Editor's note: This archival article was in the Rochester Post-Bulletin on May 20, 2022.

ROCHESTER — On a cold October afternoon in 1925, with the World Series about to get underway in baseball’s Major Leagues, roughly 2,000 baseball fans packed Mayo Field to see the only local appearance that season by a local favorite—who also happened to be one of the more infamous ballplayers in World Series history.

ADVERTISEMENT

Charles “Swede” Risberg—the former Chicago White Sox player who had been banned for life by Major League Baseball after allegedly conspiring with gamblers to throw the 1919 World Series—was pitching that day for the semipro Rochester White Sox in a “Little Series” game against the Rochester Aces.

And he didn’t disappoint. Soon after the umpire declared “Play ball!” Risberg drove in the first run of the game with a triple.

But after struggling in the chilly weather and throwing two wild pitches in the third inning, Risberg left the pitching mound and moved to second base. There, he “thrilled the stands with a spectacular catch of a hard-hit drive that carried on it all the marks of a double,” the Post-Bulletin reported. Despite Risberg’s efforts, the White Sox lost the game, and the Little Series, to the Aces.

Risberg’s popularity — from baseball barnstorming in Minnesota, across the Dakotas and elsewhere — was quite a turnaround from three years earlier, when his signing with the Minnesota club had caused some consternation in baseball circles.

‘Frequent fisticuffs, toughness, excitability, and standoffishness’

Born in San Francisco in 1894, Charles August Risberg was the son of a Swedish-born longshoreman father and Danish immigrant mother. He survived the Great Earthquake of 1906, was a star pitcher for his school by age 14, and, at age 17, tried out for—and was signed to—the Pacific Coast League.

After five years in the minor leagues, the Chicago White Sox called Risberg up to the majors in 1917 as a shortstop with a strong arm and weak bat. He was, according to the Society for American Baseball Research, known for his “frequent fisticuffs, toughness, excitability, and standoffishness.” After one game against the Detroit Tigers, he reportedly fought Ty Cobb to a draw.

Risberg, considered one of the league’s best fielding infielders, hit only .203 in his rookie season, but improved to .256 each of the next two years, including in 1919, when the White Sox were regarded as the finest team in baseball. They were heavily favored to win the World Series that year against Cincinnati.

ADVERTISEMENT

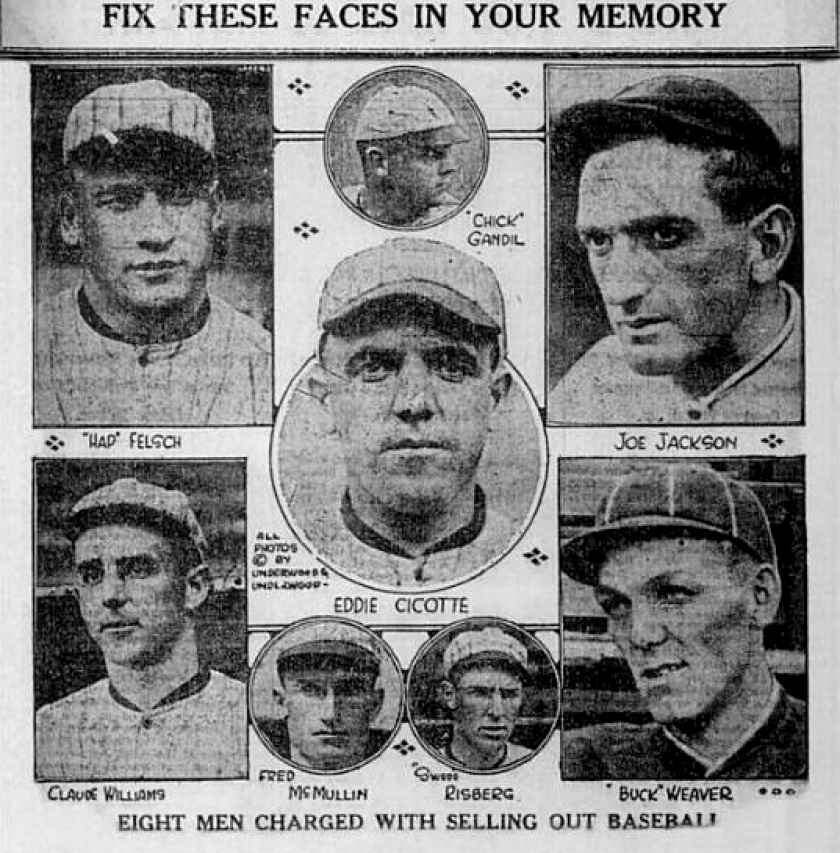

However, tempted by gamblers offering significant payouts, eight of the Sox, including Risberg, allegedly conspired to lose the series in what became known as the Black Sox scandal.

The Sox lost the best-of-nine World Series five games to three. Risberg hit .080 and committed four errors in eight games.

Though he was just 25 and in his third year in the Majors, Risberg was considered to be one of the ringleaders of the plan.

His 1919 baseball salary was roughly $3,500, his payout for his part in the “fix” was rumored to be $15,000.

A year of investigations followed, and the players ended up in a courtroom facing criminal charges.

They were acquitted by a jury, but all eight players were suspended from Major League Baseball for life by Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the new baseball commissioner. They had to find other places to play ball.

ADVERTISEMENT

‘Former Chicago White Sox pitcher is signed to play with Rochester team’

In 1921, Risberg and a few other of the so-called “Eight Men Out” formed the Ex-Major League Stars and barnstormed across the Midwest, taking on teams in northern Wisconsin and Minnesota.

At the same time, Risberg’s first wife, Agnes, filed for divorce. She got custody of their two kids.

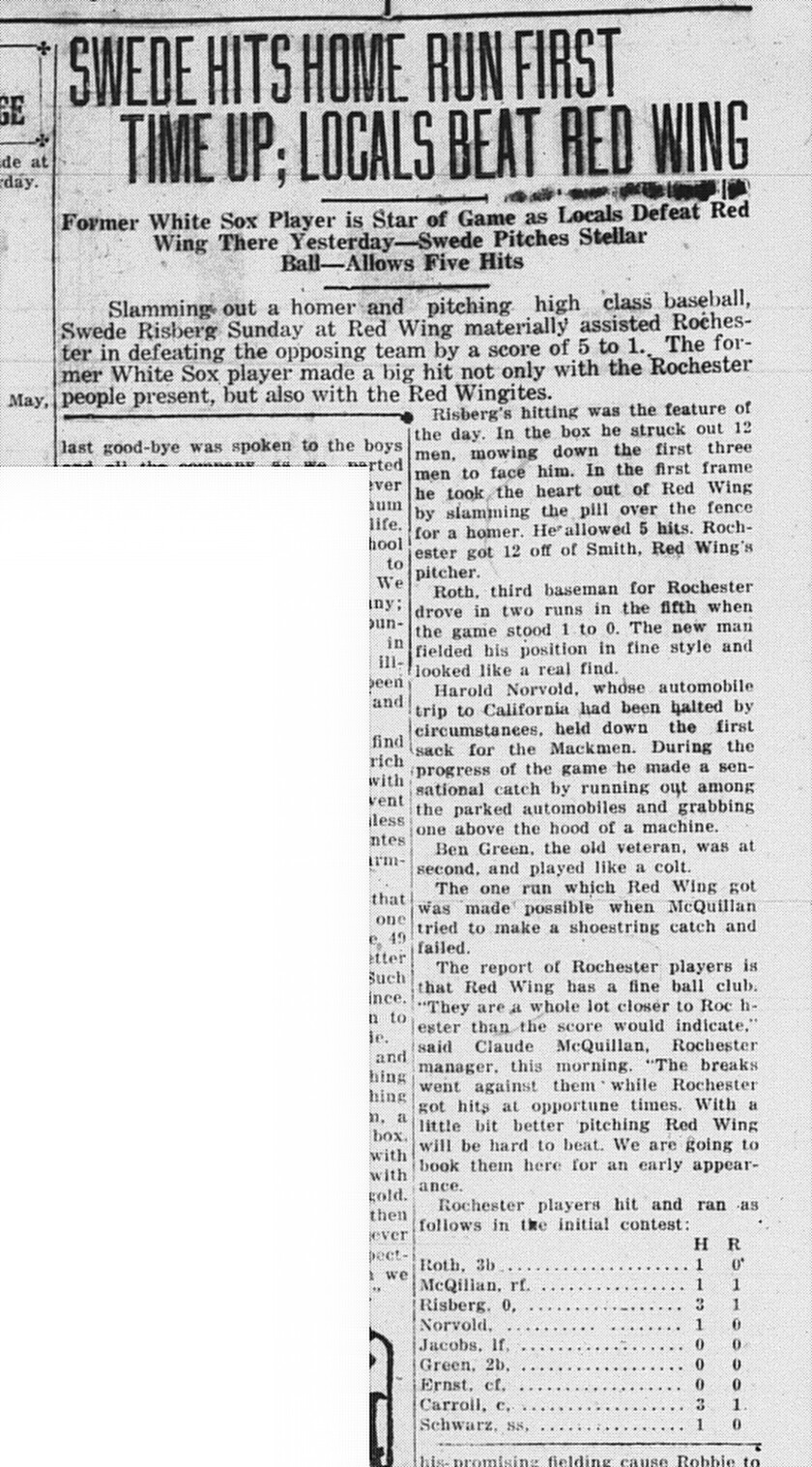

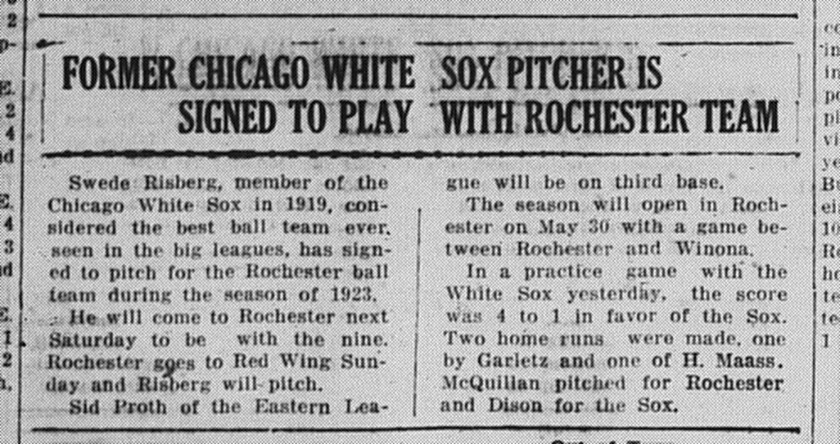

On May 21, 1923, a small announcement appeared on in the Rochester Daily Bulletin: “Former Chicago White Sox pitcher is signed to play with Rochester team.” Swede Risberg would pitch for Rochester in the season-opener the following Saturday in Red Wing.

When Twin Cities newspapers raised questions about a suspected cheater playing for Rochester, local fans rallied around the newcomer. “The past is the past,” quoted the Daily Bulletin. “He’s a good ball player and should be permitted to play.”

Risberg repaid the loyalty by hitting a home run in his first at bat of the season, and for good measure also started the game as a pitcher and struck out 12 batters. Two weeks later, on Memorial Day, Risberg pitched at Mayo Field for the first time and struck out 10 batters, including five in a row at one point, in a 7-6 win over Winona.

Risberg’s strong arm had been his calling card as a Major League shortstop, but it was a real weapon for a pitcher throwing to semipro batters across southern Minnesota. For the 1923 season, Risberg posted a 20-5 record (with 200-plus strikeouts) as a pitcher. He hit .382.

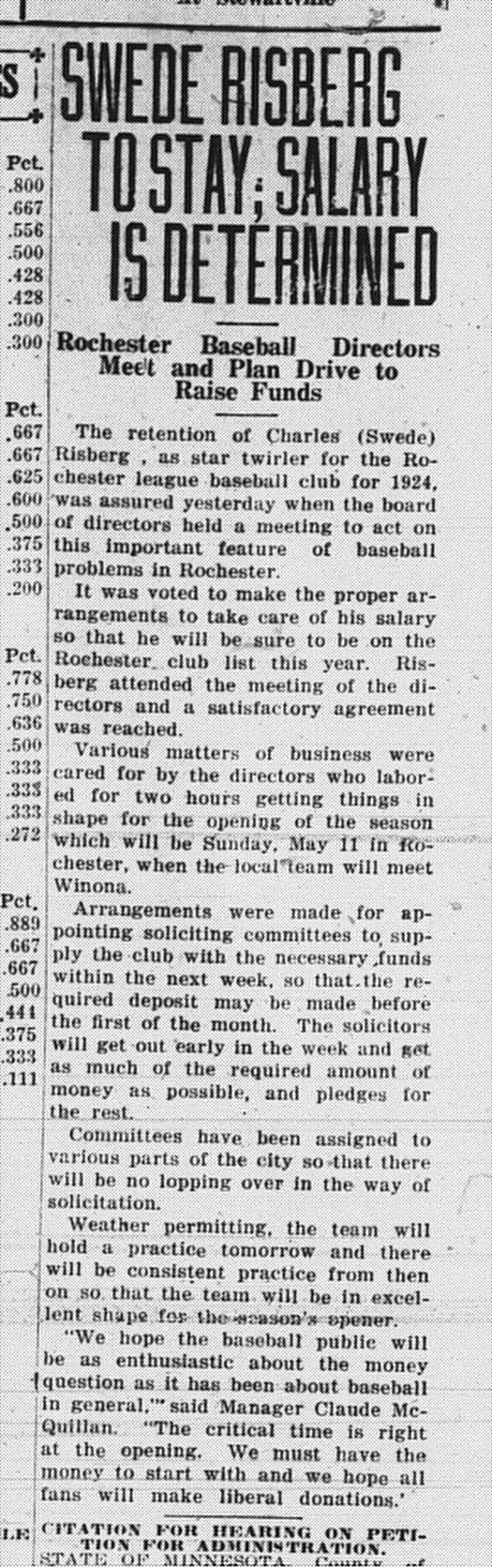

During the following winter, “It was voted to make the proper arrangements to take care of his salary so that he will be sure to be on the Rochester club list this year,” the Daily Bulletin reported.

ADVERTISEMENT

Meanwhile, on Jan. 12, 1924, Risberg married Mary Frances Purcell, a Rochester dental office worker. They bought a farm in Rochester Township, and started raising a family. The Risbergs reportedly sold eggs and other produce from their farm to Mayo Clinic.

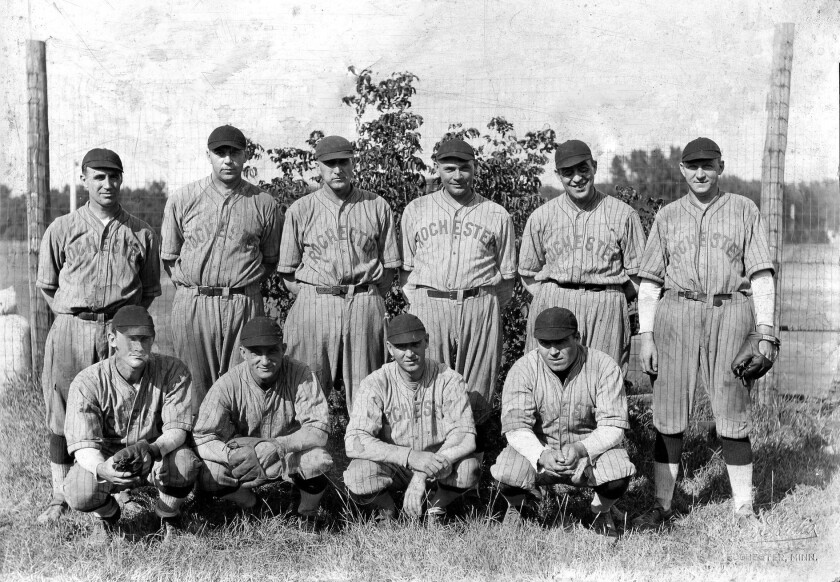

Risberg and Rochester Aces manager Claude McQuillan started training for the 1924 season even before all the snow had melted.

Born in Rochester in 1888, Claude “Boney” McQuillan was a sports standout at Rochester High �������� and played semipro baseball, boxed professionally, and played semipro football (for the Green Bay Packers in their pre-NFL days). He would later serve as Rochester’s mayor from 1947 to 1951 and again from 1953 to 1957 (when he died in office).

“Swede and Mack went through some catching performances to start their arms going,” the Daily Bulletin reported on March 28.

The early work paid dividends: In the season opener, Risberg walked the first batter he faced, then held Winona without a hit until the ninth inning. For the 1924 season, Risberg won 22 games as a pitcher and hit .361.

But, in 1925, the Aces were forced by the Southern Minnesota League to recognize organized baseball’s ban on Risberg. Risberg had to leave the team before the 1925 season.

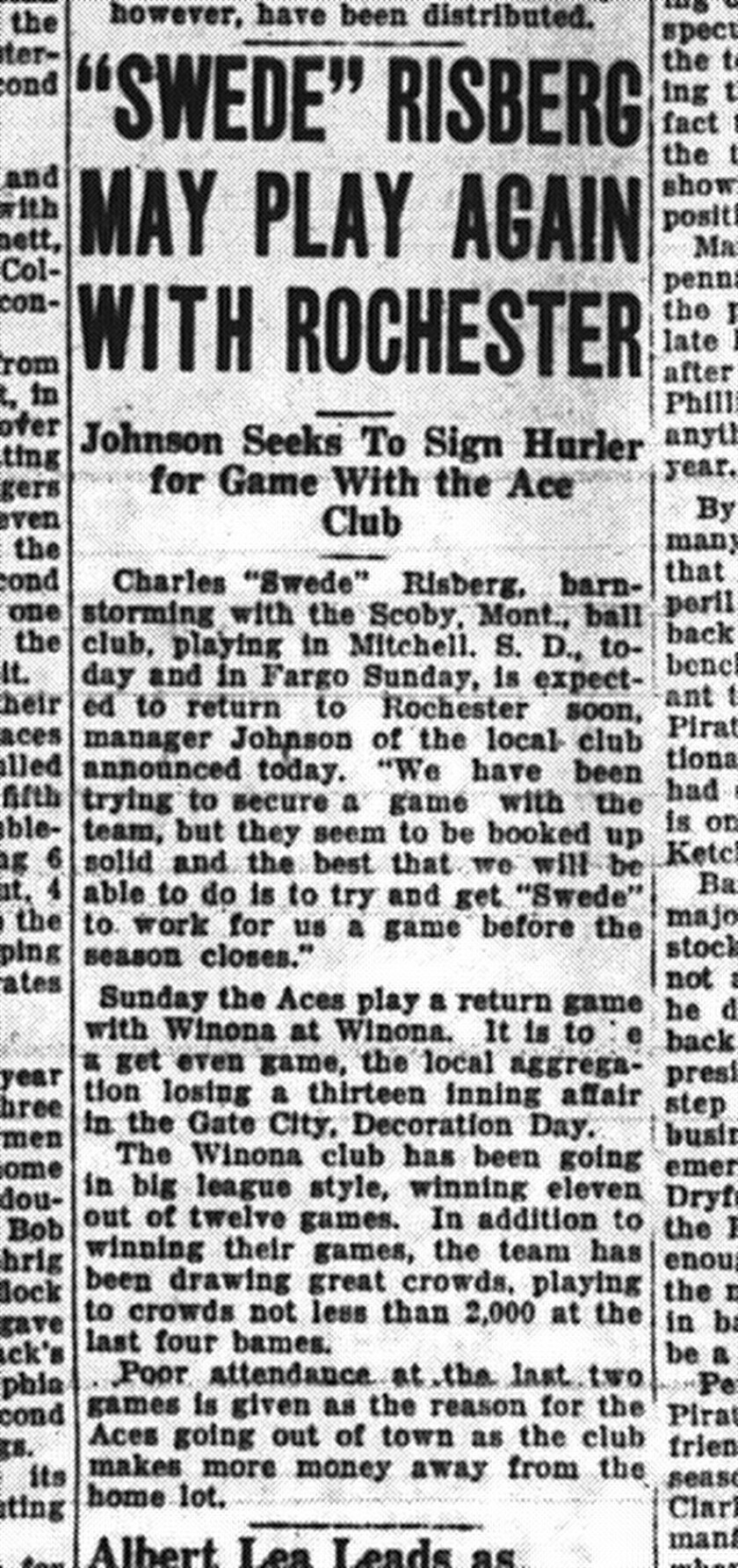

Risberg signed with a semipro team in Montana, and temporarily left his wife and his farm in Rochester during the 1925 season to barnstorm across the West.

ADVERTISEMENT

Then, at the end of that summer, he came back for that one game in front of Rochester fans.

When the 1925 season ended, Risberg went back to working on the farm. He also invested in the Zumbro Auto Company in Rochester. Son Robert was born on November 29, 1925 in the Mayo Clinic.

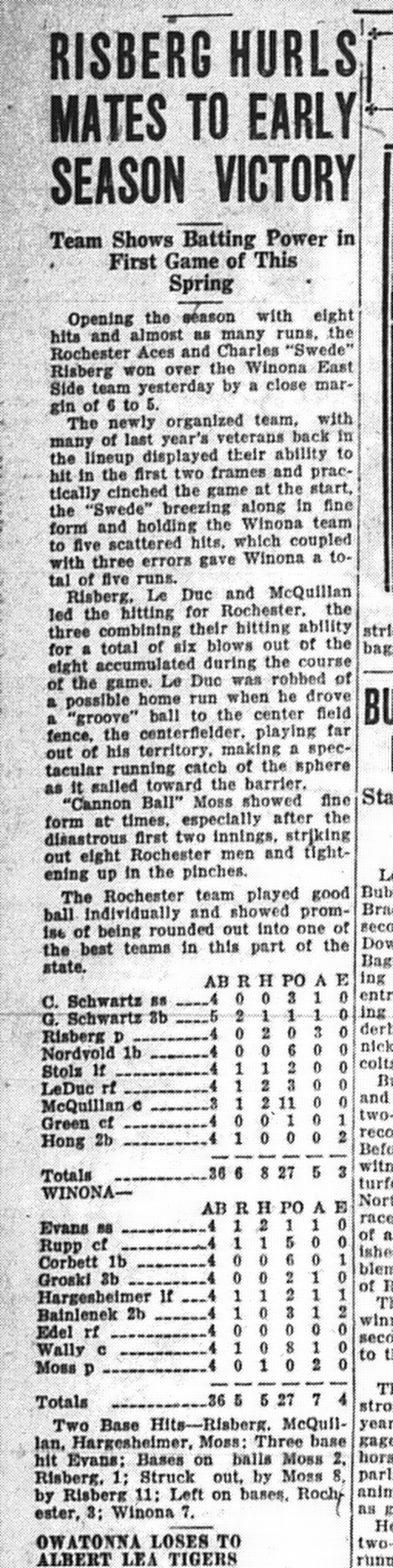

When the spring of 1926 came around, Rochester baseball supporters began putting together an independent team, which coincidentally would not be hindered by Risberg’s ban from organized leagues.

“Yes, I want to play in Rochester this year,” Risberg told the Post-Bulletin. “I want to be near here to take care of my farm.”

So when the Rochester Aces opened their season on May 17, it was with “the ‘Swede’ breezing along in fine form and holding the Winona team to five scattered hits,” according to the Post-Bulletin.

In late July, though, Risberg informed McQuillan that he was leaving the club. Despite having won nine out of 10 starts, Swede “said that his arm is not as strong as it was,” reported the Post-Bulletin. He ended up playing the rest of that summer for a team in South Dakota.

He went on, over the next decade, to play on teams from Wisconsin to California.

ADVERTISEMENT

McQuillan, for his part, reached out to two other members of that infamous 1919 White Sox team to replace Risberg. On July 21, 1926, the PB reported that wants to sign Dickey Kerr, one of the White Sox players who was not implicated in the cheating scandal (he won two games in the 1919 World Series), or Eddie Cicotte “one of the best spitball pitchers that ever played in the big leagues.” And one of the banned White Sox players.

‘He loved baseball too much to ever quit’

“Baseball was my father’s life,” Risberg’s son Robert told us in a 2006 interview. “Just when he was at the top of his game, he could no longer play in the Major Leagues. He had a hard time with that, but he loved baseball too much to ever quit.”

In 1929, the Risbergs lost everything in the Wall Street crash, Robert said. “Everything he had earned from playing baseball was gone,” he told us. “Our home, our farm, our part of the car business. But my father kept playing baseball, and kept working hard.”

Swede and the family moved slowly west, to South Dakota then Oregon then finally settling in his home state of California. Swede worked in the lumber business for a few years. Tended bar in taverns.

Mary, Swede’s wife of more than 35 years, died in 1960.

“I remember my mother telling me how wonderful Mary was and what a strong and loving woman she was,” says Jeff Risberg, Robert’s son, who lives in St. Paul. “I remember that my dad (and I assume his brother) was born in the Mayo Clinic. I also remember hearing that the young family lived on eating a steady diet of pheasants one winter, so much so that my dad never liked the taste of pheasants ever again (but he loved hunting them).”

Swede moved in with his son Robert soon after Mary died.

“Even then, he was watching and listening to every baseball game he could,” said Robert.

Charles “Swede” Risberg died in Red Bluff, Calif., on Oct. 13, 1975, his 81st birthday. He was the last of the “Eight Men Out.”

He was buried next to Mary in Mount Shasta, California.

Risberg was undoubtedly one of the most talented players ever to take the field in Rochester. Ironically, he was playing—and starring—in the lower minor leagues only because he had been accused of cheating on baseball’s biggest stage.

Newspaper Clippings