FARGO, N.D. — Forty years after Cindy Gerdes was brutally murdered, her brother, Michael Gerdes, scrolled through a digital copy of the Minneapolis police case file. He, and his sisters, Claudia Gerdes and Mary Broberg, had never seen the information before.

While the three of Cindy’s eight siblings learned facts about the 1984 case, Michael spoke out against the claim former Minneapolis Police Chief Tony Bouza issued in 2021. Bouza appeared to be haunted by 28-year-old Cindy’s murder, and on his website, Southside Pride, in 2021, two years before his death.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Unfortunately, Cindy Gerdes had no champions — press or family — clamoring for results. These interventions can matter," wrote Bouza, the Minneapolis chief from 1980 to 1989. “My guess is that her killer has been collaterally arrested many times in the intervening decades — yet there is no evidence of any police interest. This is a tragedy and an outrage.”

That characterization didn’t sit well with the Gerdes family.

“I really take exception to him saying that there wasn’t enough clamoring by the family and friends, because we clamored. Talking to the police and the FBI and not getting any results from that. It is really unfair that he said that,” Michael said.

“We got nothing,” Claudia said, adding that police typically told them the case was still an open investigation and they could not share details. Forum News Service received the Minneapolis police case file last month, but the department has not answered additional questions.

“They wouldn’t even talk to us,” Michael said. “We had to be asking them for information about what happened. There is no playbook on how to handle the police department after a sibling has been murdered. We knew nothing.”

The Gerdes family, who grew up in Moorhead, Minnesota, even Cindy’s best friend and college roommate, Mary Kloster, knew only what the newspapers reported. Citing an open investigation, the Minneapolis police detectives told the family very little over the years.

At Shanley High ��������’s 50th class reunion in Fargo, North Dakota, this year, Kloster read Cindy’s name aloud during memorial mass. Friends who knew Cindy during the early 1970s later asked her questions.

ADVERTISEMENT

All Kloster could say was that Cindy’s case still has not been solved.

Cindy lived with Kloster even after she transferred to North Dakota State University to study interior design and architecture. When Kloster got married, her husband’s cousin Janet and Cindy ended up rooming together in Minneapolis, Kloster said.

The women lived together until Janet married a man named Patrick Thomas Walsh — later divorced in 1993, according to Minnesota court records — who at the time was well-liked by family and friends. Nobody thought to check his criminal background.

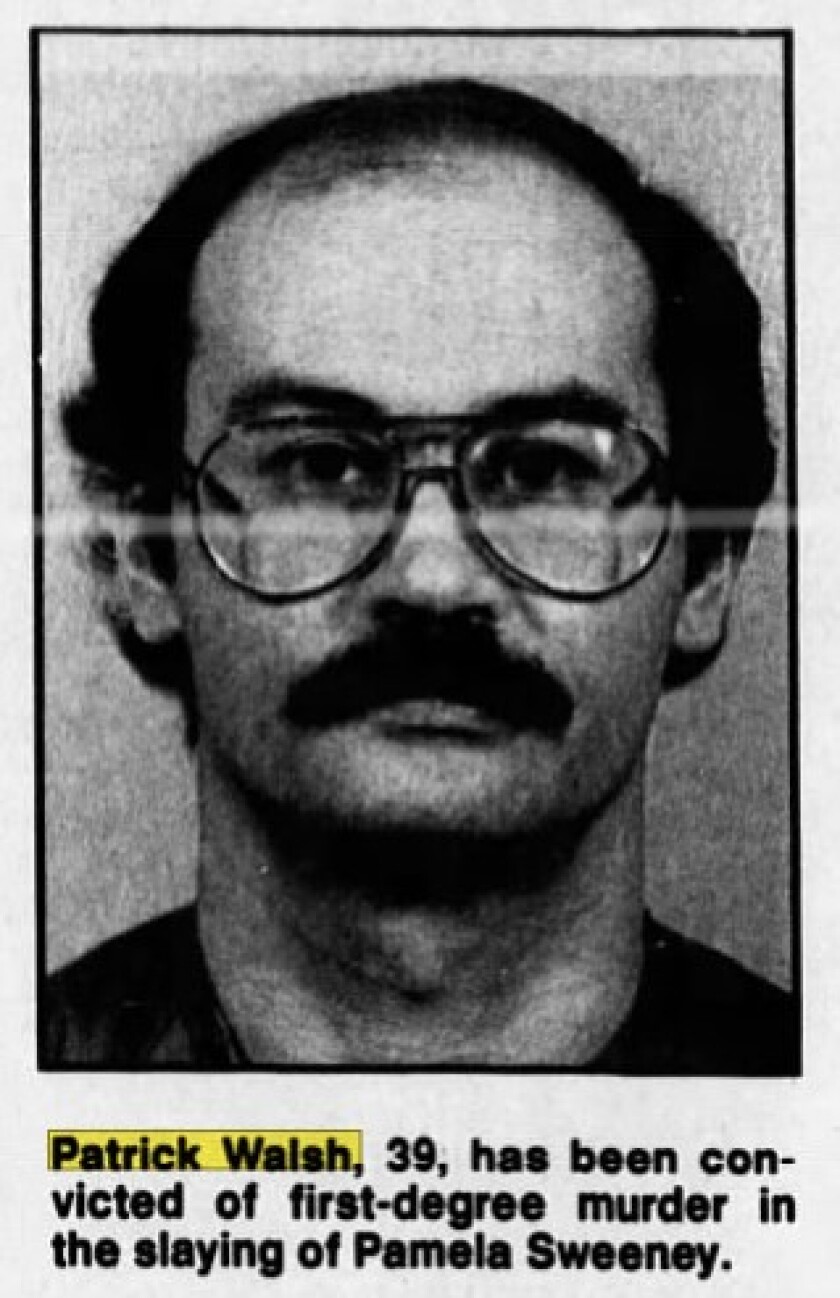

In May 1991, Janet’s husband, Walsh, was charged with the murder of Pamela Sweeney, an Andover, Minnesota, woman. When Walsh’s name was revealed, Kloster “got chills from head to toe,” she said, adding that she immediately told her husband to call the police.

Kloster called attention to the connection between Cindy and Walsh. Detectives working the case, she said, took her information seriously.

Walsh was described as a person of interest in Cindy’s case at that time by police officers including Minneapolis Deputy Chief Ted Paul and Lt. Brad Johnson, as well as the investigative detective Lt. Bernie Bottema, in the Minneapolis Star Tribune and the St. Paul Pioneer Press.

ADVERTISEMENT

An early history of violence

Outwardly, Walsh was friendly, well-dressed, humorous, and made a good impression. Inwardly, the violence erupted with eight violent attacks — mostly against women — by the time he turned 25 years old, according to the Pioneer Press in 1991.

The attacks began in 1966, when Walsh, at 14 years old, stabbed 12-year-old Viola Newman in the spleen, the Pioneer Press reported. After the stabbing, Newman recalled that he asked whether she was OK. She replied yes and he became sympathetic, but eventually left her. After authorities caught up to him, he was placed in the Minnesota Treatment Center at Lino Lakes, and was released in 1968 even after one psychiatrist called him a “dangerous psychopath.”

“The attack on Newman marked the beginning of a revolving-door journey for Walsh through Minnesota’s criminal justice system, mental hospitals and halfway houses,” the Pioneer Press reported.

Six months after his release, he threatened a woman on a Duluth street with a knife. He was sent to Moose Lake State Hospital for more treatment, where he attempted a similar attack on a nurse. Three months after Walsh walked out in 1970, he savagely attacked a 15-year-old boy. While waiting on court action, he committed another near-fatal attack on a woman in Duluth.

While babysitting for a friend, Walsh knocked on a neighbor’s door and asked the occupant, Janice Olker, if he could borrow a can opener, the Pioneer Press wrote. She obliged, but when he returned the tool, he saw she was decorating for Christmas.

Walsh thought decorating was a waste of time, and then stabbed her seven times with a knife, the Pioneer Press reported. As he left, Olker’s roommate returned with her boyfriend, and Walsh handed him the knife.

“I’ve been drinking. I just came over to borrow a can opener and don’t know what came over me,” Walsh reportedly told the couple.

ADVERTISEMENT

Walsh took the stand in his trial, confessing to assaults authorities weren’t aware of, and a jury acquitted him as “mentally ill with homicidal tendencies,” the Pioneer Press reported. Former St. Louis County District Judge Patrick O’Brien committed Walsh to St. Peter Security Hospital, saying he “would not be in a position to injure other persons for a good long while,” but was released in 1977.

“Why would they let him out?” Newman asked reporters in 1991.

A list of mysteries

Newspaper reports at the time painted Walsh’s violent past in detail, and to other mysteries, according to court documents.

Walsh’s time at St. Peter Security Hospital, Minnesota’s top treatment facility for sexual aggressiveness, Timothy Crosby, also a juvenile at the time, and later a in Monticello, Minnesota.

Crosby was later involuntarily committed to the secure Moose Lake Sex Offender Treatment Program facility, where he remains today.

Three years after Walsh was released from St. Peter Security Hospital, Walsh’s live-in girlfriend, Cindy May Brown, told her Kmart supervisor on March 10, 1980, that she was planning on leaving Walsh and the town of Roseville, Minnesota.

ADVERTISEMENT

She was never heard from or seen again.

Four months later, Walsh, who found work with computers at Unisys Corp., told police that she left with friends and headed west, for Unidentified & Missing Persons. At the time, police figured Brown had left of her own free will. when Walsh became a suspect in Sweeney’s murder. Foul play was suspected.

On March 8, 1984, Cindy Gerdes was planning on leaving her employer, Office Interiors, and few people knew she was at home that afternoon as in Texas.

She was intelligent, athletic, frequently went skiing and canoeing with her boyfriend of six years, Ken Hammer, and she was always wary of strangers, family said.

“All the things you said about her are true: she was hardworking, she was very intelligent. She was not a party girl at all, she was very focused on career and family,” Michael Gerdes said in a recent interview. “To let [the murderer] into her apartment? That doesn’t sound like her. I just don’t see Cindy letting him into her apartment.”

“Either he had a key or she let him in,” sister Mary Broberg added.

Cindy was stabbed multiple times and left in a pose of shock for nearly two days before her roommate found her. Multiple suspects were questioned, including Hammer, who was followed by FBI agents before they crossed him off the list, according to the police case file.

ADVERTISEMENT

The police investigation did not uncover how Cindy Gerdes’ killer gained entry into her apartment, and her killing was classified as a “lust murder.” The killer was disorganized, and he did not initially intend on killing her. He took a weapon of opportunity — the missing knife from the butcher’s block — and “commenced with a frenzy attack of the victim,” the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s profile of the killer reported.

Sentenced to life

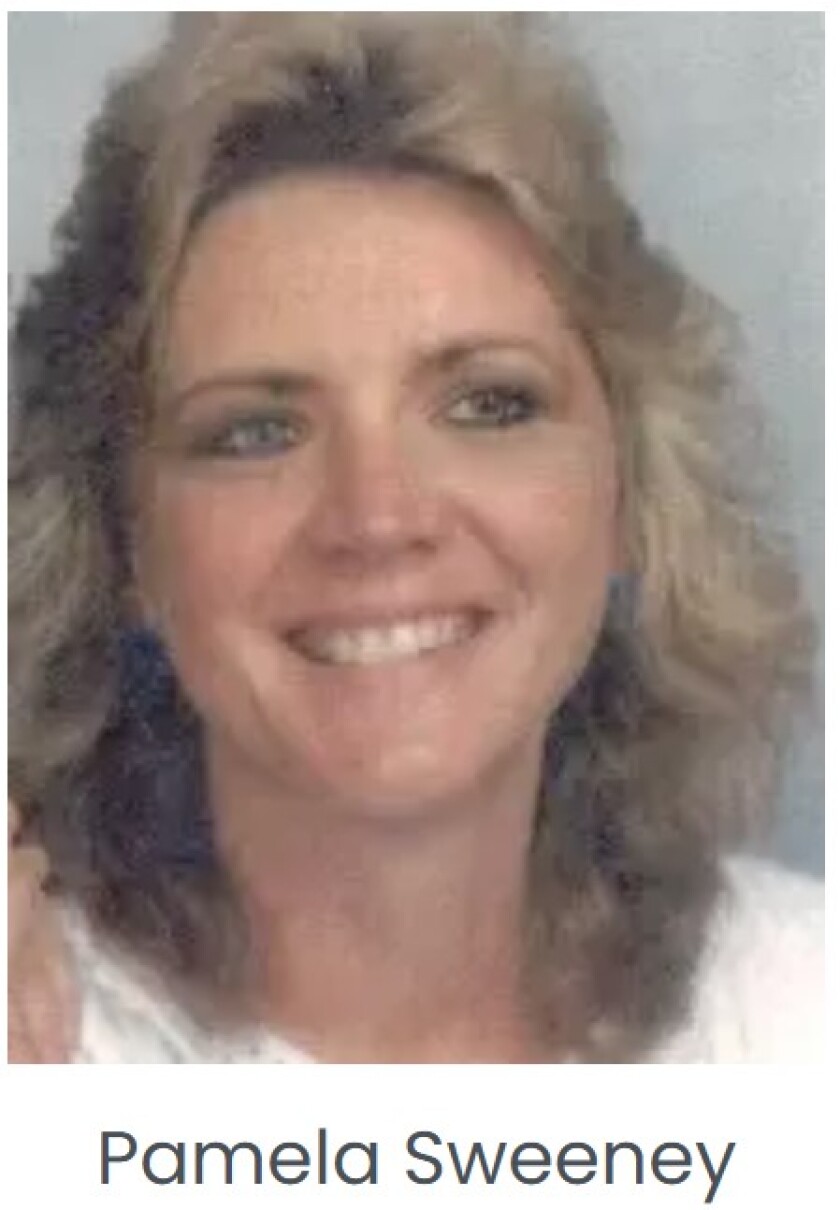

Sometime before May 31, 1991, Walsh began stalking Sweeney, a co-worker at Unisys Corp., where she worked as a secretary, according to the Star Tribune. He mowed her lawn, and shoveled snow from her driveway without being asked. Sweeney refused his advances. He stole her house keys, according to court documents.

Sweeney, who earlier told her fiance to come over no matter the time, was found shot and stabbed to death. The fiance called 911 from a neighbor’s house, telling emergency personnel that a man was still there, the Star Tribune reported.

Heavy rain turned the yard to mud, and Walsh mired his pickup truck. In a panic, he dialed 911, according to court documents.

Police found him inside Sweeney’s kitchen, and although Walsh denied he was the killer, all evidence — including candy wrappers, murder weapons, blood stains and leaves and grasses on his clothes — . Her murder was one of the cases that prompted new anti-stalking laws in Minnesota.

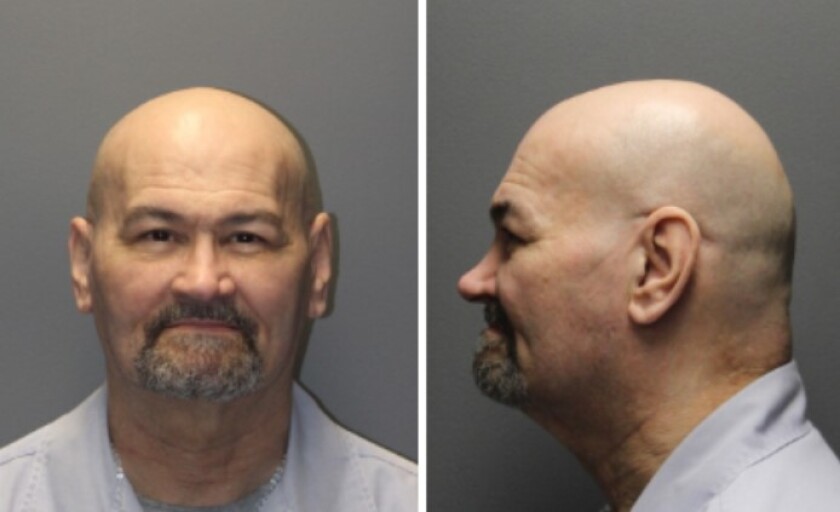

Walsh was sentenced to life imprisonment and is being held at the Minnesota Correctional Facility in Stillwater. Forum News Service reached out to Walsh through the Minnesota Department of Corrections for an interview, which he declined.

Finding forgiveness

During the winter of 1986, two years after Cindy’s murder, Mary Broberg was working at a Teens Encounter Christ conference. During confessional time, she told the priest that her heart had become stone because of the unexplained loss of her sister.

“Really?” the priest asked. “And he pulled out his Bible and said he was reading Scripture right before I came in and it read: ‘God would take out your heart of stone and make it into a heart of flesh,’ ” Broberg told Forum News Service.

Even though she had no idea who the killer was in 1986, Broberg’s eyes teared up. “So I forgave him at that time. And it released me,” she said.

After 40 years, the Gerdes family has found some closure because they believe they know who Cindy’s murderer is.

“Personally, I haven’t forgiven him. I never will,” Michael Gerdes said.

“I don’t feel hatred toward [the murderer] because I know he is a sick person. But I still do think justice should be served. Maybe at this point in [the murderer’s] life, he would be willing to talk,” sister Claudia Gerdes said about Walsh.

“I would ask him to man up and admit it at this point in his life, why not?” Michael said.

They still cling to hope that the case will be solved.

“It would give our family more peace for [the murderer] to admit what he did,” Broberg said.

Mary Kloster remembered Cindy’s open casket funeral in Moorhead.

“In the casket, her nails looked broken. I glanced at her one time in the casket because she didn’t look as beautiful as she really was. But I noticed her fingernails. Until news came out later on, I had no idea how horrific her death was,” said Kloster, who at the time of Cindy’s murder began to wonder about her own safety.

“I would like to see it solved. From 1991 on, I feel like I saw a connection and I thought that even in 2006, they would find some DNA or something to make a connection or not make a connection. Cindy deserves to have justice for her case,” Kloster said.