FARGO — Early during the first morning of North Dakota’s largest drug trafficking trial to date, the prosecutor, the defense attorney and the federal judge met behind closed doors on Dec. 31, 2002.

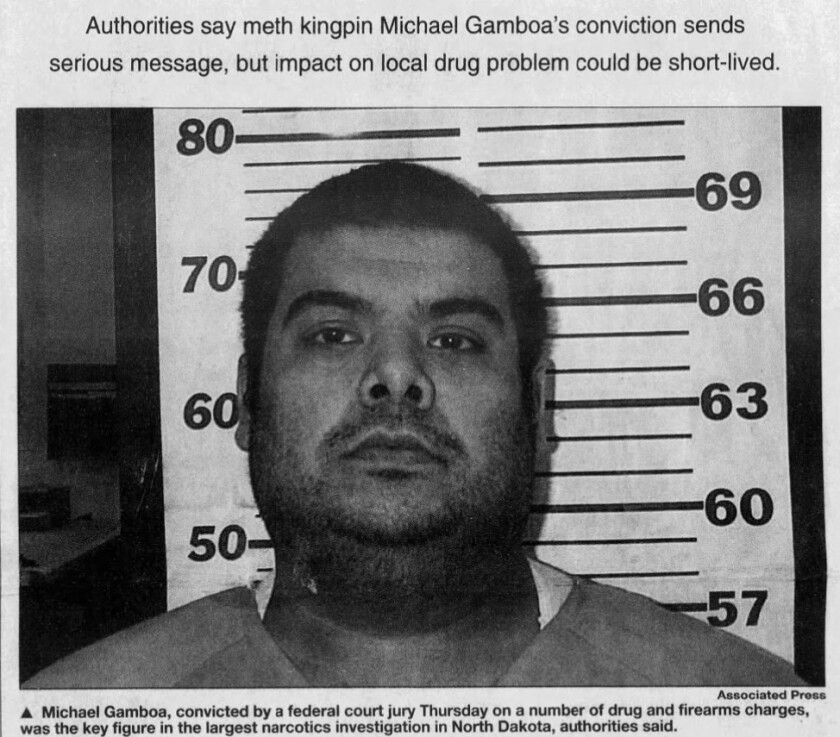

Inside U.S. District Judge Rodney Webb’s chambers, Assistant U.S. Attorney Keith Reisenauer and James Hovey, attorney for Michael Gamboa — 27-year-old drug kingpin and ringleader of what newspapers called “meth mayhem” across the state — appeared troubled, according to trial transcripts, available only in paper at the Quentin N. Burdick U.S. Courthouse.

ADVERTISEMENT

“He (Hovey) told me that there was a hit out for my life … it was made by an individual known as …” Reisenauer began telling the judge.

“El Kaote,” said Hovey, interjecting.

Despite all of the trial discovery, nobody had ever heard the name. They all knew the case dove deep into organized crime, perhaps all the way to Mexico’s ruthless drug lords who would stop at nothing to protect their interests. Now, there was a supposed hit from an unknown assassin on one of the prosecuting attorneys’ lives.

Gamboa and his drug dealers all had nicknames; the top distributor was called “Ma,” another dealer was called “OxyScottin,” and Gamboa’s was “M.”

Hovey believed that Gamboa was in the methamphetamine business with the Mexican Mafia, or La eMe, Spanish for “The M,” by The Forum.

The threat was real, said Webb, who had received many during his three decades of government work, and violent tax protester, in 1983.

“I’d ask you to keep yourself open as far as threats being broader than directed at one individual," Webb said, adding that for safety reasons, jurors could be quartered at a local hotel and be driven to the federal courthouse basement under police protection.

ADVERTISEMENT

To keep the courtroom safe, U.S. Marshals posted four agents inside.

The trial must go on, Webb said.

Gamboa’s rise

Paper trial transcripts and court documents, only available at the U.S. federal courthouse in Fargo, reveal Gamboa’s rise to a drug-trafficking kingpin.

Gamboa was a small-time marijuana dealer in 1996, but he saw opportunity when meth hit the market and began distributing on a small scale in 1999 out of Grand Forks, according to court documents. His older brothers, Robert, who was already in jail, Rolando and Edward followed the same dark path.

Gamboa and his crew were dealers, but they also used their own product — regularly. Dealers were primarily paid with meth, which they smoked and sold.

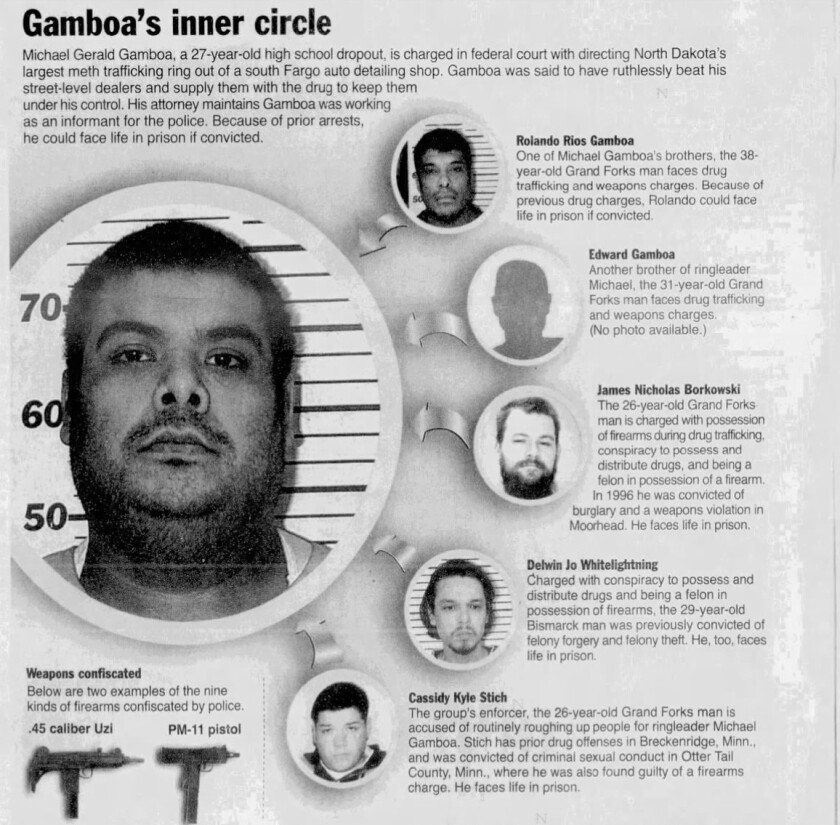

By 2001, Michael Gamboa’s inner circle consisted of his brothers, Rolando Rios, 38, Edward, 31, both of Grand Forks; James Nicholas “Bork” Borkowski, 26, dealer and bodyguard; Delwin Jo “DJ” White Lightning, 29, who ran the meth ring from an auto shop on Airport Road in Bismarck, and Cassidy Kyle Stich, 26, dealer and enforcer.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many of the street dealers Gamboa found first came to him for a high, like Aaron Allen, who cleaned cars out of an auto shop on Dyke Avenue in Grand Forks. Over time, Gamboa muscled in and the business scope turned to distributing methamphetamine, which Allen bought for $800 an ounce.

When Gamboa moved operations to Fargo, his first shop was in north Fargo. Soon after, he moved to a “fortress” at 2705 5th Ave. S. The building was large and L-shaped, sandwiched between 27th Street and 5th Avenue, and had numerous bases or stalls, with doors attached to individual offices.

Gamboa, a high school dropout, lived there, and he lived well. He had a snowmobile and a speedboat. Inside the shop, there was a place to shower, a bedroom, a hot tub, a mock fireplace, a living room with a lounge, a large-screen television, a safe and a refrigerator.

He also had digital scales, heat sealers, pounds of meth and car trunks full of assault weapons.

The building, owned by Fargo landlord Pete Sabo, was home to many operators, some of whom ended up working with Gamboa, and some who were too afraid of him to call the police and tried to mind their own business.

Gamboa had other dealers like Kandy “Ma” Walter-Leach out of Grand Forks, the top seller who by 2001 had been arrested six times on drug-related charges. She sold about 10 pounds a week, and paid him more than $800,000 in cash.

Walter-Leach, Allen and his inner circle were only a few of his dealers; Gamboa had at least 16.

ADVERTISEMENT

Gamboa’s secrets

As a twice-convicted drug dealer, Gamboa protected a secret that could get him killed if the wrong people found out: he became a confidential informant for the North Dakota Bureau of Criminal Investigation on Aug. 22, 1996.

He provided little helpful information, however, but on Feb. 24, 2000 — a year after he began setting up his drug empire —he managed to sign another CI contract, promising to help federal agents take down his suppliers.

As an informant, there were rules. Gamboa was not allowed to carry guns or break any laws, and all drug deals had to be supervised by his handler.

Kathleen Murray, an agent with the NDBCI, told the court during Gamboa’s trial in 2002 that she believed Gamboa’s family connections to the underworld made him a good informant, but a few months after he signed the second contract, she deactivated him.

“He was no longer needed and it was too late to do anything,” Murray said.

His crew were not the cartel, they were not mafia, they were modern-day mobsters “seeking control of a secret market from a gated fortress,” according to a Dec. 29, 2002, news article published by The Forum.

ADVERTISEMENT

But he had connections to the Mexican Mafia, Hovey argued in court.

A group of Mexicans that Gamboa referred to only as “Chicago” or “Minneapolis” delivered 5 to 20 pounds of meth to his Fargo garage regularly — before it was redistributed across the Red River Valley and wider region.

One of Gamboa’s suppliers, Rudolfo Torres, a Mexican citizen who paid $1,200 to be smuggled into the United States by coyotes, would drive a car into a stall late at night. Dealers would then open hidden compartments — built into airbags, behind quarter panels or back seats, or beneath the hood — and extract pound-sized round packages wrapped in gray duct tape.

People like Stich then split the packages open, weighed and then separated the meth into smaller baggies for sale.

While Gamboa allowed walk-in customers, the majority of his meth was sold in bulk. John Anderson, of Grand Forks, bought meth for $11,000 per pound.

“Just drove in a door and did the deal and more or less left right after that,” Anderson testified in court. It was just like getting a meal through a drive-in, he said.

ADVERTISEMENT

‘We are going to have a crisis’

Meth was available in North Dakota and Minnesota before Gamboa’s mayhem, but he quickly became the largest local distributor, solidifying dealers and smuggling routes, according to court documents. He became arrogant, saying Grand Forks belonged to him, and that “In another life, he would have been a king,” Stich testified in court.

The damage meth created was quick, leading to intense paranoia and violence.

The drug was cheap: $20 for a 10-hour high.

“Almost all of the drugs that come to the U.S. come from Mexico,” Torres testified.

The year Gamboa’s drug empire began, Reisenauer issued a warning: “I think it’s a major problem in the state because of the danger of the drug. If we have a continued increase, we are going to have a crisis,” in March 1997.

Five years later, Gamboa’s drug ring — based out of three auto repair shops in Bismarck, Grand Forks, and the Fargo “fortress” — had distributed more than 400 pounds or $18 million worth of meth, but an internal rot, a drug-induced paranoia, intensified as the Red River Valley Task Force, backed by at least 13 law enforcement agencies, turned their collective attention toward the south Fargo auto shop.

Next story >>>