COMSTOCK, Minn. — Swedish immigrant farmers founded the Clara Lutheran Church in Clay County’s Holy Cross Township in the late 1800s.

Decades later, their descendants decided to merge with their Norwegian-descended neighbors. Both congregations were small and both churches were old, and over time many families had intermingled through marriage, so they combined in the 1960s as Comstock Lutheran Church.

ADVERTISEMENT

Although Clara Lutheran Church is long gone, Clara Lutheran Cemetery remains, surrounded by farm fields on a site northwest of Comstock.

The cemetery has weathered countless blizzards, hail storms and droughts, but now faces a new threat: flooding created by the metro flood diversion, which will operate during severe floods.

The diversion project’s 20-mile earthen embankment and three gated control structures will back up water over an area south of Fargo-Moorhead, upstream on the Red River.

What’s called the upstream mitigation area includes 11 rural cemeteries that face some degree of flooding risk, which diversion officials are working to address in consultation with the owners.

Clara Lutheran Cemetery, located within what will become the pool area, faces the greatest risk.

Engineers calculate that the cemetery will be inundated by four feet of water in a 100-year flood and eight to 10 feet in a 500-year flood.

“It’s probably the cemetery that’s impacted the most,” said Joel Paulsen, the Diversion Authority’s director. “Honestly, many of these cemeteries are pioneer cemeteries.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Officials are working on mitigation plans for the five cemeteries with the greatest impacts.

Initially, congregation members were alarmed at the impact to Clara cemetery.

“We kind of fought it,” said Mark Anderson, a farmer and member of Comstock Lutheran Church’s cemetery committee. “We have a lot of people whose grandparents were buried there and whose parents were buried there.”

The cemetery, with roots in the pioneer era, was declared a historic cemetery by the National Trust.

Once the diversion had all of the needed permits, however, and it became clear that the project was going to be built, the congregation negotiated with the Metro Flood Diversion Authority.

“Sometimes you just have to accept stuff,” Anderson said. “And once it’s going to be, you have to deal with it.”

The process was laborious, involving multiple agencies, including the Diversion Authority, Army Corps of Engineers, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and Minnesota Historical Society.

ADVERTISEMENT

“They all had different ideas on what to do,” Anderson said. “We mixed and matched.”

At first, the Diversion Authority proposed a dike tall enough to protect against a 500-year flood, but church members decided that was too much, he said.

“It was going to make it look like a swimming pool,” Anderson said. “The aesthetic on four feet is very different.”

Plans call not only for wrapping a berm around the cemetery, but also raising two nearby roads. An unoccupied corner of the graveyard will serve as a new sloped entrance “up and over” the dike.

The stately pine trees surrounding Clara cemetery are dead, victims of age and a devastating hail storm a few years back.

New trees and shrubs will be planted once the dike is built.

“They came around on a lot of our suggestions,” Anderson said. “I think it was about the best we could do.”

ADVERTISEMENT

'Tough to be uprooted'

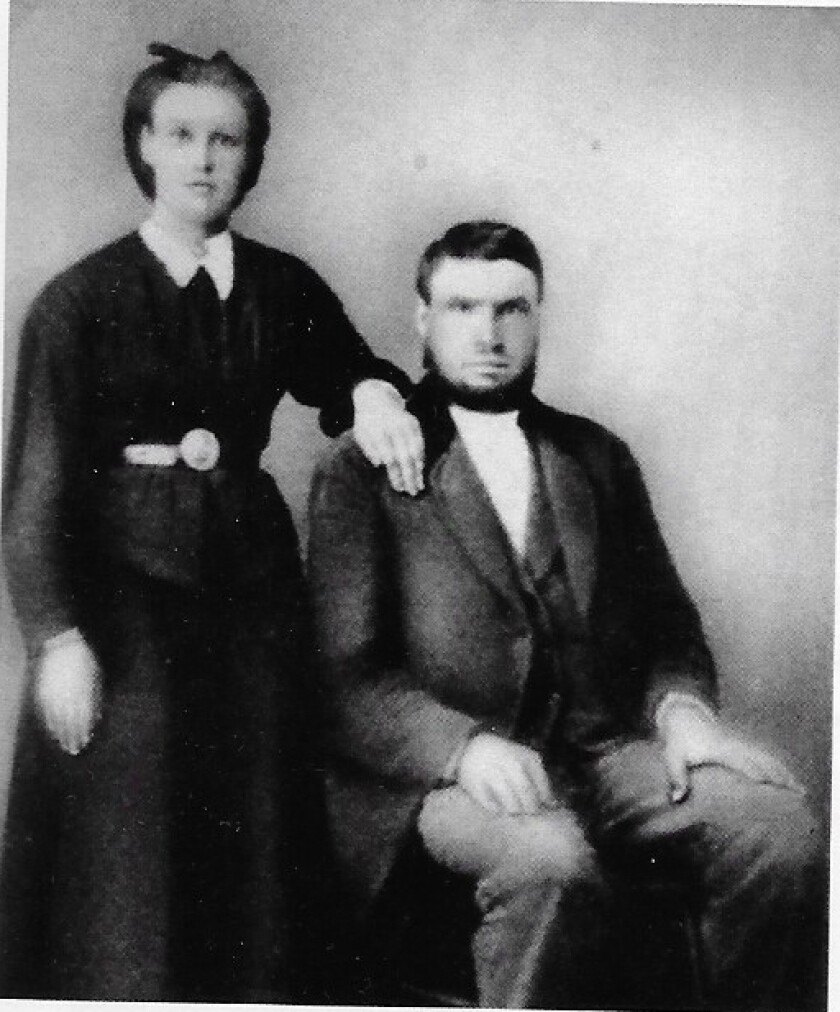

Narve Roen immigrated to the United States from Norway with his parents when he was 2 years old.

His family settled in Wisconsin and young Narve enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War, serving under Gen. William Sherman.

After the war, life took him to southeast Minnesota, then he and his wife, Gor, traveled by oxen-drawn covered wagon to a homestead near Comstock in 1871 to establish a farm.

“It’s been in the family since,” said Rhoda Ueland, Roen’s great-granddaughter and the farm’s current owner.

Both Narve and Gor were immigrants from Hallingdal, Norway. Narve built the first wood-frame house in the area in 1881. Later, their second-oldest son, Stennom, Ueland’s grandfather, built a stately home with a prominent columned, semicircular porch.

The farm includes a small Roen family cemetery, with the graves of children, the smallest of the cemeteries that are at some risk from the diversion.

The diversion means the family must abandon the farm and cemetery. Structures will be demolished, although Ueland wants to move one of the farmhouses.

ADVERTISEMENT

Ueland and her father placed markers on the previously unmarked graves in the 1980s, all ancestors who died very young: Ida Myrtle Roen, age 2; Ingvald Roen, age 5; and Ida Roen, age 18.

“It’s kind of tough to be uprooted when your roots go back so deep,” Ueland said.

As negotiations continue over the sale, Ueland’s family is dealing with the loss of their ancestral farm.

“Pulling up family roots so deeply rooted since 1871 has become a nightmare,” she said, adding that her father and grandfather instilled pride in the family’s pioneer heritage. “Many neighbors and friends are also going through this process of grieving the uprooting of their own heritage.”

Safeguarding 'sacred places'

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which started investigating the impacted cemeteries in the early 2010s, compiled an extensive survey and report to document their histories.

“Cemeteries are sacred places and they’re associated with communities for all the reasons you would expect,” said Susan Malin-Boyce, an archaeologist for the Corps. “It ties people to the place. It’s a sense of belonging and ancestry to a place.”

When operating, which engineers estimate will be about once every 20 years, the flood project will cover some of the cemeteries with water.

ADVERTISEMENT

“No cemeteries are being removed and there will be no disinterments,” Malin-Boyce said.

Diversion officials and their representatives will continue to work with landowners and cemetery owners to mitigate issues caused by the flood project.

The Diversion Authority has an obligation to protect the cemeteries and, following a flood, to clear debris, said Jodi Smith, director of lands and compliance. Negotiations continue with many of the cemetery owners.

“We don’t have signed agreements with all the cemeteries yet,” she said.

In some cases, if needed, headstones will be elevated and re-seated, Paulsen said.

“We want to address that we’re committed to mitigating any impacts to any cemeteries,” he said.