MORRIS, Minn. — If Minnesota wants to be a leader in the nation or world in the production and utilization of green ammonia, the time is now, according to policy, energy and agriculture leaders at a Green Ammonia Summit on Tuesday, Dec. 10, in Morris.

The Summit was hosted by the Minnesota Farmers Union and included panels of speakers overwhelmingly aware of the risks of trying to develop green ammonia in the state, yet consistently optimistic about why it can work and should happen here.

ADVERTISEMENT

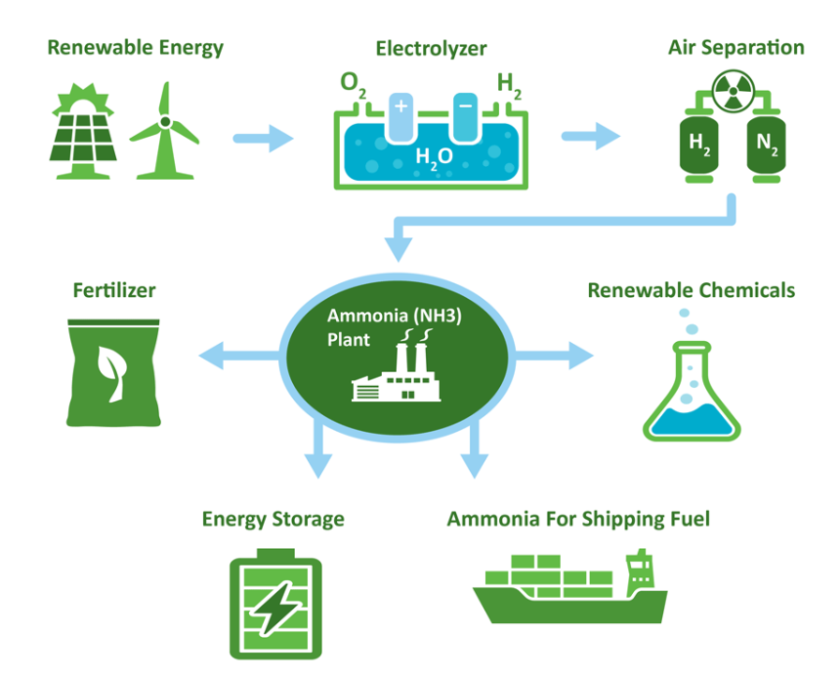

More than a hundred attendees learned about how to make ammonia green. It involves using renewable energy like wind and solar to produce ammonia, instead of fossil fuels, in an attempt to lower carbon emissions.

The University of Morris knows all about that, as and wind to create the most renewable electricity per student in America. That’s something Mike Reese, green ammonia research lead of the University of Morris, is proud of as he promotes renewable hydrogen and ammonia production.

The difficulties in developing green ammonia are plentiful, including high costs of infrastructure, extended permitting processes, and getting buy-in from consumers about what exactly this is and can be used for.

Reasons for trying to build sustainable fertilizer production in the state are also many, according to the host of panel speakers. Building and keeping wealth local as opposed to in other countries is just one.

“Green ammonia is about developing community wealth, I mean having good schools, good hospitals, good social services and all those things that thriving communities have,” Reese said. “And it’s an opportunity for farmers to provide increased profitability by owning part of the supply chain.”

Over time, Reese explained that producing green ammonia for use as a fertilizer will be cheaper than producing it using fossil fuels. He illustrated this by showing the volatility of natural gas prices over decades. It’s one of many costs that grain producers cannot prepare for. He suggested green ammonia and urea would be a more consistent cost. Policy that supports green ammonia production is key, though.

“It’s going to happen," Reese said. "There will be green ammonia. In my opinion, it’s inevitable. I think the real question today is, who is it going to happen with? Is it going to happen with Minnesota farmers and co-ops having ownership in it, or is it going to happen with the same structure that we’ve had?”

ADVERTISEMENT

As a supporter of the cooperative model, Anne Schwagerl, Minnesota Farmers Union vice president, said that’s a way to keep money local.

“We’re looking at things like green ammonia to solve several problems facing farm country. Creating a diversified, farmer owner, resilient, distributed source of our fertilizer,” Schwagerl said. “Because right now, we know that our fertilizer supplies are very concentrated by only a few companies that make them.”

Schwagerl stated that Minnesota farmers spend between $500 million and $1 billion a year on fertilizer, mainly sourced from the Gulf Coast and made from fossil fuels. That money leaves the state. That’s all the more impactful in a year when the corn that the fertilizer is used for might not even be worth the cost of inputs.

“If we keep some of that money in our rural economy, it could be really transformative for us,” she said. “I feel like this is the right time, the right place and the right people in this room to be having this conversation.”

Those people in the room included big ag players like CHS and General Mills; policy leaders like Minnesota Department of Ag Commissioner Thom Petersen and Pete Wyckoff, deputy commissioner of the Department of Commerce; and research experts like Jen King, a research engineer with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

King captivated the audience when she spoke about why Minnesota was the place to develop green ammonia.

“There is enormous potential here in Minnesota,” she said. “It is not just limited to ammonia, and that is actually why it makes it even a better place to go after industrial decarbonization, go after the hydrogen economy because there are multiple applications that exist here.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory analyzed the U.S. to see where it made the most sense to build this green industry, and Minnesota was a winner. The state’s natural resources, embedded infrastructure and existing partners, coupled with low-cost energy, were keys.

“It’s cost-effective to do this in Minnesota,” King said.

What’s making this cost-effective now is the Inflation Reduction Act. While King explained that the IRA funds can be used as long as construction is started prior to 2032, several speakers brought up the unknowns about those IRA funds and other tax credits as the new administration takes over in January.

Ariel Kagan, director of climate and working lands for Minnesota Farmers Union, said it’s imperative that those supporting the green ammonia movement promote its importance and the importance of tax credits to government leadership. She was empowered by the fact that this initiative had bipartisan support working to move it forward in rural Minnesota.

From the perspective of a farmer, building a local supply of fertilizer in rural America would be a gift to the next generation of farmers trying to make ends meet.

Doug Albin, a Clarkfield farmer and board member on the Minnesota Corn Growers Association, is looking for ways to strengthen farming today and in the future.

“What keeps me up at night and what worries a lot of farmers is not necessarily the price of some of our inputs, it’s the availability of it and being held hostage and not being able to get it in a timely fashion,” Albin said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Having the sort of assurance that locally produced ammonia seems to offer, especially when done by a local cooperative, would be a big boost to rural communities and the next generation.

“We could actually keep that money in the community, and it would help with the churches, the schools, businesses. Give an opportunity for our kids to come back to participate in the life that they want to rather than moving to a city or West Coast, East Coast, wherever,” he said.

He said the idea of farmers having to worry about carbon credits and carbon intensity is not something he used to have to think about, but he understands its importance to the future of farming.

“Farmers are always looking for the next, not challenge, but the next opportunity,” Albin said. “And so, this may well be it.”