GILBERT, Minn. -- Michelle Little always wanted her mother to tell this story.

“I even bought her a journal,” Little said of her late mother, Judith Little. “She didn’t use it.”

ADVERTISEMENT

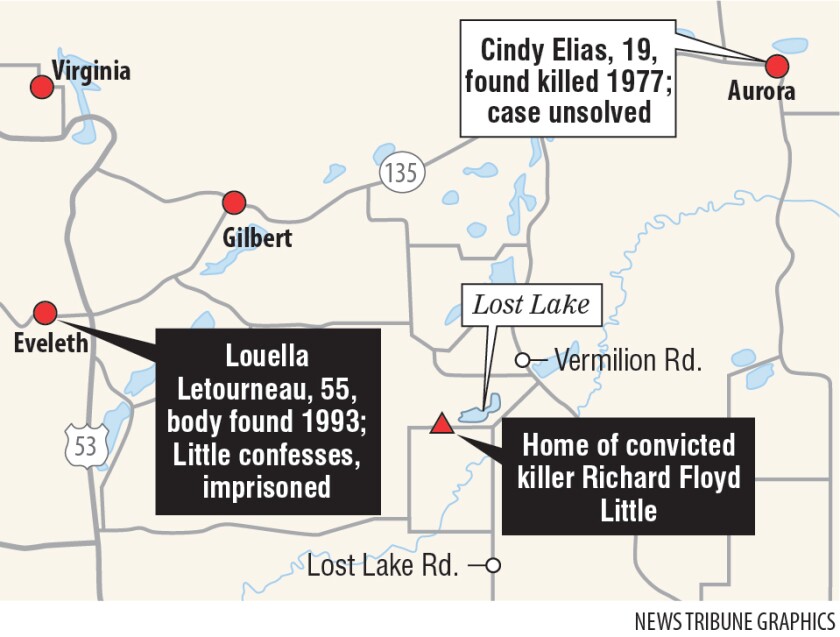

It’s a story of how the family grew up on a lake outside Gilbert, in the grip of an abusive man who terrorized animals and the people he was supposed to love. While the family members survived nightmarish ordeals, he would go on to become a convicted killer for the 1993 slaying and mutilation of 55-year-old Louella LeTourneau.

And before he died in prison in 2016, Richard Floyd Little — the ex-husband and father known as “Dickie” across the Iron Range — was nearly charged with the unsolved murder of Cindy Elias, 19, of Eveleth, from 1977.

Even in death, Little continues to be a credible suspect in the 44-year-old cold case.

DNA evidence collected from Elias’ crime scene in 1977 and reexamined within the past decade showed a familial match to Dickie Little’s DNA. But it wasn’t conclusively his, and, coupled with some contradictory evidence, it wasn’t enough for the St. Louis County Sheriff’s Office to refer charges to the county attorney.

“Everyone thought this was a good angle to go down,” said Lt. Nate Skelton, a supervising deputy and St. Louis County investigator based in Virginia who has been on the case for more than a decade. “But when we were starting to zero in, it just fell apart.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Investigators continue to hold out hope that improved technology will be able to drill further to determine if the DNA evidence from the Elias scene is, in fact, Little’s alone. They're prepared to resubmit evidence through the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, which has been aiding in Elias’ cold-case investigation for more than 10 years.

Few who knew him would be surprised if Dickie Little were to add to his body count.

“Nobody knows what it’s like when your dad is on the 6 o’clock news and they’re flashing his picture,” Michelle Little said, using her maiden name to protect her work as a social worker for the county. “It’s a different side of things, but it was our own misery.”

‘He was a know-it-all’

Judith Little died in 2015, eight months before her former husband died in a Stillwater prison.

Her family members called her Judy, and they lament how she never lived an adult day in her life without the specter of Dickie Little.

ADVERTISEMENT

By age 23, Judy Little had birthed four children — three boys, then Michelle — with Dickie. Judy survived two physical encounters with him that required the authorities to be called, and untold other abuses. She spent roughly 20 years married to him — more than she ever wanted.

“My sister stayed with him because she was afraid of him,” said Jean Newton, one of Judy's three sisters. Newton, 71, of Biwabik, lived two houses over on Lost Lake. That fact, and the loving kindnesses of all the aunts, provided safe haven for Judy and the children, Michelle said.

“If we wouldn’t have had that, it would have been horrible,” Michelle, 54, said.

Judy finally divorced Little after he’d found a girlfriend on the side. Dickie Little always had girlfriends. He came and went as he pleased. He knew every bar owner on the Iron Range, and cultivated a fun-loving persona around the area.

He loved to entertain at the lake, loved to hoot and holler at football-watching parties. Michelle talked about how she would always run into people telling her how much fun it was to water ski or carouse with her father.

ADVERTISEMENT

“But the people that knew him best, they knew what he was like — he was rage. He was just pure rage sometimes,” Michelle said as she told her story while seated on a picnic bench alongside Island Lake Reservoir in July.

“It forms who you are,” she continued. “You want to say you’re sorry. You know you’re not responsible, but you feel the guilt.”

Parented by a man keen to the vice of mental abuse, Michelle described difficulty trusting others. She said she expects perfection from people, having been told incessantly growing up how things "should" be done.

“He was a know-it-all,” she said.

Dickie Little exhibited classic abusive patterns, with Michelle saying he checked every box on the wheel of domestic violence, a tool used by social workers.

She witnessed him, in anger, shoot to death more than one family pet, and once discovered a discarded litter of kittens in the family’s garbage receptacle.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Now I have to go to school after I’ve found these kittens,” she recalled.

Cross Dickie Little, and he was likely to slash tires, or put sugar in a gas tank, she said.

One Christmas Eve, Dickie removed the presents from under the tree in a fury, canceling any hope of a glorious morning.

He poached game out of season, shooting turtles for soup, and drank the blood in ceremonial conquest of deer he hunted.

He threw cats from the dock, just to watch them swim, and beat his children for youthful transgressions such as getting caught smoking.

“He was very different around men,” Newton said. “He could harm little children, animals and women. But when men were around, he didn’t.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The family lived in fear of his presence. A capable logger, builder and trucker, they collectively sighed when he would drive away. To feel protected, Michelle slept with a knife and her twirling baton, which held vivid triggers from one evening before Thanksgiving.

In a bid to rekindle his marriage in 1979, Dickie Little brought a turkey to the house in hopes of creating an idyllic family meal.

“When she said no, he hit her,” Michelle said, describing how her father collected all of Judy’s belongings and lit them on fire in the yard, before taking the twirling baton and smashing to pieces everything in the house.

By 1993, he’d long since fulfilled a one-year sentence at the local work farm for those transgressions, and Dickie Little was off the authorities’ radar. He’d seen a second wife die after what family said were struggles with alcoholism. He was on the prowl. That’s when he dated, and then began stalking LeTourneau after she decided to reconcile with her husband.

News Tribune reports from the time detailed how her friends and family had grown concerned for her safety even prior to her going missing Dec. 13, 1993. But as is the contradiction with Dickie Little, the newspaper stories from the day after he was apprehended included sunny references in headlines. The main article announced him as a “former friend held in death,” while an accompanying story referred to the killer as a “nice guy.”

Did Dickie Little kill Cindy Elias?

LeTourneau was killed on a bridge over the St. Louis River. Michelle hates that fact, because she and her brothers used to swing and jump into the water from that bridge. LeTourneau’s body was found several days later, away from the bridge, in a wooded area known by logging types in Makinen, she’d been shot, stabbed, hauled around in the bed of Dickie's pickup truck, and mutilated in disturbing ways.

Sixteen years earlier, within hours after people feared Cindy Elias' disappearance, her body was discovered off a logging road outside Aurora. She’d spent a night out on the town in Virginia, and the last person to see her remembered her looking for a ride home, according to an NBC News report from 2017.

Elias’ body was found badly beaten, with multiple traumas to the head. The brutality and the remote locations of the bodies are two details that linger from both cases.

“There are vague similarities, but the difference is he was romantically involved with Louella,” Skelton said. “She was going back to her husband, and that set him off.”

Elias’ case is the oldest cold case in St. Louis County, and one that brings family members into the sheriff’s office every anniversary to learn what’s being done in pursuit of justice. The family is privy to the information contained in this story, authorities said. The News Tribune did not connect with the family in time for this report.

In several interviews with authorities, they say Dickie Little emphatically denied ever having contact with Elias.

But his familial DNA evidence is related to the Elias crime somehow. The layman might conclude he’s the killer. What’s stopping the authorities?

For one, a relationship between Dickie Little and a person St. Louis County authorities termed “a jailhouse snitch.” Skelton, Sheriff Ross Litman and Undersheriff Jason Lukovsky described existing evidence that shows the two men cooking up a scheme to get reward money. The man would feed Little known details about the crime, while Little planned to confess and split the reward money.

“He was working extensively with that guy," Skelton said. "When we’d go through their phone calls, he was basically being spoon-fed a lot of the information he was putting in letters and telling authorities about."

Had the county charged Dickie Little using the impartial DNA evidence, a defense attorney would have used the snitch information to blow apart the prosecution’s case, the authorities said.

“It’s our duty to disclose information not favorable to our investigation,” Lukovsky said about the snitch intelligence.

“If you try it and fail, you know what happens if you lose it,” Litman added, referencing the law against being tried for the same crime twice. “You only get one shot at it.”

The authorities described the partial DNA profile in the Elias evidence as a hit on the Y chromosome.

“It more goes to the lineage of the male side of the Little family,” Lukovsky said.

Dickie Little had a brother, who is now dead, too, Michelle said, describing him unkindly.

Elias’ body was exhumed based on information from a tip a number of years ago. There was nothing recovered that was of evidentiary value, Skelton said, meaning the DNA the authorities are prepared to revisit once again was originally collected in 1977.

Part of the technological enhancements in DNA testing are related to the ability to get more information from a smaller sample — possibly the difference between a full DNA profile, instead of a partial one.

Of course, Dickie Little won’t be alone when it comes to further scrutiny. Skelton said there are "hundreds of known DNA profiles of people involved with the Elias case file." Any one of them could come back from a reexamination with a clearer picture of how to move forward.

“At this point, we can’t completely rule Richard Little out,” Skelton said. “We can’t rule anybody out.”

Postscript

Jean Newton recalled once taking her sister to the threshold of the local newspaper. The authorities had been in contact with the family, explaining they were looking at Dickie Little in the Elias case. Judy Little wanted to read more about the events of 1977.

But before they got to the door, she changed her mind. She’d had enough of the past, her sister said.

“We got as far as the step, and she said, ‘I can’t do this,’” Newton said. “I don’t think she wanted to learn any more about the person she was with for so many years; it was overwhelming.”

That’s when Newton knew Judy Little was never going to tell her story.

“It’s also, like, my story, too,” Michelle said, coming to grips with her own apprehension.

She lives on the East Range, and is married to a miner. They have an adult son, who didn’t learn about his grandfather until he was 18, shrugging it off.

“Nothing phases my son,” she said. “I should have known that.”

Michelle went to see her father in a St. Louis County courtroom in March 1994. She said she and one of her three brothers filed into the back for his sentencing hearing after he’d confessed to killing LeTourneau.

“When they got him up, we stood up, so he saw us,” Michelle said. “He knew we were there. It was like, ‘You can’t pull the wool over our eyes.’ That was the last time I saw him.”