CLONTARF, Minn. — At least 14 Indigenous students who attended the St. Paul Diocese Industrial حلحلآ» of Clontarf in the late 1800s are buried in two plots in the St. Malachy Cemetery in Clontarf. A review of an incomplete list of school documents suggests there were more than 14 student deaths at the school near Benson.

A memorial erected during the town’s 1978 centennial describes the people buried there as “Sioux and Chippewa Indian youths†who died while attending the Clontarf Industrial حلحلآ» between 1878 and 1898.

ADVERTISEMENT

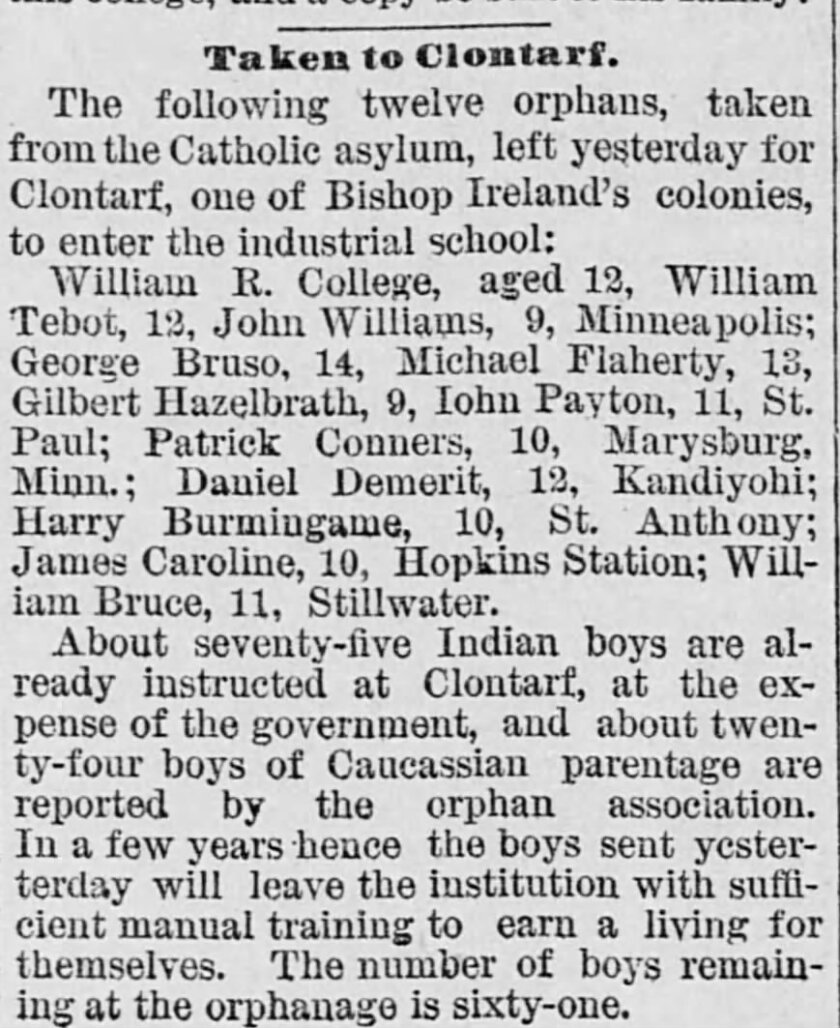

The school, located in Clontarf from 1877 to 1898, taught a mix of Indigenous students from various tribes through a contract with the federal government and also white orphans from Minnesota.

According to Swift County death records, all those listed on the memorial died between 1883 and 1893, mostly from tuberculosis, commonly referred to as consumption at the time.

Those named on the memorial have “Dakota†as their birthplace on county death records. Their ages range from 9 to 22 and are all males.

An incomplete list of quarterly reports from the school, which are part of a collection of documents maintained at the University of Minnesota - Morris , lists at least 18 deaths at the school.

A March 1886 quarterly report lists Isreal Langer, 10, of the Chippewa tribe, and Nicholas Lanninyan Nayi, 14, of the Sioux tribe, as having died that quarter. They are not listed on the memorial.

ADVERTISEMENT

A June 1889 quarterly reports lists seven deaths that quarter but only Benedict Ahami, 18, whose tribe is listed as Sioux, is on the memorial. The names of the other students who died at the school that quarter are currently unknown.

A 1978 states the students listed on the memorial died during epidemics at the school.

The article also mentions that the school had 108 Indigenous children in 1886 from the Standing Rock reservation, Devil’s Lake (now Spirit Lake) reservation, Pembina Mountain and Turtle Mountain reservations and the White Earth reservation.

The dates of death for those listed on the memorial do not match up with the incomplete quarterly reports the West Central Tribune reviewed, suggesting more than 18 students died during the more than 20 years the school was open.

Quarterly reports for the St. Paul Industrial Boarding حلحلآ» in Clontarf

The Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis has a collection of documents from the school, but they are not digitized and the West Central Tribune has not been allowed to view them.

The Archdiocese did not respond to a request for comment about student deaths or the church running of the school.

ADVERTISEMENT

Clontarf city officials also declined to comment.

The Rev. Gary Mills, director of the Swift County Historical Society and Museum , said he would guess the town erected the memorial in 1978 to document history but he isn't completely sure of the reason and historical records are unclear.

Mills, who grew up around Benson, a town about six miles south of Clontarf, and served as a Lutheran minister for more than 35 years in New York, said it's necessary to find out what exactly happened at boarding schools where Indigenous people were sent.

"We whitewash history and I think it's necessary (to find out what happened) because these are wrongs that, somehow, at least need to be stated," Mills, who has a doctorate in theology from the University of Chicago, said. "People want to right the wrong and that's one issue, but at least we need to recognize and publicly state what the wrong is so people know the truth of the history. "

Mills said he supports working with Indigenous groups in the search for the truth.

"I think it's absolutely necessary and I think we need to be supporting more of that," he said.

That search for the truth can be labor-intensive; documents related to where these Indigenous youth went and what happened to them aren't often held by the tribes themselves and can be scattered throughout various governmental and private institutions.

ADVERTISEMENT

"There's that barrier to access, which is a barrier to truth-finding, which is a barrier to truth-telling and the reconciliation process," Jaime Arsenault, archives manager and tribal historic preservation officer for the White Earth Reservation in northern Minnesota, said. “I think that before we get to this period of reconciliation and before we get to that period of truth-telling, that there is this stage of truth-finding and it has to be done in a way that is led by Native nations so that Indigenous communities aren't further exploited but rather retain their autonomy and self-determination to make these choices for themselves."

Arsenault, who is also the designated repatriation representative for the White Earth band, said she is in the process of working with various colleges in Minnesota to access archival records to find out more about these schools and the impact they had on Indigenous people. The Sisters of the Order of Saint Benedict in St. Joseph, Minnesota, have been particularly helpful and committed to seeing this process through, according to Arsenault.

"A lot of tribal nations have been aware of the impact of residential schools, and that includes the cemeteries; they've long known those stories that are hard to hear," she said. "But people outside the tribal nations don't necessarily have that same knowledge. This history is not taught in the school systems. Now we're getting to this place where many people are starting to hear these stories for the first time. Some institutions are beginning to seek out ways they can support truth-telling and reconciliation efforts and that's good. My hope is that we can collectively keep this momentum going because this is heavy work and it will take time considerable to do it well."

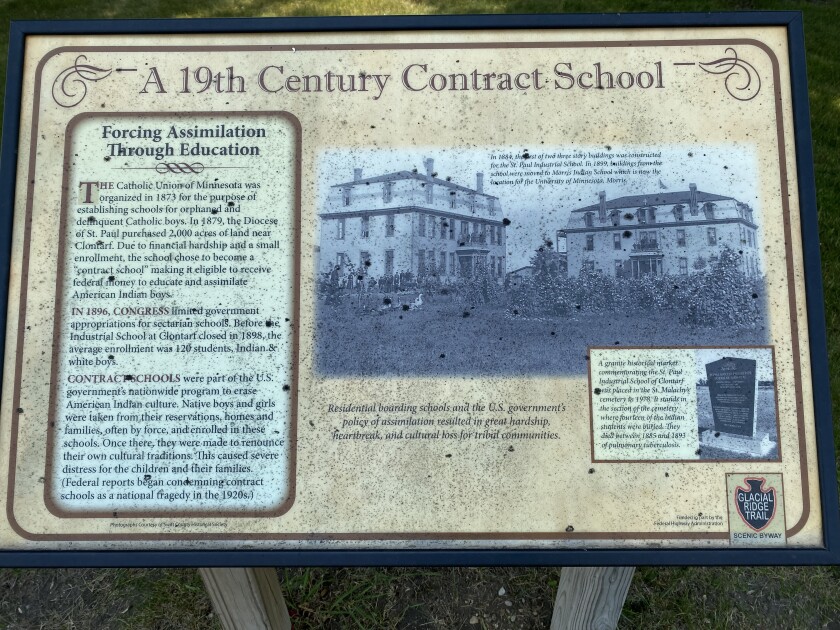

The town also has a plaque next to their post office calling contract schools, like the one in Clontarf, a nationwide program to erase American Indian culture.

The Department of the Interior announced earlier this year that the department will conduct a comprehensive review of federal boarding schools. The school in Clontarf was operated by the federal government between 1897 and 1898.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The Interior Department will address the inter-generational impact of Indian boarding schools to shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past, no matter how hard it will be,†. “I know that this process will be long and difficult. I know that this process will be painful. It won’t undo the heartbreak and loss we feel. But only by acknowledging the past can we work toward a future that we’re all proud to embrace.â€

The department did not respond to a request for comment about whether the Clontarf school will be part of that review.

Besides the White Earth Reservation, no other tribes the West Central Tribune contacted responded to a request for comment.

A in The Saint Paul Globe about the school’s superintendent and St. Malachy pastor Father Anatole Oster mentions he visited the Sisseton tribe and “other Sioux camps for the purpose of securing boys for the school," during his time at the school. Oster was later appointed as the Vicar General of the St. Paul Diocese.

There are multiple news reports at the time of Indigenous pupils running away from the school.

"They were just trying to get away and get back to where they felt they belonged instead of being thrust into a school that their parents never wanted them to go," local Clontarf historian Anne Schirmer said.

Schirmer, who grew up in Clontarf Township, said that while the school tried to do the right thing as far as educating orphaned children and teaching them a trade, taking Indigenous youth from the reservations "was not the right thing to do."

ADVERTISEMENT

by on Scribd

What was the Clontarf Industrial حلحلآ»?

The school, founded in 1874 as the Catholic Industrial حلحلآ» just outside of St. Paul, was moved to Clontarf in 1877 as part of Bishop John Ireland’s desire to teach the children of white colonists in his western Minnesota Catholic colonies, according to the 1956 paper " ," by James P. Shannon.

The school was located about a mile northwest of the 1978 memorial in a place that is now private property.

According to Shannon, not enough colonists' children attended the school, so in 1884 Ireland secured a contract with the U.S. government to teach and board Indigenous children for $100 per child. The school had an average enrollment of 130 children a year.

The students that attended were a mix of white Minnesotan orphans and Indigenous boys. They were taught basic schooling, carpentry, blacksmithing and farming.

The school would later receive $150 per student, according to a February 1889 article from the New Ulm Review.

In 1892, Congress cut funding for residential schools outside of reservations and the school once again faced financial difficulties.

The school was sold to the U.S. government by Bishop Ireland in March 1897 for $10,300, according to an .

A letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs from Indian Affairs Supervisor WM. M. Moss recommended the government not purchase the school, calling the school’s inventory closer to a large stock or dairy farm than a school.

“In fact, there is nothing suggestive of an Indian حلحلآ» to my mind but the 'main school building,' and that only on the outside — the inside being especially repulsive in detail,†he wrote.

The school was operated for a short time as a non-reservation school by the federal government and later consolidated in June 30, 1898, with an Indigenous industrial school for girls in Morris. The distance between the two locations is about 19 miles, so they were both likely drawing students from the same region.

by on Scribd