EDITOR'S NOTE: This archival article was first published on June 8, 2002.

WAHPETON, N.D. — It stands on a large plot, dwarfing headstones of what was once called the Bohemian Cemetery.

ADVERTISEMENT

It resembles a broken pole, wound with a rope and pulley system. The likenesses of a hammer and tent stake protrude from the structure's base.

Etched into that base reads: "Erected by the employees of Ringling Bros. Circus. Charles Smith, June 10, 1897; and Chs. E. Walters, Sept. 15, 1870 — June 10, 1897."

It's a monument in Wahpeton, North Dakota, to two men and a strange little episode in North Dakota history — one many residents have never heard and some circus workers will never forget.

Lightning crashes

Wahpeton was buzzing the morning of June 10, 1897.

The Ringling Bros. Circus train was pulling into the Great Northern Depot, having just finished shows in Fargo, Grand Forks and Devils Lake.

White horses and wild animals never seen by many people in the area were unloaded, according to newspaper articles.

Edward Williams, a 12-year-old boy at the time, recalled his own special circumstances about the day 63 years later:

ADVERTISEMENT

"That was the first time I saw a hippopotamus," he said. "The animal was lying in its cage like a big hog.

"I was up before dawn that day. I wanted to be one of the first to get a job."

Ringling Bros. used to give free show tickets to kids who would help set up the grounds and tents.

Williams and several other boys were hired to help hoist the big top tent, a mammoth task given the persistent rains that began that morning.

The crew foreman cut holes in the canvas folds to free the water and lighten the load, but the boys still couldn't muster the strength to leverage the ropes of the tent into place, Williams recalled.

A dozen or so circus workers stepped in.

"I was pulling on the rope when one fellow pushed me aside and said, 'This is a man's work,'" Williams said.

ADVERTISEMENT

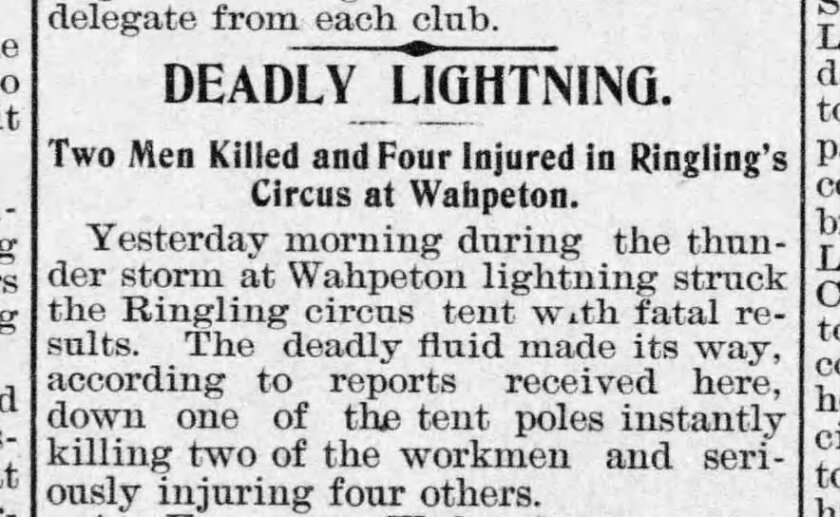

Just at that moment, lightning struck the main tent pole, instantaneously killing Smith and Walters, gravely injuring foreman Charles Miller — who would die from his injuries a year later — and knocking unconscious at least a dozen other nearby circus roustabouts and performers.

In its June 10, 1897, afternoon edition, the Wahpeton Times reported: "While Ringling Bros.' canvas forces were at work putting up the main tent this morning, a thunder shower came up and a shock of lightning struck one of the main poles, killed two men outright, and severely stunned three others."

Historian Lowell Torgerson wrote: "Other people affected by the lightning bolt were revived by circus employees who tore off the shoes of those that were unconscious and pounded the bottom of their feet and the palms of their hands."

In 1960, Williams couldn't recall if any of the other boys were harmed, "But my family always said I was as white as a sheet for two days afterwards," he said.

The show goes on

Despite the tragedy, it was felt the afternoon circus and its preceding parade should be held.

"The parade was the largest and finest ever seen in the city," according to Wahpeton's Richland County Gazette on June 11, 1897.

This, despite the hard rains, which mired the parade route and forced elephants to push out horse-drawn carriages and cages that became stuck in the gumbo on their way to the circus grounds, also the site of the former Rosemead Pottery building.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Gazette reported the parade was made up of "205 beautiful horses, 51 carriages, 31 small ponies, 12 elephants, 5 camels, 4 bands, 1 calliope and 1 chime of bells."

More than 7,000 people were reported to have attended the circus' afternoon show.

"This was really the golden age of the circus," said Meg Allen, an assistant librarian at Circus World Museum in Baraboo, Wisconsin.

Baraboo was the winter quarters of the five Ringling brothers — Al, Alf, Auto, John and Charles — from 1886 to 1918. The circus would begin its nationwide summer train tours in Baraboo and, at each stop, would entice people to attend the shows with its spectacular parade.

"The parade was the culmination of the advertising campaign," Allen said. "It was a very big deal."

Wahpeton's North Dakota Globe newspaper reported on the circus one week after the tragedy:

"Everything was under control, no swindling games were allowed, almost no profanity was heard. That the management has the interest of the workmen at heart was shown in the concern felt at the death of two by lightning bolt."

ADVERTISEMENT

Paying last respects

Following the afternoon show, circus workers gathered their earnings to pay for Smith and Walters' burial.

Friends and families of the two circus workers asked that the two be laid to rest in Wahpeton, where they died.

More than $500 was raised — enough to cover funeral expenses and a granite monument to the men. It's unclear if the money came solely from circus workers or from those attending the shows that day.

From June 10 to Sept. 29, 1897, a makeshift marker of the lightning-shattered tent pole overlooked the gravesites, with part of the rope and pulley system used to hoist the canvas big top.

Nobody knows who made the granite marker, but it is said to be patterned off a photo of the makeshift one.

Circus workers nationwide have been known to visit the site on occasion — especially when a circus comes to the Richland County area.

While honoring Smith and Walters, some are taken aback by another much-smaller monument less than three yards away.

ADVERTISEMENT

It marks the gravesite of Herbert "Duke" Joseph Walker, a Lafayette, Louisiana, man who worked with the Daily Bros. circus and died of a ruptured appendix while putting on a show in Wahpeton in 1948.

"I know there's definitely truth to that pilgrimage thing," said Allen.

She cites Wahpeton's entry in the

"At this town the saddest accident of the season occurred," it states, then goes on to explain the tragedy and the monument later placed over the graves.

"The monument represents a shattered center-pole, upon a substantial base, and is properly inscribed to commemorate the sad affair, as well as to perpetuate the memories of those whose lives went out at the lightning's flash."

As for Williams' free pass to the circus, he never got it. The man who was in charge of his crew that day died.

During the parade, Williams recounted how he saw an important-looking man astride a white horse.

"I worked at the tent, but I didn't get my ticket," Williams shouted up to the man.

"Well," said the horseman, "where's your foreman?"

"He's dead," Williams said.

"That's hard luck," remarked the horseman, who then rode away.