Editor's note: If you or a loved one is in crisis, you can call the at 1-800-273-8255 ( 1-800-273-TALK) . Or call the Native Youth Crisis Hotline at 1-877-209-1266.

FARGO — On a grassy landscape along a sidewalk in Lindenwood Park at the edge of Fargo, Grace Poitra and Robbie Lass knelt to pray.

ADVERTISEMENT

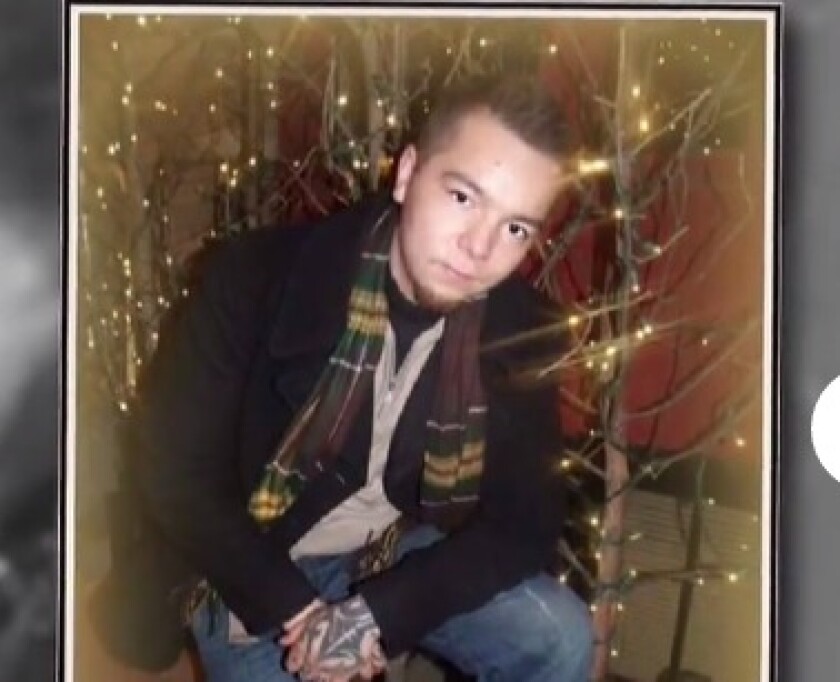

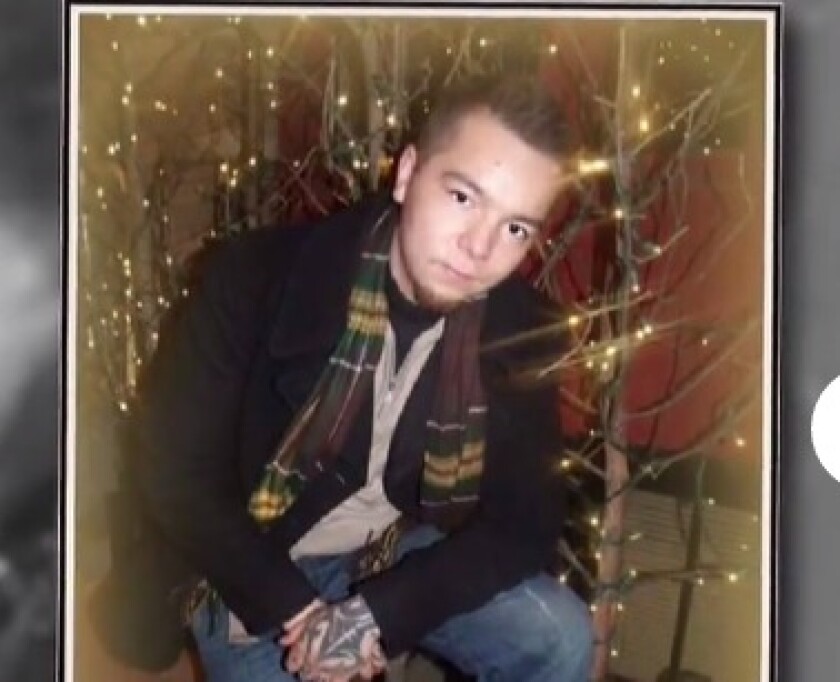

Lass, from the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, and Poitra, from the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota, had met four years earlier, and started dating just a few days after they’d first met. Now they had a son together, Joey Little Bear.

During their relationship, Lindenwood Park had become a go-to for whenever Lass was going through a tough time. He struggled with substance abuse and depression, issues that Poitra thinks were a result of childhood traumas, like being attacked by a dog as a toddler, losing his grandmother who took care of him as a preteen, and spending time in juvenile detention.

Moments after the two had been praying, Lass saw what he thought were doves flying and said it was a sign.

“Those are pigeons, Robbie,” Poitra said.

She laughed as she recalled the memory. Those “dorky moments” are what she loved about him.

But Poitra didn’t know that as they strolled along the serpentine path through Lindenwood, this would be their last walk together there. About a year later, on June 27, 2016, Lass died by suicide in that park.

Poitra said she didn’t go back to the park for a while. Then it became the only place she could go to remember him.

ADVERTISEMENT

Lindenwood Park has often been the site of Fargo-Moorhead’s annual suicide awareness walk each September. The walk aims to shed light on the issue of suicide, which disproportionately affects indigenous people, like Lass.

Federal data show a bleak picture for the suicide rate in indigenous communities — the American Indian and Alaska Native population is to die by suicide than racial groups with the lowest rates. But prevention efforts among tribal nations in the region are growing and working to educate youth and adults about risk factors and signs. Prevention coordinators — fighting the effects of historical trauma and marginalization — said they’ve already seen some levels of success. But quantifying that success is difficult.

Tribal-specific numbers are hard to come by in North Dakota and Minnesota. Pamela End of Horn, the national suicide prevention consultant at Indian Health Service and a member of the Oglala Lakota Tribe of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, said she rarely releases data at the tribal level for privacy reasons. That’s because individual tribes have relatively small populations, and suicide is such a rare event for individual tribes that one could easily trace a single case back to the person who died.

In Minnesota, where Robbie Lass grew up, there were 98 suicides, a rate of 23.2 per 100,000 people, among the American Indian population from 2013 to 2017. That's a 61% increase from the four years prior. The suicide rate among the white population increased 14% over that same time period, from 11.8 per 100,000 to 13.4 per 100,000.

The American Indian suicide rate in North Dakota is trending upward as well, according to the . Though the year-to-year rate fluctuates, the average suicide rate among the state's American Indian population from 2014 through 2018 was 35.5 per 100,000. That compares with the average rate of 20.2 per 100,000 among the overall state population.

Suicide data for the Indigenous population remains limited, though, said Gretchen Dobervich, a policy project manager at the American Indian Public Health Resource Center at North Dakota State University. She said tribes have different methods of recording deaths by suicide. Another issue is sometimes the cause of death isn’t properly marked on a death certificate. She added that suicide attempts are also difficult to track unless a person seeks medical care.

“There’s just a lot of work that needs to be done on the data gap,” Dobervich said.

ADVERTISEMENT

The American Indian Public Health Resource Center is working to collect better data for the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nation in western North Dakota. The center partnered with the Elbowoods Memorial Health Center to evaluate their suicide intervention program and to gather baseline rates of attempts and completed suicides, to “get a full picture of what’s going on,” said Vanessa Tibbitts, a program director at the center and a member of the Oglala Lakota Tribe.

Behind the high rates of suicide in Indian Country is often what’s known as historical trauma, said Dr. Donald Warne, the director of Indians into Medicine at the University of North Dakota. Such trauma — stemming from massacres like the one at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, and government policies such as decades of forced assimilation through boarding schools — is passed down through generations.

“There’s a lot of childhood trauma and intergenerational trauma,” Warne said. “Children who have trauma grow up and have children with trauma.”

Poverty, unemployment, isolation and substance abuse — all risk factors that can lead to suicide — stem from those traumas, Dobervich said.

“They’re living the product of that trauma,” she said. “It’s almost like a double whammy in that you’re experiencing the trauma, and plus your everyday life is the result of that trauma.”

Survival buddies

Robbie Lass grew up just outside of the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota. When he was a toddler, a dog attacked him, scarring his face. Later on, he went to live with his grandmother, who died of cancer when he was 12. Then he went into the foster care system and spent time in juvenile detention.

As an adult, he received a settlement for the dog attack, and he used some of the money to buy Poitra a promise ring. They later had to sell the ring at a pawnshop.

ADVERTISEMENT

Someday, Poitra said, she would have married him if he were still alive.

The two met through mutual friends at a party. Both were into drawing tattoos. Poitra is more reserved. Lass was “off-the-wall.” He’d do anything to make someone laugh, she remembers.

He knew right away they would be something special, but it took her a little longer to realize it.

They eventually became survival buddies, often couch-hopping or selling their possessions to get by. Then they decided they wanted to start a family together, so they had Joey, who’s now 5 years old.

Being a dad was hard for him, though, Grace said. He was struggling with depression and substance abuse, and he’d attempted suicide at least eight times before ultimately taking his life.

Since Lass’ death, Poitra said she wonders if he thought about Joey before he died, and how he’d have to grow up without a father. She paused. “Eventually I’m going to have to tell him what happened.”

Lass’ mother and sister couldn’t be reached for comment for this story.

ADVERTISEMENT

Monique Runnels, the director of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s wellness program, said prior to the traumas of boarding schools and attempted cultural genocide, “there wasn’t that addiction; there wasn’t that abuse. There was always thinking of the future and of future generations.”

Among indigenous populations, youth suicide is "strikingly higher" than the overall U.S. population, according to . For indigenous people, the suicide rate decreases with age, compared with the general U.S. population where the rate increases with age.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, which straddles the Dakotas and has about 15,000 members, hasn’t seen a youth suicide in more than four years. “That’s pretty amazing,” Runnels said.

Runnels has worked as the tribe’s wellness program director for four years. Her suicide prevention efforts can be summed up as “collaboration.” The wellness program works with several different groups — law enforcement, the youth council, substance abuse treatment — in its preventative efforts because, she said, “all of it is suicide prevention.”

“We’re working together to solve those underlying issues that would lead to alcoholism to suicide or drug abuse or anything else,” she said.

As for the reservation’s adult population, Runnels, a Standing Rock citizen, said suicides are more persistent, likely as a result of substance addiction.

But, her message about the problem was a positive one: “Yes, a lot of our people may think about suicide, but a majority of our people do not, and a majority get the help they need.”

ADVERTISEMENT

At the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Tribe of the Lake Traverse Reservation, which is mostly in South Dakota but pokes into North Dakota, tribal citizens can get help through a 24/7 crisis line.

Dr. Gail Mason, a member of Canada’s First Nations, is the tribe’s director for behavioral health and helped start the call center. The crisis line works across agencies, with law enforcement and social services, to set up next-day appointments with callers, do police wellness checks and follow up with patients. Mason said in the past three years since the crisis line’s inception, the call center has received and made about 2,000 to 3,000 calls a year.

The call center started after a survey of several hundred tribal members revealed about 95% of them said a crisis line would help overall public health. Mason, who has a doctorate in clinical psychology and a post-doctorate in psychopharmacology, said it’s helped connect people in rural areas to services. She added that the top risk factor for the population is lack of connectedness as a result of the rural nature of reservations in North and South Dakota. “We’re terribly isolated,” she said.

Isolation doesn’t only apply to rural indigenous populations. Lolan Lauvao, the suicide prevention coordinator for the Phoenix Indian Center in Arizona, said indigenous people who leave their tribe and reservation often struggle with loneliness and disconnectedness.

“It’s a great culture shock for someone moving from reservation to the city,” said Lauvao, who is a Native Hawaiian of the Samoan Tribe.

The Phoenix Indian Center has served as a gathering place for indigenous people since 1947, Lauvao said. In his role as the suicide prevention coordinator, Lauvao trains everyone from children to parents on how to talk about suicide in an effort to erase the stigma around it.

“If we can just be open and normalize it, and people are more comfortable with it, imagine how many lives you can save,” he said. “Just because we don’t talk about it, doesn’t mean we don’t think about it.”

'It's consistency'

While Lass was alive, Poitra said she struggled to talk to him about his previous suicide attempts, and she said they didn’t make a plan for when he had suicidal thoughts. “You don’t want to bring it up when you’re in a good mood because it’ll just ruin the mood,” she said. “And then when you’re in a bad mood, it’s just going to intensify everything.”

Since his death, she said talking about him reassures her he was actually there. “It helps me remember that he was a real person, you know? Because people like to forget.”

She said it gets a little easier, though, to deal with losing him. But “sometimes it’s really hard,” she said through tears. “I still miss him every day.”

Like Poitra, Claudette McLeod is a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in northern North Dakota. McLeod is the tribe’s outreach director, and she has been training her tribe on suicide prevention for two decades, focusing especially on the youth population. She started the prevention program alone in the basement of her house. Now 20 years later she has six full-time employees, federal funding for the program, annual events such as a suicide awareness walk, and relationships with the hundreds of students she’s helped.

Her program uses the “Sources of Strength” curriculum to educate and train young people on bullying and suicide prevention. Over the years, she’s trained 500 kids in the community. Her program also hosts weekly “talking circles” where kids eat, then sit in a circle and share their names, how their weeks are going, and one generous act they did.

In building youth up, McLeod even goes to school sporting events to watch her students play.

“It’s consistency,” she said. “A lot of kids in Indian Country have been let down already. We need to build these kids up and not let them down anymore.”

Poitra said she eventually wants to start a nonprofit group to help young indigenous boys who face trauma, as Lass once did.

She’s hoping that by helping young kids on the reservation, it will allow something positive to come out of his death.

“I’ve got to try something,” she said. “I can’t just stay quiet about it.”