nov. 16, 1996 went unquestioned ŌĆö and remain unanswered.

Processing the vehicle

ADVERTISEMENT

On the day it was discovered, the 1990 Honda Civic was taken to the Bismarck Police Department for documentation. Yet with no foul play suspected, the vehicle was not fingerprinted.

It was a move that frustrated those close to Sandra Jacobson, who met with the Bismarck police on Dec. 27 seeking answers.

ŌĆ£I told them that even if we found a set of prints that did not belong to Alan or Sandy, we would need a suspect to match them to and at this time there are no suspects,ŌĆØ Sevart wrote in the follow-up report.

That was difficult for Sandra JacobsonŌĆÖs loved ones to handle. They were aware that a close family member who received a phone call the day she went missing told investigators on Nov. 26 that they suspected there was a third party in the vehicle.

There was something else that didnŌĆÖt sit well with them. In the days after the disappearance, Alan Jacobson entered Sandra JacobsonŌĆÖs home and allegedly took a number of items. They wondered why law enforcement had allowed him to do that.

The answer? They were married. It was his property, too.

The same reasoning was used when Sandra JacobsonŌĆÖs purse was released to Alan Jacobson on Nov. 27 ŌĆö and again on Dec. 23, when he drove the 1990 Honda Civic off the Bismarck Police Department lot.

Closing out the investigation

While interviews with those close to Sandra Jacobson continued to be conducted in the months following her disappearance, investigators focused heavily on searching the Missouri River. The North Dakota National Guard was called in multiple times to search from the skies, while dive teams did their best to navigate the frigid waters.

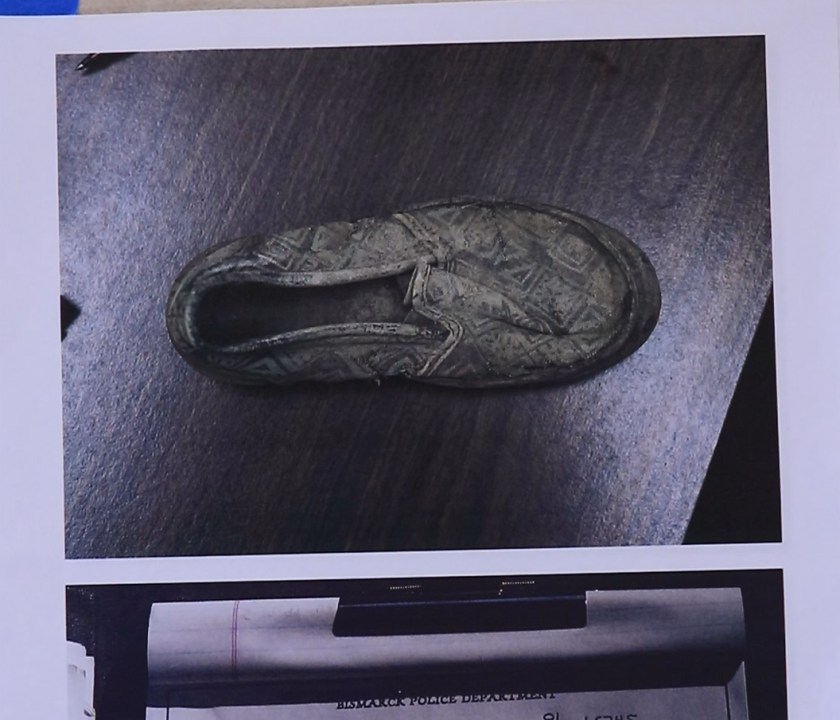

A childŌĆÖs shoe found near the river in Centennial Park on May 20,1997 gave investigators hope that it could belong to John Jacobson. While Alan Jacobson told Turnbull at the time that he believed the shoe could belong to his son, John JacobsonŌĆÖs older brother and grandmother adamantly said the shoe wasnŌĆÖt his ŌĆö it was far too large.

In the spring of 1997, Turnbull made efforts through local media to alert boaters to be on the lookout for anything that could point them to the discovery of Sandra and John Jacobson. Ultimately, nothing turned up.

Throughout the years, investigators received phone calls from those claiming to have seen the mother and son. All leads were thoroughly investigated ŌĆö in the end, they amounted to cases of mistaken identity.

On Feb. 23, 1999, Turnbull declared the case inactive.

ŌĆ£There are no further leads in this case,ŌĆØ he wrote in the report, ŌĆ£The case will be filed until something further comes up.ŌĆØ

In part 2 of this series , learn what Connor discovered as he attempted to go back in time to uncover unanswered questions that could shed light on what happened to Sandra and John Jacobson.