PARK RAPIDS — Park Rapids author Art Burns shared memories of his boyhood on the Ponsford Prairie, his studies at Park Rapids High �������� and his career in U.S. Army intelligence at the Hubbard County Historical Society’s program on Monday, July 29.

Burns, 93, was supported by his wife Mary and daughters Lori Sullivan and Jackie Skaurud. The couple also has a son, Tom. Some of Burns' recollections were drawn from his memoir, “Not for Naught: Humble Soldier, Remarkable Life".

ADVERTISEMENT

Was he the Lindbergh baby?

Arthur Lee Burns was born in 1930 in a farmhouse near Boyceville, Wis., where his parents were sharecroppers. This meant they operated a farm and split the profits with the owner. As the Great Depression got underway, the owners’ sons lost their jobs and moved home to work the farm, putting Edward and Dora Burns out of work.

On their way to stay on Ed’s parents’ farm in the Osage area – the site of the Lions’ park today – the family was eating in a diner in Little Falls, Minn., hometown of Charles Lindbergh. At that time, everyone was on the lookout for the kidnapped Lindbergh baby, who had the same size,weight and blond curls as little Art.

The family story, according to Burns, is that the diner suddenly emptied out and FBI agents rushed in, taking the boy from his parents so they could compare him to the description of the blue-eyed Lindbergh baby. Only when they jostled him and he opened his eyes did they see that his eyes were brown, not blue.

Art recalled early childhood experiences on his grandparents’ farm, staying cool in their ice house and watching the steam threshing machine at work. In the fall of 1934, he said, his parents got their own firm, first renting it from a local doctor and later buying it from the doctor’s son. He admitted having to visit the same doctor when, for some reason, he stuffed beans into his ears and nose.

Burns told of attending a one-room, grades 1-8 country school, where he loved geography so much that he borrowed the teacher’s book over the summer and all but memorized it. “It probably was a good preparation, because I traveled the world later on,” he said.

Heading into town

In those days, he said, it was a treat to go into Park Rapids on Saturday night. “All the stores stayed open,” he said. “The lights were on, and there were two theaters, three ice cream parlors, two bait stores, two banks – just on Main Street alone – and five grocery stores that I remember.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Burns recalled how children would gather to see the steam-engine trains go through the center of town, and the engineer would scare them with a blast of steam. He painted a word-picture of coal bins, grain elevators and sidings where merchandise was unloaded.

“Practically anything big came in by train,” he said. “In fact, my grandfather sent up all of his horses from Lac qui Parle. He had four Percherons, and some of their furniture came by train.

“That was the exciting part of town, and the other part was the bridge that led over to the big sawmill.”

All this activity took place next to the park, where there was a band shell where the community band would play music on some Saturdays and Sundays, as well as a World War I cannon that tragically blew the hands off a man who was loading it.

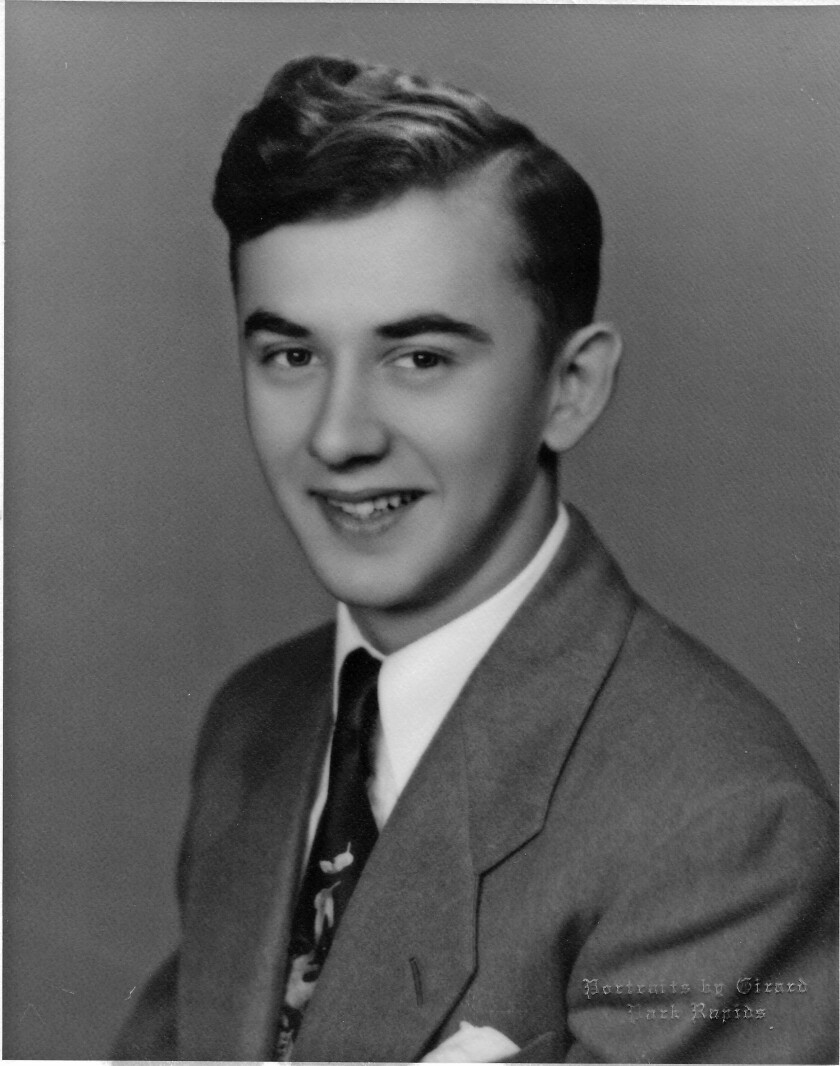

As a member of the Park Rapids Class of 1949, Burns was one of the first students to go to the “new” high school, built after the previous school burned down. He particularly loved the chemistry lab and the school library, which he said was even bigger than the town’s Carnegie Library.

Burns said he had the hardest time in English class, mastering grammar only with a lot of help from teachers and tutors. Ironically, when tested by the Army, he scored the highest in language.

ADVERTISEMENT

Romance of military service

In the winter of 1939, Burns recalled, there was an exhibition baseball game between Osage and Park Rapids, where he heard the first whispers of a coming war.

His father Ed was drafted, but his draft was deferred because of his large family (three kids) and the importance of farmers to the war production footing.

Burns discussed how everything was rationed during the war, with most folks’ travel restricted to 200 miles without special permission and a gas supplement. Meanwhile, he said, farm families were allowed to eat one cow and one pig per year, with the rest going to the soldiers – a restriction enforced by local veterinarians while livestock were reported on farmers’ tax returns.

Art’s older brother Fernale left high school early to start a career in the Army, serving in World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

Burns talked about local families hanging star flags in their windows – a white star for each child still serving in the armed forces, and a gold star for those who were killed. He tied this in with the Minnesota National Guard, many of whose members either died in the Philippines or suffered through the Bataan Death March.

During the war, Burns said, no lights were lit in town, and a popular song was “When the Lights Go On Again.” The celebration when the war ended and all the lights came on again was “magical,” he said, admitting he was impressed by all the guns being fired in the air.

“I guess the idolization of the armed forces of that time impressed both my brother and I,” he said. “It still does.”

ADVERTISEMENT

‘How would you like to be a spy?’

Burns himself joined the Army in 1948, starting with a National Guard training camp before heading to Fort Riley, Kansas in December.

“The wars were over, and they didn’t really care if you stayed in or not,” he said. “And so, basic training had gone from four weeks to four months.”

As basic training wound down, he underwent a battery of tests, hoping to qualify for airborne duty. Instead, he was invited into a room with seven other guys and told, “How would you like to be a spy?” All seven, Burns included, were on their way to careers in army intelligence.

“The FBI started going around Park Rapids and checking out who Arthur Burns was,” he said. “He got to Mert Engel, and I’d worked for him, and he verified, and the police couldn’t find me on the blotter. So, I finally got my interim clearance, and all seven of us made it.”

Burns ran through a long list of his assignments during an Army career that spanned the Korean and Vietnam war eras, including a stint scanning Russian-language materials for a memorized list of keywords, studying the “Russian problem” in Japan, preparing battle plans in Germany and Washington, D.C., serving a combat command in Vietnam and teaching trainees at Fort Devens in Massachusetts.

Meanwhile, he and Mary got married and raised three kids, who experienced a far different childhood from his own – moving from duty station to duty station, learning multiple languages and cultures and cherishing Park Rapids as their “rock” that they could always return to.

ADVERTISEMENT

After leaving the Army, Burns served 11 years as a veterans service officer in Park Rapids before retiring. “Since then, we’ve traveled considerably,” he said. “We’ve been to many, many countries and had some wonderful years.

“I was very privileged to be able to have the occupation as a soldier. That’s what I wanted to be, from World War II. I was privileged and very happy with what happened in my life. I feel I did the best I can for my country, my God and my people, my family, and I’m glad I’m back and alive.”